Larry Harrell asked recently (with a *smirk* no doubt) if any species have gone extinct on national forests. Here’s a report (published in 2004) from the Center for Biological Diversity that documents 108 extinctions that occurred between the passage of the Endangered Species Act in 1973 and 1995. Two are noted on national forests. One was a mussel on the Carson National Forest. Here’s the other:

The San Gabriel Mountains Blue butterfly (Plebejus saepiolus aureolus) was known only from a single wet meadow within the yellow pine forest near the Big Pines Ranger Station, San Gabriel Mountains, Angeles National Forest, California [14]. Its host plant was Trifolium wormskioldii. At a minimum it was seen in 1970, 1980, and 1985. It has not been seen since 1985 [14]. It was not found in a 1995 survey which was a very wet year that would have encouraged reproduction if the taxon still existed [97]. The meadow was still wet, but had been made smaller due to the diversion of some of the water from the natural spring feeding it. The diversion of the spring by the U.S. Forest Service has been suggested as the cause of the species extinction [189].

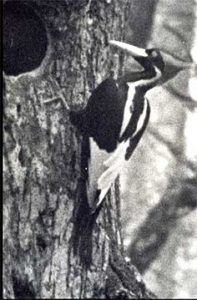

And it’s been another 20 years since then. Another species that seems obvious, but its extinction probably pre-dates this study is the ivory-billed woodpecker, which ranged throughout the southeastern forests, and was killed off by logging. The Ocala National Forest in Florida was established in 1908, but ivory bills had apparently disappeared from there by 1940. The last confirmed sighting was in 1944 in Louisiana. One of the unconfirmed sightings after that was on the DeSoto National Forest in Mississippi.

It would be good to see more like this:

One rare desert plant has been removed from the endangered species list, and another has been “down-listed,” thanks to successful recovery efforts in Death Valley National Park.

National forest planning has been a contributing factor to the delisting of grizzly bears in the Yellowstone ecosystem, and will be part of the consideration if Canada lynx are proposed for delisting.