As Matthew just posted, the Rio Grande National Forest has reached the penultimate phase of forest planning – the courtroom. Here’s a few other updates that address some things we have discussed here.

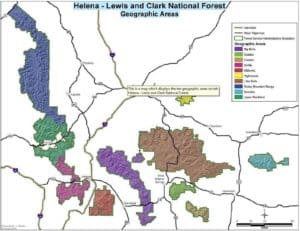

Helena-Lewis and Clark decision

The Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest has released its final revised forest plan after “a more than six year planning process.” This article provides highlights. In reference to travel planning, the forest supervisor indicated that since it had been completed in recent years, the Forest Service did not revisit those decisions in the forest plan (which doesn’t get the relationship quite right because travel plan designation decisions are not made in a forest plan, which I alluded to in a comment here).

Among the more controversial changes from the old forest plan are the replacement of elk hiding cover standards. According to the forest supervisor,

The standards became difficult and in some cases impossible to meet, Avey has said, due to changes on the ground such as high insect mortality in the forest. The 2021 plan uses “security areas,” defined as blocks of habitat away from roads and guidelines, rather than standards, for tree cover. The changes provide the agency more flexibility as land use or ecology changes, he said. Wildlife advocates have pushed back for years on the shift from hiding cover standards to security areas, saying the standards are both scientifically proven and enforceable.

The Forest wants “flexibility” and the Montana Wildlife Federation wants the plan to be “enforceable.” “MWF is looking forward to addressing this glaring oversight with the Forest.”

Here is the forest supervisor’s take on the 2012 Planning Rule:

Drafting the plan fell under a 2012 Forest Service planning rule, which Avey believes made for a much improved finished product that takes a more holistic approach at the landscape. The rule directs the agency to define “desired conditions,” with subsequent decisions needing to move towards those goals.

“It’s much more powerful and easier to understand, I think, for the public and our staff,” he said. “It will also keep these plans fresher into the future as opposed to how dated our ’86 plans were.”

The Outdoor Alliance has submitted comments on the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests Draft Revised Forest Plan that focus on recreation issues that we have discussed. One is high levels of dispersed recreation use, for which the Alliance has proposed designation of specific areas for high use “recreation emphasis.” Another is the effect (or not) of dispersed recreation on wildlife, stating that “the research on the effect of non-motorized, trail-based recreation on wildlife populations remains inconclusive,” so the Forests should “reconsider the limits on non-motorized, trail-based recreation within Wildlife Management Areas.”

Black Hills initiates revision

We’ve discussed (such as here) the new information about timber inventories on the Black Hills National Forest, and they have officially initiated the revision of the forest plan, which should produce a definitive answer based on the best available scientific information that will make everyone happy. To summarize:

Just after the last update was introduced in 2006, the Mountain Pine Beetle Epidemic ravaged forest vegetation for over 10 years. Jeff Tomac, Forest Supervisor of Black Hills National Forrest, discussed the impact this event had on the ecosystem. “Timber sustainability on the Black Hills National Forest will be one of the assessments that we will be working through and a lot of interest top many people in and around the Black Hills,” he said.

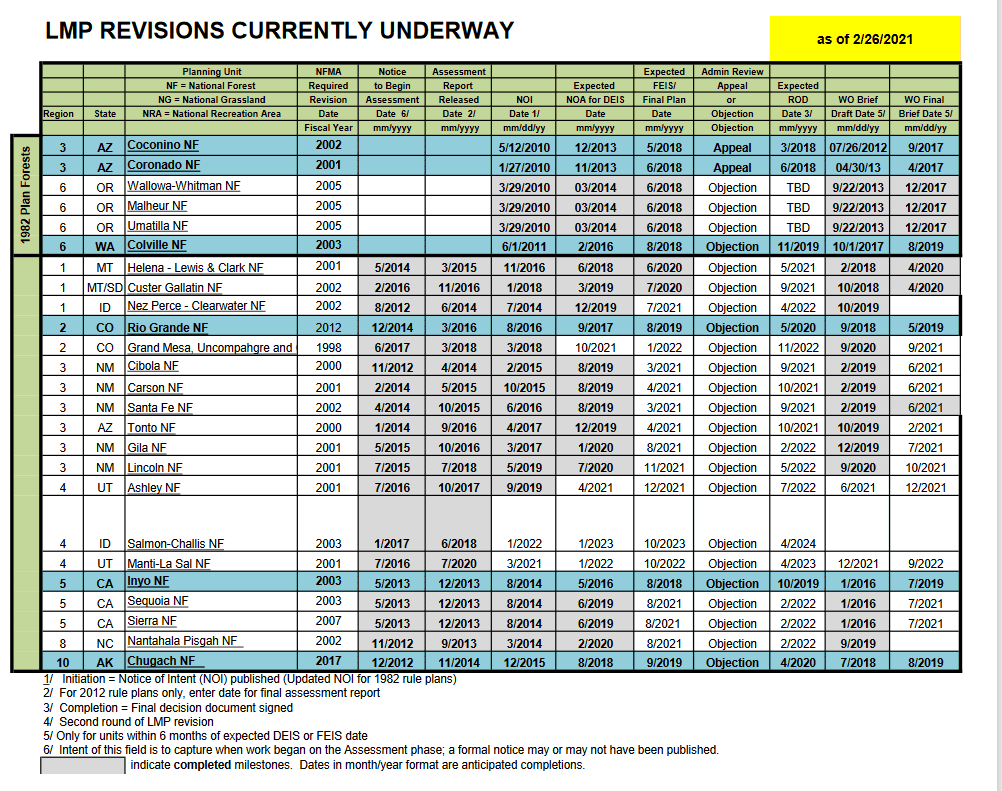

It is interesting that, while many forest plans have never been revised (and are over 30 years old), a few are on their second revision (the Wayne is another).