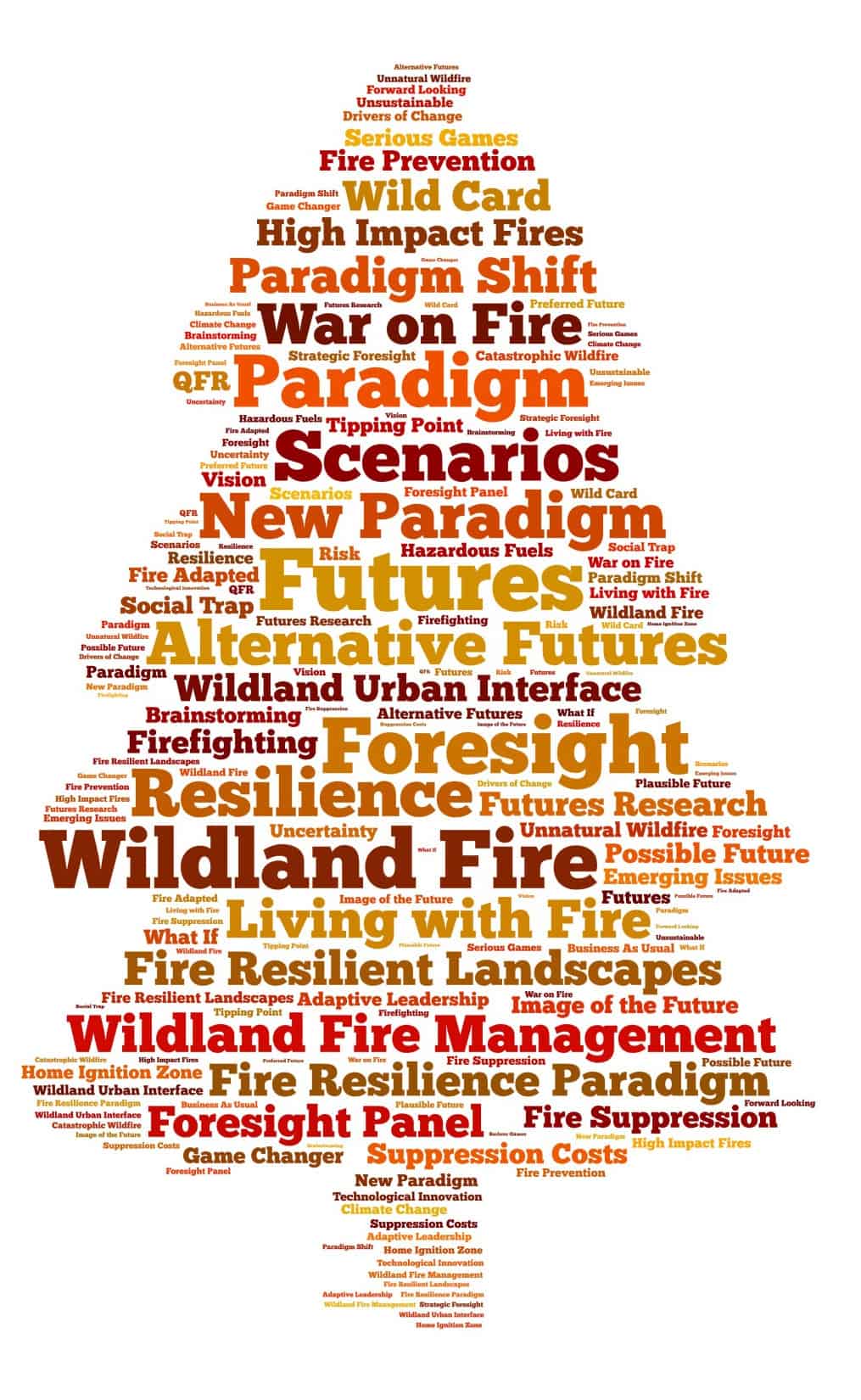

Our recent discussion about agenda-driven science reminded me that I’ve had a series prepared for some time on a related topic.

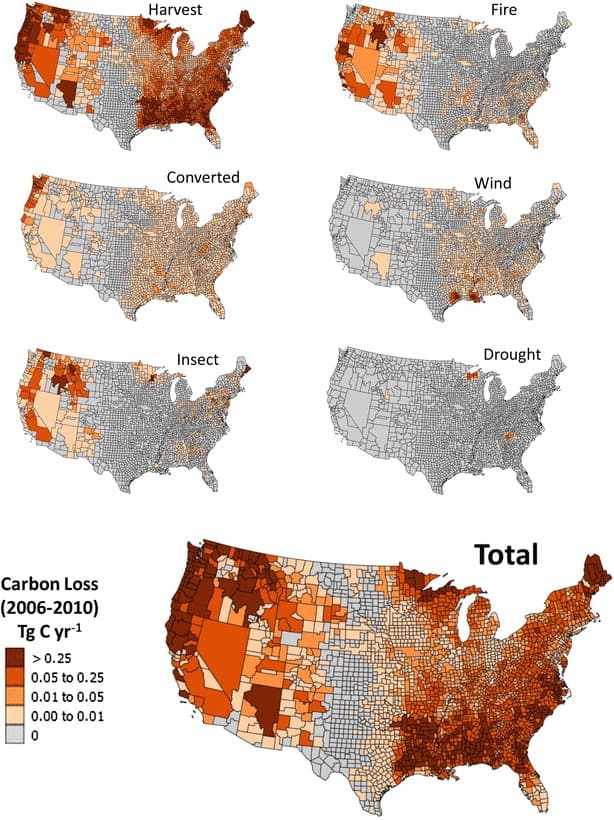

A while back we had a discussion about this paper and the implications. It started with some of our questions about https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5108824/figure/Fig3/“>this figure (seen above) from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5108824/“>this paper.

Note: I am not criticizing any individual involved. They were all extremely helpful to me, and if there is a problem it is due to the way the science biz is conducted. But I hope this little story gives non-scientists a glimpse behind the curtain of the production process. You may say “Sharon, you are so in the weeds” – but scientific research is based on details, so please be patient.

I followed the trail to the first author, and emailed her as to where she got the data for the map. Perhaps surprisingly, the trail went to a person we know, Todd Morgan at University of Montana! Small world. So I wrote him and he gave me an excellent answer.

A Presentation Problem

“One of the reasons why the harvest carbon data look so odd has to do with how they are displayed on these maps. Nevada is prime example of this, but it applies to several other areas in the west. The viewer sees huge geographic areas (e.g., the entire state of NV) shaded with a single “carbon loss” value, whereas most of the rest of the country is shaded on a county-by-county basis. Because of the way the TPO data (and possibly other FIA data) are stored in the database, and counties are often grouped together to prevent disclosure of individual landowner information, there are county groups or whole states with a single value. The paper briefly mentions this in the section “Timber product output data” (TPO 2007).

A possible way to deal with this “combined county” grouping is to take that single value and divide it among the number of counties it includes. So, in NV, the value of each county in NV would be 1/17 of the state total. Or one could contact the source of the data (like you did) and find out that the NV value for harvest is really from two small counties in western NV and the statewide value could be split between those two counties and the rest of the counties assigned a Zero value. That would help make maps that visually make more intuitive sense – i.e., the brown shaded area of NV would be very small geographically relative to the rest of the state – like can be seen in east Texas vs. west Texas.

Another solution to this would have been tabular reporting of state level values for harvest (and possibly other disturbances) would allow comparisons to other whole states. At the state level, one would see that the volumes for NV (should) make sense compared to other whole states (i.e., NV would be a very small value compared to most other states). A third way to make the maps make more visual sense would be to map Tg C per acre per year – in other words scaling the data by the acres of timberland – like was done in Figure 1 of the paper. Again, that would probably reveal amounts of carbon that “make more sense” so instead of comparing the total carbon for the State of NV to each individual county in the rest of the country, one could compare the carbon per acre in NV to the carbon per acre in other locations.”

*******************************************************************

By asking Morgan about this, I encountered the surprising (to me) fact that the people doing the study didn’t ask him before using his data. There are two problems with this.. one is that it’s considered bad form (or at least it was when I was a practicing scientist) to do that. The problem that concerns us here, though, is that the collector of the data (Morgan) and the authors of the study did not confer about the pros and cons of using this data, weaknesses, and strengths and ways of displaying it so it made sense, and so on. Finally, when the conclusions are drawn from the study, it seems like the collectors of the original data might have views worth hearing about what can be concluded using their data. So somehow this generally good science biz practice fell off the table. How often does that happen? I don’t know. Maybe I’ll apply for a research grant…:)