From the Spokesman-Review here via the Forestry Source. Note: “This is the first time that a tribe is doing environmental analysis for the forest service using state funds.”

Twenty years ago, the proposal being presented at public meetings in January for forest restoration and recreation projects on 90,700 acres in Pend Oreille County would only have been a pipe dream.

That was at the height of the “timber wars,” pitting pro-logging interests against environmentalists and bringing logging to a halt.

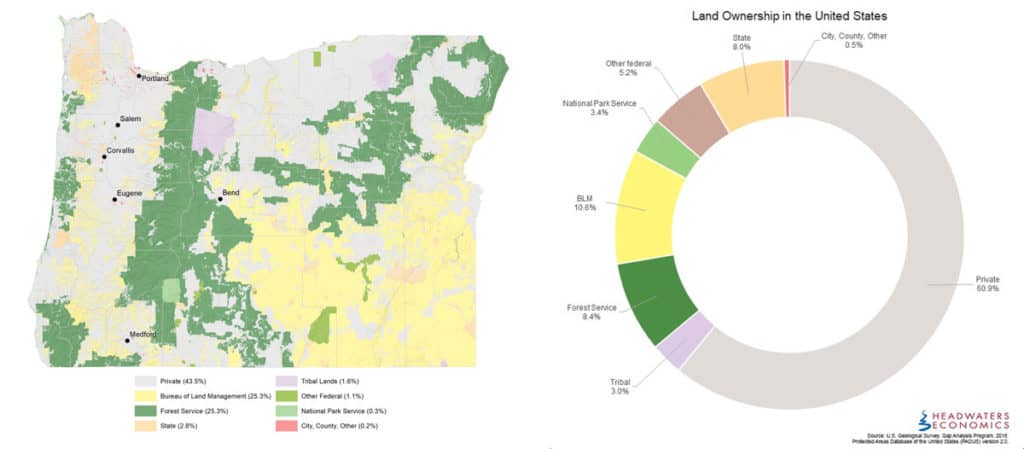

The project area north of Newport and east of the Pend Oreille River is a patchwork of tribal, state, federal and private lands. This is the first time that a tribe is doing environmental analysis for the forest service using state funds. When complete, it should vastly improve forest and watershed health for all land owners with a bonus of increased recreation opportunities.

Project area land owners are: Colville National Forest, 41,600 acres; Kalispel Tribe of Indians, 3,700 acres; Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR), 8,200 acres; private, 37,000 acres; and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 200 acres.

All the actual work in the project will be done on forest service land, but the partners hope others will follow, especially private timber land owners. The DNR and Kalispel Tribe have been working on forest health and watershed improvements on their land already.

This project is the culmination of years of increasing forest fire danger caused by poor forest management and a new spirit of collaboration between forest managers and some environmentalists. It is also a milestone for this new-age management, because it is the first project in the nation with so many partners working on this large of an area.

But it isn’t without challenges.

“Get past the feel-good part and reality is, it is hard to get agreements,” said Gloria Flora, project coordinator for the Sxwuytn-Kaniksu Connections Trail Project. “We proceed with caution.”

The Kalispel Tribe refers to the project as Sxwuytn (s-who-ee-tin), a Kalispel Salish word that roughly translates to connection or trail. This planning effort is also referred to as Kaniksu Connections to acknowledge the building and strengthening of connections and relationships across landscapes and boundaries.

Flora said that everyone won’t agree with what the group proposes and challenges in court are possible. But she said she feels that “old-school protests” need to change.

She points to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals statements last year in the ruling in favor of the Colville National Forest and its large A to Z forest restoration project in Stevens County. The court said the environmentalists objecting had a chance to be at the table in the planning process and should have been involved but weren’t.

Flora has been at the table for forest planning projects for many years. She has worked 23 years in forest management around the country with the past seven in this region.

She founded and directs Sustainable Obtainable Solutions, a nonprofit organization that works to ensure the sustainability of public lands. Her former forest service career included serving as forest supervisor on two national forests.

Given the scale of forest health problems in Eastern Washington, the DNR, federal agencies and other partners agree that to meaningfully reduce wildfire and forest health risks, it will take coordinated actions across land ownership boundaries at a watershed scale. The forest land owners can’t just work their patches independently or not at all.