If you spend as much time online, reading news, etc. as I do to find juicy (relatively) tidbits for The Smokey Wire, you’ll notice many people talking past each other. I think part of that is just because there are few containers (I think that’s what they call them nowadays) that foster dialogue. I think we’ve got a terrific example to explore with the Fleischman et al. NEPA paper back and forth in the Journal of Forestry.

Anonymous posted this yesterday as a comment.

A said: “much boils down to talking past one another, (who said who said what about the relative formality of a hypothesis), ultimately disappointing in that regard.”

Anonymous found this new paper.. remember this journal article? and this response (r1) to the article (also Matthew published another response post here?) Well this is the response to the response (r2). The paper is attached here.NEPA article R2 and can be found online here.

FWIW, in this case, I don’t think it’s about the data, but about the claims in the first paper. If the original reviewers had pointed out that some of the claims were far beyond the data, then I think the second paper wouldn’t have been written. Here’s what Anonymous said:

“our paper tested no hypotheses” but it implied several that the other authors attempted to systematically test which they clearly stated, with the upshot being that the conclusions made needed formal hypothesis testing to match the strength of the claim

“our paper made no causal claims” but it clearly speculated about causes and the necessity for revising regulations, so is it not appropriate for someone to test those claims more formally?

Will be interesting to see a response to the response to the response. Really seems like the response to the response is to claim “not applicable!” whereas the intent of the original response was to question not the study as a whole but specifically the final conclusions drawn from it as resting more conclusions on the data than it can support

final note – it seems that the “response to the response” shifts the ground a little bit by claiming much more modest conclusions for the original study than that study itself made. the original article did indeed provide valuable trend data and kick off the conversation about what works and what doesn’t in an interesting direction, but it also claimed to reach conclusions about the role of CEs vs. EAs vs. EISs, conclusions about what to make of the relative abundance of litigation, and even further claims about the merits of policy change. the response to the response doesn’t really touch on these more ambitious claims. you can couch that as speculation all you like, but it doesn’t make the claim off limits for further evaluation.

general question on examples cited ; is it in any way historically demonstrable that NEPA-mandated public involvement led to the change of the 10am policy or allowable cut measures – inclined to think not, unless you collapse wildly divergent histories into something which NEPA can take credit for, somehow, and ignore NFMA)

Here’s the last paragraph of R2:

Ultimately, public comment periods, scientific analysis, and land management activities are tools the agency uses to achieve its goals of managing land in the public interest. Much like a fuels treatment, NEPA has costs as well as benefits, and a deeper understanding of what those costs are and how they can be minimized relative to their benefits would help the agency use the NEPA process more effectively. Although neither our analysis nor Morgan et al.’s directly addresses this big question, both of our analyses point to high levels of variability within the agency in terms of how NEPA is carried out. We suggest, as we did in our original article, that studying this variability may help the agency understand what works well, and what doesn’t, in the NEPA process.

Let’s compare this with what the original article said:

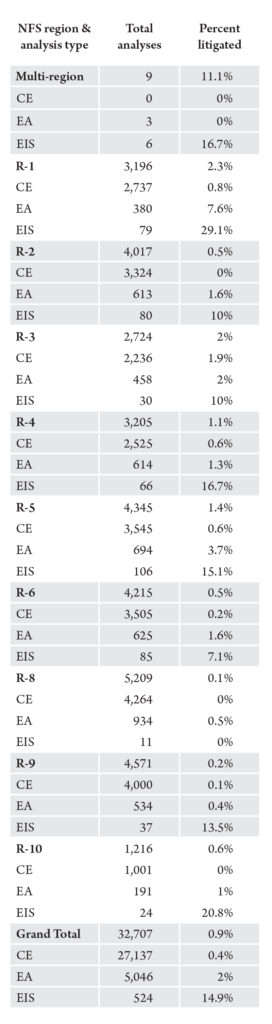

There has been much public debate on how the US Forest Service (USFS) can better fulfill its National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) obligations, including currently proposed rule-making by the agency and the Council on Environmental Quality; however, this debate has not been informed by systematic data on the agency’s NEPA processes. In contrast to recently publicized concerns about indeterminable delays caused by NEPA, our research finds that the vast majority of NEPA projects are processed quickly using existing legal authorities (i.e., Categorical Exclusions and Environmental Assessments) and that the USFS processes environmental impact statements faster than any other agency with a significant NEPA workload. However, wide variations between management units within the agency suggest that lessons could be learned through more careful study of how individual units manage their NEPA workload more or less successfully, as well as through exchanges among managers to communicate best practices. Of much greater concern is the dramatic decline in the number of NEPA analyses conducted by the agency, a decline that has continued through three presidential administrations and is not clearly related to any change in NEPA policy. This may suggest that USFS no longer has the resources to conduct routine land-management activities.

But then there’s alo the title to the original article: “US Forest Service Implementation of the National Environmental Policy Act: Fast, Variable, Rarely Litigated, and Declining.” Which seems like something of a stretch. But that’s fairly normal in today’s world.

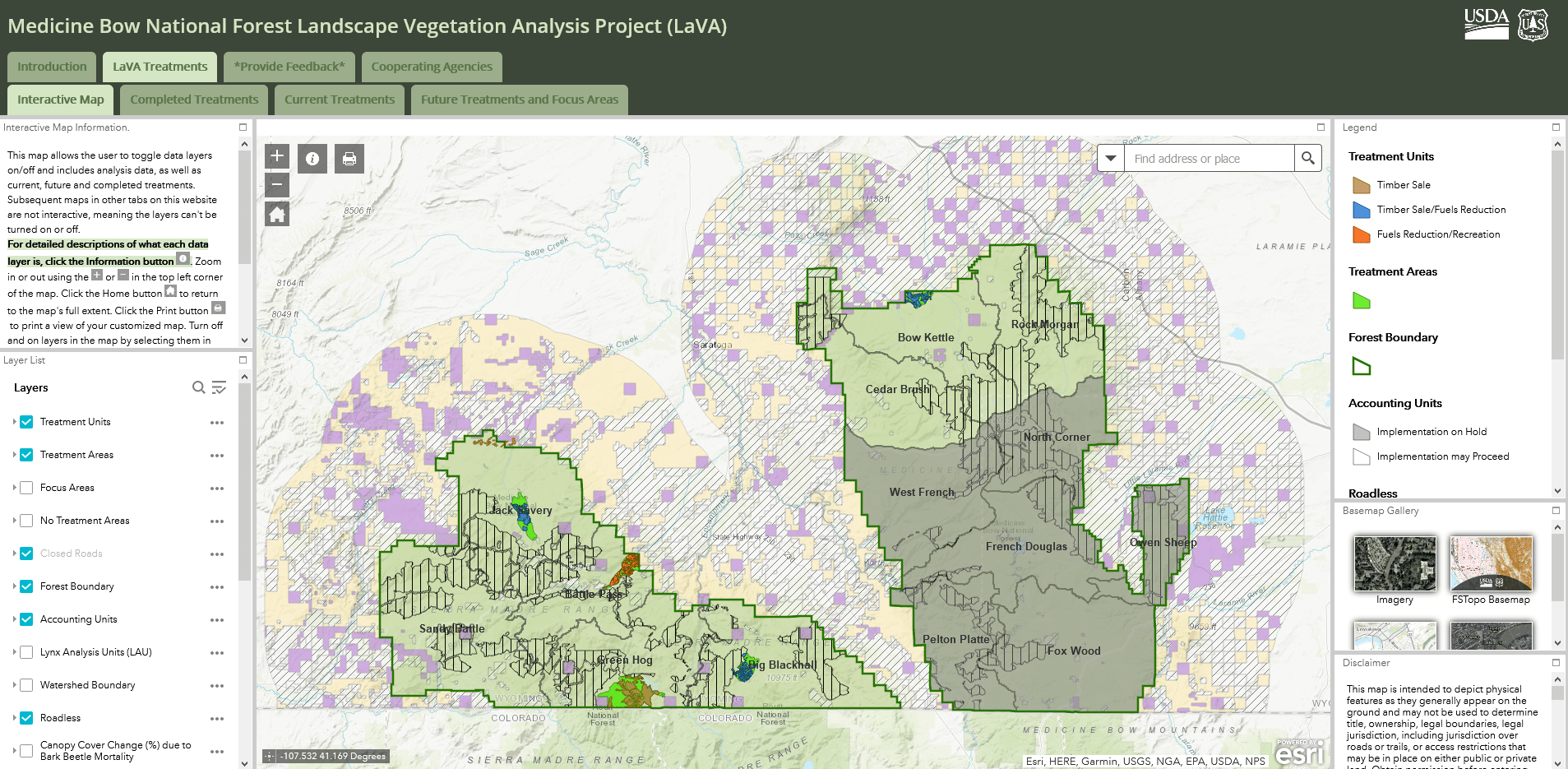

Here are my claims to knowledge- I was the WO NEPA Assistant Director for both Process Predicament, and for the initiation of the PALS database. Practitioners have always known that some project NEPA takes longer than others; and that some of the variation is due to intrinsic tendencies of the unit (or that specific ID team), some due to the nature of the project (and the perceived need for bullet-proofing), some due to what the unit considers appropriate ways of dealing with a variety of public concerns, some due to changes of personnel, and some due to the perceived urgency of the project and its relationship to other possibly more urgent projects. All these things are known variables, and have been described at the EADM workshops by stakeholders, if nowhere else. Then there’s internal strategizing about size and content of NEPA- Queen Mary vs. flotilla of small boats, and so on.

I don’t think the PALs database can tell us about those.. you need qualitative research (aka interviews) to explore those further. As Fred Norbury, the former EMC director used to say, “we treat NEPA as a cobbler shop run by each unit, when it would be more efficient as a NIKE factory.” However, as you may recall, efforts to centralize ran into obstacles in FS culture. My point being that I think we could get much further if we (1) pooled our academic and practitioner knowledge, (2) reviewed existing sources of information, and 3) jointly determined what questions are interesting and could be addressed best by which available analytic tools. Otherwise known as co-design and co-production of knowledge. I think we should try it for this example, with the ultimate goal of applying for a grant from NSF or NIFA, perhaps combining scientists from both studies as well as practitioners. Anyway, we’ll start tomorrow with “What are the questions we could jointly study?” “what benefits might accrue from obtaining the answers?”