Matthew’s post on oil and gas leasing reminded me of one of the annoying aspects of being involved in litigation, at least for me. I had been following climate and climate science seriously since the 90’s from the R&D perspective. And I found myself in NEPA, where conceivably we were supposed to use “the best science.”

NEPA asks the USG to look at the environmental impacts of its actions. It does not force the USG to choose the least impactful choice. And I have read many news stories about BLM O&G leasing that simply accept that “the judge said that they did not analyze the impacts correctly.” No one wants to hear the other side, or the details of the analysis. Especially when the impacts are about climate change, which is world-wide, obviously, and shall we say.. speculative, and contested.

This goes back to “what is speculative” and “how far should analyses go?”

You might wonder “how could this (the BLM didn’t analyze it right” happen so often?” “Can’t the BLM folks get it right?” But that raises the question, “is there a “right way”?

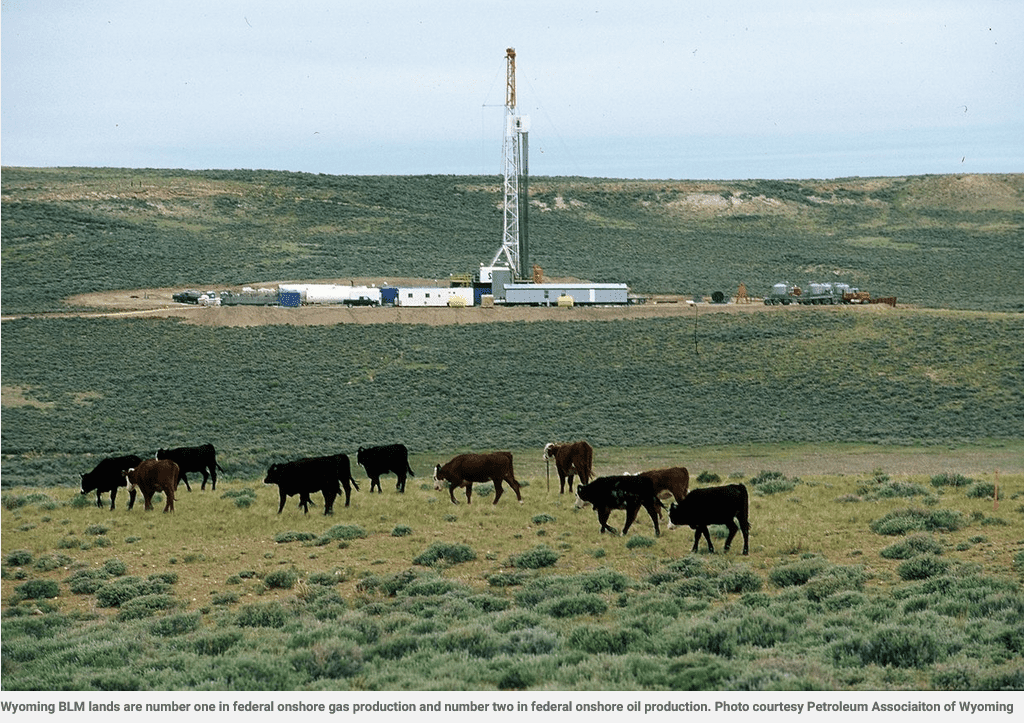

You don’t have to have a Ph.D. in energy sciences to think this through. Again, during the Obama Administration, CEQ had a number of listening sessions about analyzing climate change. At the one I attended, all the NEPA people said that analyzing climate impacts of use of fossil fuels is at the power plant permitting or other “use” stage, not the “getting it out of the ground” stage. Of course, there are impacts of “getting it out of the ground” and we have some idea of those, and they can be readily analyzed.

But let’s look at “how much will drilling one lease’s worth of O&G wells here in on the federal lands of the US contribute to climate change, and what will be the effects to the world, say, toad populations in Malaysia?”

Now if we look at demand, (or even our own history with forest trees) we note that substitution occurs when resources are not available from federal lands. As to oil and gas, we know where the other formations are on private land that could be tapped. And due to the vagaries of the investo-econosystem with some international security issues thrown in, we might get them instead from our friends (or not-so-friends) in Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and Iran. (That’s oil, but substitution also works for natural gas).

So do we figure out where substitution might occur from and analyze that? Not really. Of course, any of those countries could become unfriendly at the drop of a hat and your analysis would no longer be accurate (“approved with outdated NEPA”).

The assumption is that the impacts on climate change from this project will occur if the project is approved. And of all the coal and oil and gas being developed around the world, even if we believed this lack of substitution theory, how would we discern impacts from x amount of CO2? X being a tiny amount of the total. And we don’t know the impacts of even large amounts, in reality. Because we don’t know what will happen, and we don’t know how people and organisms will adapt. So we are making policy based on essentially some scientists’ best guesses. So how do you pick the scientists the judge will agree with in advance?

From my perspective, we are making USG employees jump through all kinds of bizarre analytical hoops. and most of us know that it’s all BS. Then there was the social cost of carbon, which is quite a silly number also. But it doesn’t matter which number you pick to analyze, the USG can still decide to go with actions that have some kind of negative impacts on climate change.

The fact is that some groups don’t want oil and gas on federal lands. Some groups don’t want oil and gas on private lands either, but if your favored tool is litigation, then going after private lands won’t work as well. As Chief Jack Ward Thomas said, DOJ settlements can actually be another tool the Admin has to gain their favored goals.

The frustrating part is not that some groups don’t want oil and gas drilling, and use critiques of analysis to get their way. That’s a legitimate policy tool that folks have been able to use to get their way. It was frustrating that most of us at the science end know that the numbers are bogus, and have to use them anyway. I actually think lawyers and judges know they are bogus also. Perhaps we’re all pretending to the citizens of the US that the Emperor is wearing fine clothes.