Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest, North Carolina

Old growth logging projects on national forests are almost sure to generate objections, but most likely they are in an area that was “allocated” to timber production in the forest plan. (Otherwise timber harvest would have to be for non-timber reasons, and there aren’t many of those to log old growth.) This thoughtful article examines the issue on the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest as it continues to develop its forest plan revision.

Williams and other conservationists argue that this stand of older trees and others like it are exceptional and should be conserved. The Forest Service currently says they are not sufficiently exceptional to be conserved.

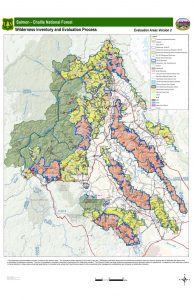

If a forest plan has been revised under the 2012 Planning Rule, we would know how much old growth is needed for ecological integrity, and old growth could be logged where there is “enough” old growth on a forest based on its natural range of variation (and where not prohibited by the forest plan). But there are only two plans completed under these requirements. Both have desired conditions based on what they determined to be the NRV (which is not an easy thing to do because of lack of reliable historical records). The Flathead also prohibits destruction of old growth characteristics and limits removal of old trees to certain circumstances. The Francis Marion includes this standard:

S37. Stands meeting the criteria for old growth as defined in the Region 8 old growth Guidance will be identified during project level analyses. Consider the contribution of existing old growth communities to the future network of small and medium-sized areas of old growth conditions including the full diversity of ecosystems across the landscape.

That is similar to the current Nantahala-Pisgah forest plan:

Steverson Moffat, the National Environmental Policy Act planning team leader of the Nantahala National Forest, told CPP that the current Pisgah-Nantahala national forest land and resource management plan requires that the forest designate large, medium and small patches of old growth to form a network that represents landscapes found in the Southern Appalachians that are well dispersed and interconnected.

A big problem with this approach is that this strategic and programmatic “designation” (of a “future network”) would probably occur outside of the forest planning process and maybe out of the public eye (unless the forest plan is amended each time it occurs). And unless a “network” has been fully described, there is no way to tell whether a particular proposed project area is necessary to comply with the forest plan. Which leads to that debate on a project-by-project basis, like we have here on the Nantahala-Pisgah.

On a 26-acre stand near Brushy Mountain slated for harvest, the Forest Service said the site meets the minimal operational definition for old growth defined in a Forest Service document known as the Region 8 Old Growth Guide. Even so, the stand won’t be protected since it “is already well-represented and protected in existing old-growth designations.”

How were those “designations” made? When that occurred, did the public know that it would mean these other areas would be subject to future logging, and did they have an opportunity to object then?

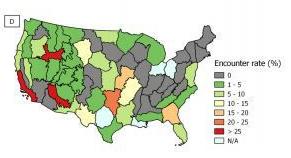

“Only one-half of 1 percent of the forest is old growth in the Southeast,” Buzz Williams of the Chattooga Conservancy told Carolina Public Press. “That is the reason within itself to leave it alone.”

“There is not a need to create (early successional habitat) right on top of old growth.”

The Forest Service disagreed. In an official response to the objections, the Forest Service wrote that while the Forest Service “should provide and restore old growth on the landscape,” this spot and others within the project are either not old growth or unique enough to protect.

I get that old growth should be allowed to “move” across a landscape over time, but that timeframe is even slower than the one for forest planning (note: humor). There would be little administrative risk in designating which areas would be preserved in a forest plan and which would not (subject to amendments in cases where designated areas are destroyed by natural events). Better yet, except on national forests that have an abundance of existing old growth (where would this be?), require an ecological reason to log old trees.

This is a debate that should be settled in forest plan revisions not passed on for objections to future projects. An attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center agrees:

“The question of protecting old-growth forests is very much a planning-based question — in terms of the big picture of the management of the National Forest and restoring its ecological integrity,” Burnette said.

“In light of broad-based community support for protecting old growth, it’s perplexing that the (Forest Service) would want to rush out ahead of the process during a time when the question of protecting old-growth forests in the future is being considered in the revision of the forest plan.”