Earlier in September, a press release from the Greater Southeast Alaska Conservation Community (GSACC) was shared with this blog. It opened with:

On August 16, GSACC and four other organizations filed an administrative appeal of the Tongass Forest Supervisor’s decision to proceed with the Big Thorne timber project. The appeal went to to the next highest level in the agency, Regional Forester Beth Pendleton. The appeal is known as Cascadia Wildlands et al. (2013), and other co-appellants are Greenpeace, Center for Biological Diversity and Tongass Conservation Society.

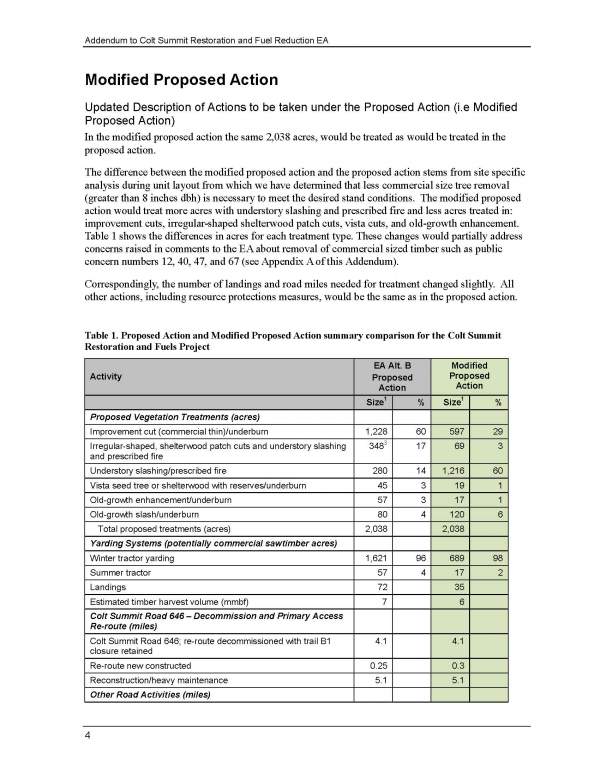

The project would log 148 million board feet of timber [enough to fill 29,600 log trucks], including over 6,000 acres of old-growth forest from heavily hammered Prince of Wales Island. 46 miles of new logging roads would be built and another 36 miles would be reconstructed.

Today, we get an update on the Big Thorne timber sale on the Tongass National Forest in Alaska in the form of this article, written by Dr. Natalie Dawson, one of GSACC’s board members.

“When you spend much time on islands with naturalists you will tend to hear two words in particular an awful lot: ‘endemic’ and ‘exotic’. Three if you count ‘disaster’. An ‘endemic’ species of plant or animal is one that is native to an island or region and is found nowhere else at all.”

-From Last Chance to See by Douglas Adams, author of A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

by Natalie Dawson

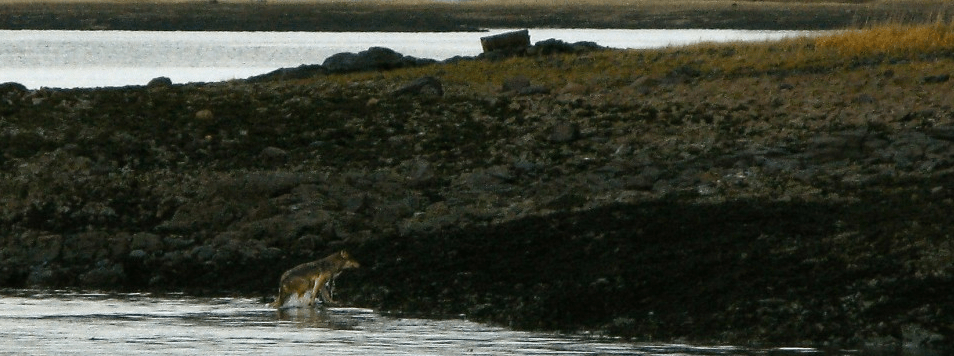

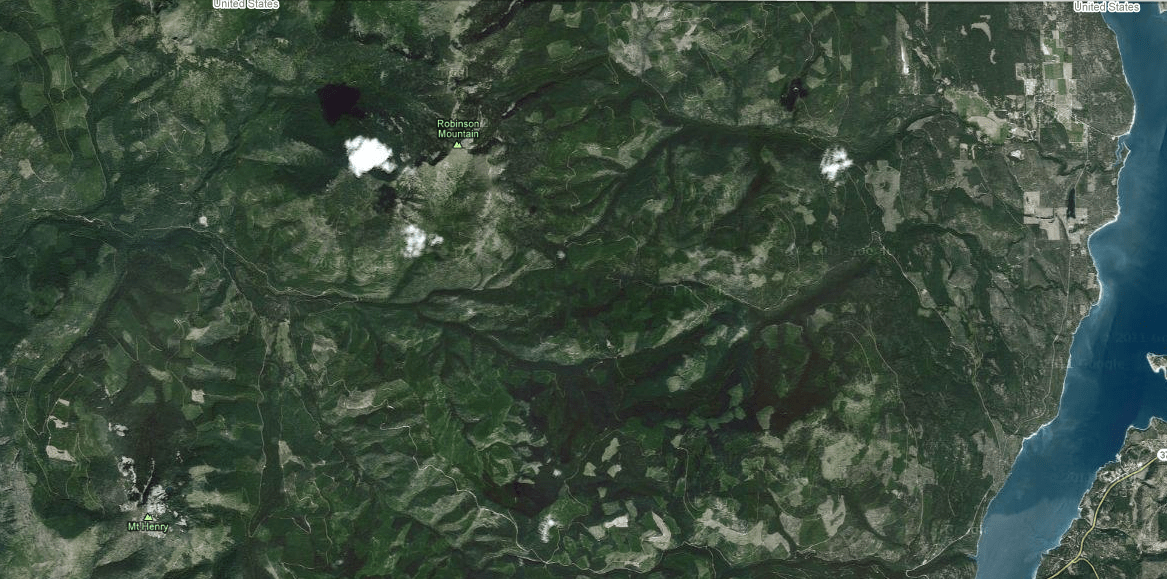

On the Tongass National Forest, we hear mostly about trees – whether it be discussions about board feet, acres of old growth, percentage of forest converted to “second-growth” or “the matrix”[*], our conversations tend to focus on the dominant plant species group that defines the rare “coastal temperate rainforest” biome. However, the Tongass is more than a forest, it is a conglomerate of islands, islands of different sizes, islands of different geologic and cultural histories, islands with or without black bears, grizzly bears, or wolves, the iconic species of Alaska. Because of these islands, there are unique, or, endemic, species of various size, shape and color across the islands. Though they have played a minimal role in management throughout the course of Tongass history, they are now rightfully finding their place in the spotlight thanks to a recent decision by regional forester Beth Pendleton.

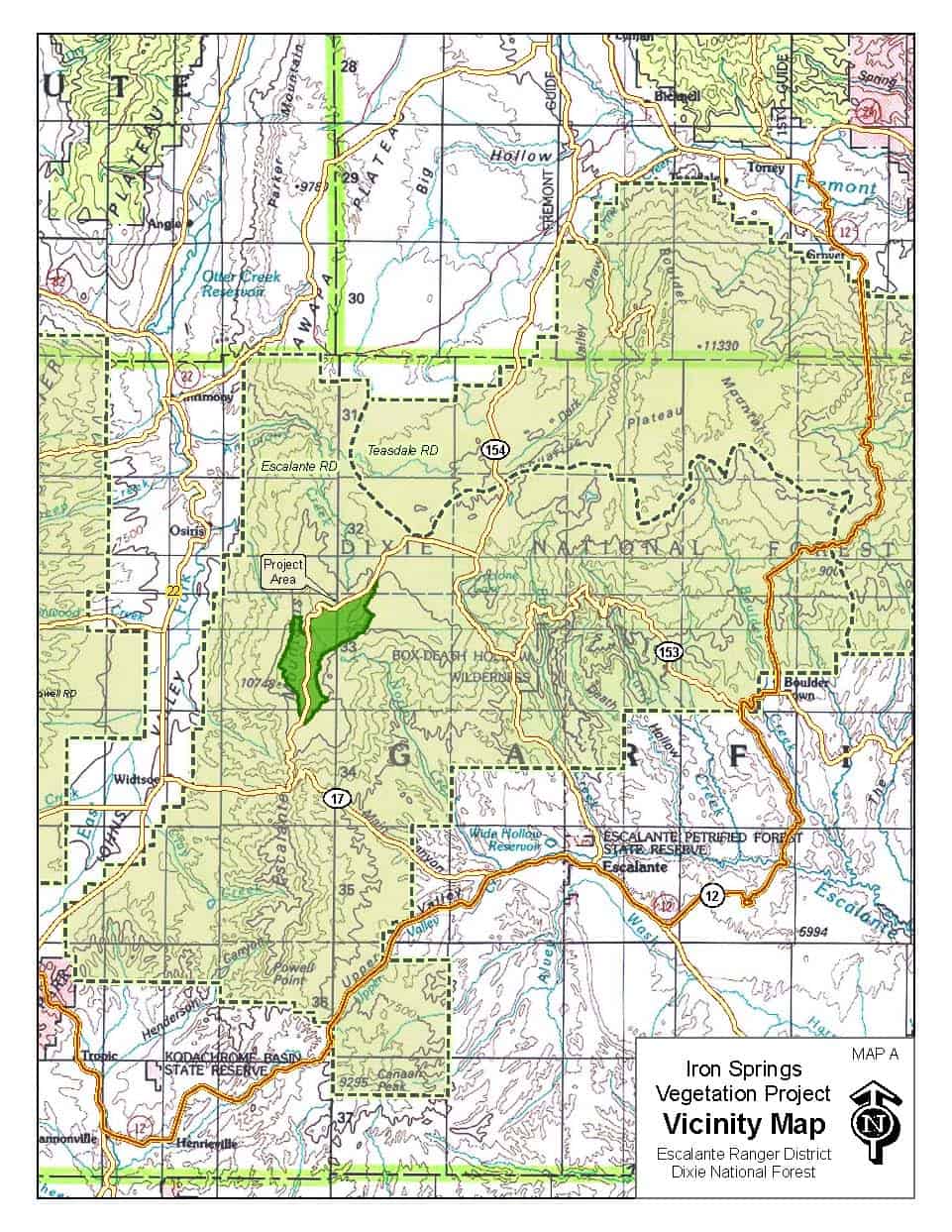

On Monday (Sept. 30), the US Forest Service announced its decision to reconsider the Big Thorne timber project. This project would have been the largest timber project on the Tongass National Forest in twenty years, taking 6,200 acres of old growth forest (trees up to 800 years old, 100 feet tall, and 12 feet in diameter) from Prince of Wales Island, an island that has suffered the most intense logging in the region over the past six decades. It is also an island that is home to endemic animals found nowhere else in the world.

Citizens of southeast Alaska and environmental organizations including GSACC jointly filed an administrative appeal on the Big Thorne timber project on August 16th of this year. Monday’s response comes directly from regional forester Beth Pendleton. In the appeal, Pendleton cited an expert declaration written by Dave Person, a former Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG) biologist with over 22 years of experience studying endemic Alexander Archipelago wolves on Prince of Wales Island, with most of his research occurring within the Big Thorne project area. Pendleton cited Person’s conclusion that “the Big Thorne timber sale, if implemented, represents the final straw that will break the back of a sustainable wolf-deer predator-prey ecological community on Prince of Wales Island…” Her letter states, “This is new information that I cannot ignore.” The response to the appeal requires significant review of the timber project before it can move forward, including cooperative engagement between the Tongass National Forest and the Interagency Wolf Task Force to evaluate whether Dr. Person’s statement represents “significant new circumstances or information relevant to” cumulative effects on wolves (including both direct mortality and habitat).

As one of my students today in class asked me pointedly, “So what does all this mean?” Well, it means that the largest potential timber sale in recent history on our nation’s largest national forest, on the third largest island under U.S. ownership, is temporarily halted under administrative processes due to an endemic species. It does not mean that this area is protected. It does not mean, that our work is done. Pending the outcome from conversations between the Forest Supervisor and the Interagency Wolf Task Force, especially under the current political climate within the state of Alaska, we may have plenty to keep us busy in the near future. It does mean that, even if only briefly, the endemic mammals of the Tongass National Forest received a most deserving moment in the spotlight. This could result in a sea-change in how the Tongass National Forest is managed.

This also means that science is being given a chance to play an important role in an administrative decision on our nation’s public lands, and two endemic species, the Alexander Archipelago wolf, and its primary prey species, the Sitka Black-Tailed deer, are forcing federal and state agency personnel to reconsider their actions. Science must continue to play an important role in the future of all activities on Prince of Wales Island. It is home to many endemic animals found only on a small percentage of islands on the Tongass National Forest, and nowhere else in the world. This lineup includes the Prince of Wales Island flying squirrel, the spruce grouse, the Haida ermine, and potentially the Pacific marten, which was only recently discovered on nearby Dall Island. The future of the Tongass timber program and human development on these complex islands are inextricably tied to ensuring a future for all other species in one of the world’s only remaining coastal temperate rainforests.

____

Dr. Natalie Dawson has done years of field work on endemic mammals throughout much of Southeast Alaska, studying their population sizes and distributions through field and laboratory investigations, and has published peer-reviewed scientific papers on these topics. She presently is director of the Wilderness Institute at the University of Montana and a professor in the College of Forestry and Conservation.

[*] What is the matrix? The conservation strategy in the Tongass Forest Plan establishes streamside buffers (no logging) and designates minimal old growth reserves, in an attempt to ensure that wildlife species on the Tongass remain viable. (Whether the strategy is sufficient for this is at best questionable.) The matrix is the expanse of habitat that is allocated to development (such as logging) or that is already developed, and which surrounds those patches of protected habitat.

UPDATE: Readers may notice that in the comments section a claim is made that the Sitka black-tailed deer are not endemic, but were were introduced. The Sitka black-tailed deer (Odocdileus hemionus sitkensis) were not introduced to Southeast Alaska; the Sitka black-tailed deer is indeed an indigenous, endemic species there.

Also, another commenter suggested referring to the article on the GSACC website, as at the bottom of the article one can find much more information about the Big Thorne timber sale and also the declaration of Dr. David Person regarding Big Thorne deer, wolf impacts. Thanks.