Bears Ears co-management is said to be new and unique. Inquiring minds wonder… shouldn’t Tribal views always be taken into account? Are there legal differences in various places that matter? What is different and better about the Bears Ears approach? How does it compare to other Co-Management efforts?

Bears Ears co-management is said to be new and unique. Inquiring minds wonder… shouldn’t Tribal views always be taken into account? Are there legal differences in various places that matter? What is different and better about the Bears Ears approach? How does it compare to other Co-Management efforts?

As I read the cooperative agreement, I wondered..

It sounds to me like there’s much “coordinate” and “provide opportunities for input” in this document. It sounds perhaps like a Forest FACA committee. There’s even a “meaningful seat at the table before decisions are made.” As I read these, FLPMA also says something about coordinating with local governments. The meaning of that seems to be highly contested, will this work any better? And who has a “meaningless” seat at the table?

On the face, the Agreement it sounds like something both the BLM and the FS should always do with Tribes with historic ties to that piece of federal land. Isn’t it?

Would co-management actually mean decision-making authority rests in both entities, and have a conflict resolution mechanism if the two groups disagree? Does co-management give veto power over projects and activities the Tribes don’t want, or similarly, if the Tribes want a project or activity, and the Agencies don’t, what happens? Or do the legal authorities not really change and the Feds just have to take the views of the Tribes into account in some way.

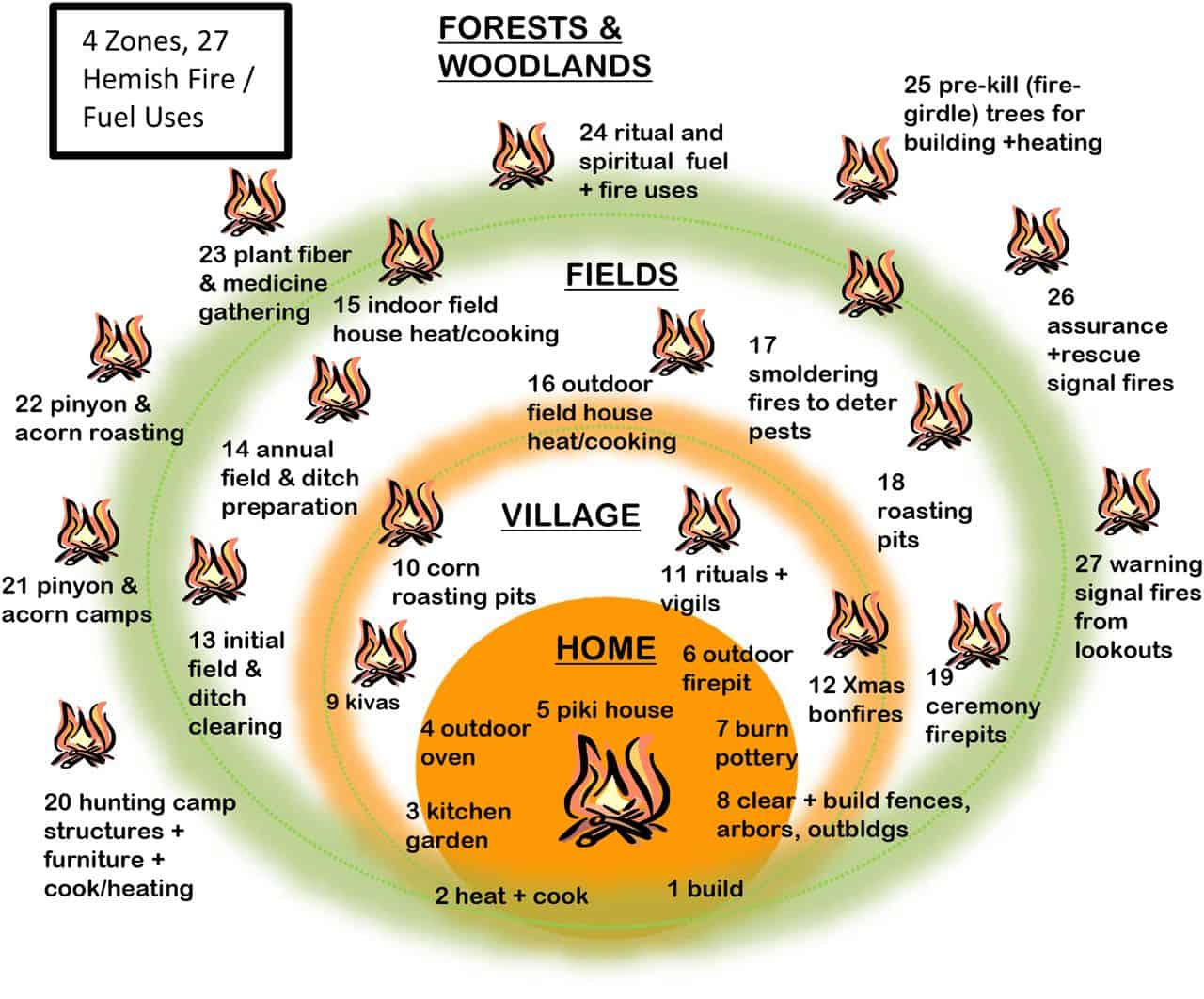

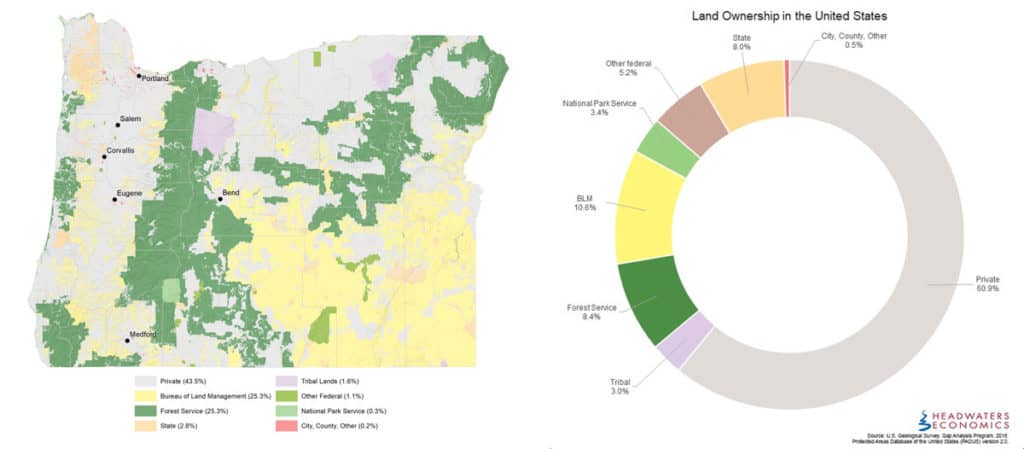

Tribes have unique and special knowledge based on their history and experience with the landscapes, places, plants and animals. Other local people whose families have lived in an area, in some places for centuries (e.g. descendants of Spanish colonists in the SW), also have local knowledge. To what extent should incorporation of that local information take place in a similar way?

Will Tribal co-management ultimately make it less likely that federal lands issues will be dealt with at the national level by national interest groups? That in some sense, non-Native locals were seen to be by some national groups as obstacles to correct management, but that doesn’t hold for Native locals? Anyway, check out the agreement for yourself and see what you think.

Here’s the text of the Bears Ears Co-Management Cooperative Agreement

C. In order to implement the direction in Proclamation 10285 and Proclamation 9558, the BLM and USFS agree to:

I. Ensure that Federal policies reflect the needs of Tribal Nations and that Tribal leaders have a meaningful seat at the table before decisions are made that impact their communities by centering Indigenous voices, including increasing the recognition of the value of traditional Indigenous knowledge and empowering Tribal Nations to make decisions for their cultural, natural, and spiritual values.

2. Honor applicable Executive Orders, Secretarial Orders, and Memorandums of Understanding including, but not limited to, Executive Order 13175 ofNovember 6, 2000, Consultation and Coordination With Indian Tribal Governments, Secretarial Order No. 3403: DOI and USDA Joint Secretarial Order on Fulfilling the Trust Responsibility to Indian Tribes in the Stewardship ofFederal Lands and Waters, and the November 16, 2021 Memorandum of Understanding Regarding Interagency Coordination and Collaboration for the Protection of Indigenous Sacred Sites.

3. Coordinate and consult with the Commission throughout land use planning and subsequent implementation-level decision-making processes concerning Bears Ears, including preparation of a monument management plan and a travel management plan.

4. Identify opportunities for development of initiatives to cooperatively conduct land management programs concerning Bears Ears.

5. Seek specific opportunities to involve the Commission in public land management activities concerning Bears Ears.

6. Coordinate, organize, and assure appropriate government professional and management involvement in programs within the scope of this Cooperative Agreement.

7. Ensure that Tribal knowledge and local expertise is reflected in agency decision making processes for Bears Ears. Develop and share information and data with the Commission, to the extent possible, to facilitate understanding of issues and sites, such as providing pictures and other information to Tribal Elders who cannot travel, and facilitate Tribal Nations’ work and engagement on the management of the monument.

8. Provide opportunities for input on implementation of interim guidance issued jointly or individually by the BLM and USFS, including the BLM’s interim monument management guidance issued on December 16, 2021, which directs the BLM to (a) inventory monument objects and values, (b) review existing discretionary uses and activities within the monument to detennine whether their impacts are consistent with the protection of the monument objects and values, and (c) update existing monitoring plans to ensure protection of monument objects and values.

9. Provide opportunities for input to the USFS review of existing discretionary uses and activities within the monument to deternine whether their impacts are consistent with the protection of the monument objects and values.

10. Provide opportunities to review and provide input on BLM and USFS policy guidance for the Bears Ears prior to issuance.