This post is based on an article written by John Marker and me that will appear in the October Society of American Foresters newsletter, The Forestry Source: http://www.nxtbook.com/nxtbooks/saf/forestrysource_201310/index.php#/11, and will also appear in the Fall issue of Oregon Fish & Wildlife Journal. The photograph was provided by Pacific Gas and Electric Co. and shows workers replacing a power pole burned in the Rim Fire, near Yosemite National Park in California.

Wildfires have become financial big-ticket items in the United States. The cost of fighting fires continues to escalate, the negative impact on people, wildlife and property grows, and damages to the land and its resources mount. But rarely do we hear discussion of these damages in terms the general public can understand, and when economic damage is discussed it is seldom a front page item. And when wildfire economics are discussed, it is usually in terms of suppression costs and property damage, little else. Other costs, such as for the effects of fires on water supplies, wildlife, and Public health, are not reported.

As this is being written in early September, we have received news that the Douglas Complex fires in SW Oregon have been 100-percent contained. This Complex was started by multiple lightning strikes on July 26 and was essentially comprised of two large fires, Dad’s Creek and Rabbit Mountain, each about 24,000-acres in size.

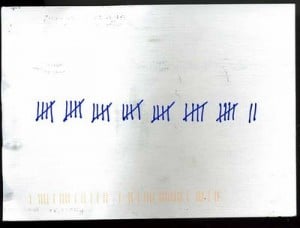

Three weeks after the fires had started, the August 16 Salem Statesman Journal reported: “The Douglas Complex already has burned 46,059 acres and was listed Friday as 65 percent contained. Suppression costs heading into Friday were calculated at $42.25 million, with 2,093 people assigned to it, according to ODF.” ODF is the Oregon Department of Forestry and is responsible for calculating costs of firefighting for the State’s services. But it is the only dollar figure given in the news account, and few readers have any idea what the number actually represents.

On September 4 the Medford Mail Tribune reported: “The 48,679-acre Douglas Complex fire burning just north of Glendale is now 95 percent contained. Total cost of fighting that fire is $51.76 million, ODF reported.” This is to illustrate how numbers commonly distributed by local and national media are often limited to basic fire suppression costs – in this instance, still more than $1,000/acre.

Our research has shown that the actual cost of damage caused by the Douglas Complex will likely be much closer to $500 million than to the current figure of $50 million. The fire might be contained, but many of its actual costs and damages are only now beginning to accrue.

The true scope of the problem

The $500 million estimate might sound outrageous to many readers, but examples are easy to come by in which it has been shown that suppression costs are likely to account for as little as 2% to 10% of the actual damages caused by a large wildfire. Some examples:

• In 2009 the Western Forestry Leadership Coalition released a report titled The True Cost of Wildfire in the Western U.S. The authors examined six major US wildfires, and compared suppression costs and tactics with “total costs.” Two examples were the 2000 Cerro Grande fire in New Mexico — suppression costs reflected only 3% of total damage estimates — and the 2003 Old, Grand Prix, and Padua fire complex in California, in which suppression costs were only 7% of total costs to 2005 – with total losses expected to increase dramatically in years to come (Dunn et al, 2005).

•

• The 2003 fires in San Diego and Southern California were catastrophic by any measure – 24 fatalities, more than 3,700 homes destroyed, and suppression efforts were $43 million. However, in 2009 Matt Rahn of San Diego State University presented findings that put suppression costs at less than 2% of the total long-term cost of the fire (www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Y8Ef9qc0F0).

•

• The 2002 Hayman Fire burned 138,000 acres and cost $42 million to suppress. In 2004 Dennis Lynch of Colorado State University estimated that an additional $187.5 million in losses had accrued within a year. Suppression costs were only 18% of the total, and Dr. Lynch stated, “I recognized the need to follow costs into subsequent years to more completely identify a fire’s true impact.”

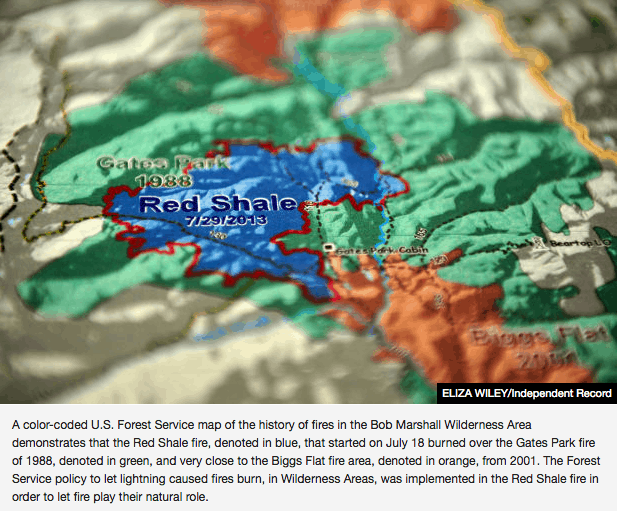

On July 12, 2010 National Association of State Foresters released a briefing paper titled State Forestry Agency Perspectives Regarding 2009 Federal Wildfire Policy Implementation. The paper avers that State Foresters have no say so in how the Federal Interagency and Interdepartmental Wildland Fire Management Community fight fires that threaten communities and natural resources, and that they would prefer that the Feds implement aggressive fire suppression strategies for any fire with a chance of burning private land and property.

Most State Foresters, the report notes, recognize that safe and aggressive initial attacks are the time proven best suppression response to reduce fire damage and keep suppression costs down – but recognize that the federal agencies are not likely to do so. They also recognize that Federal wildfire management policies impact state fire suppression efforts when Federal fires move across jurisdictional boundaries and burn state protected lands and private property. As such, the federal agencies have increased risk to families, communities, and wildlife by allowing some wildfires to burn without containment efforts, and are not providing credible explanations for doing so — not to State Foresters’ satisfaction at any rate.

These “let it burn” wildfires are allegedly for resource “benefits” and fire fighter safety, but often blow up, crossing onto state-protected land, putting communities at risk, and placing tremendous burdens on the states to control fires escaping from Federal lands.

This is a serious issue in states and counties where the federal government manages 50, 60 or even 90 percent of the land, and pays no land taxes. Further complicating the situation is an apparently influential group of people claiming wildfire is “natural” and the land will “heal” and everything will be better if nature is allowed to “take her course” — they do not explain, however, why such “ecosystem services” can’t be provided more effectively, safer, and with far less risk, fear and cost to taxpayers and wildlife via prescribed fires, ignited by people with stated objectives and written plans.

By mid August of this year the federal government had spent more than $1 billion fighting wildfires in the West, creating an estimated $10 billion to $25 billion in actual costs and damages. During the same time states and local fire units have spent hundreds of millions more for fire fighting. On August 21, 51 wildfires of significant size were uncontrolled. On August 22 the US Forest Service announced it was going to take more than $600 million from non-fire programs to pay its anticipated 2013 fire fighting costs.

What can be done?

There is little discussion of local economic damages caused by these fires other than structural losses, and often such losses are reported without mentioning the dollar amounts involved. However, the federal agencies are constantly challenged by members of Congress to reduce fire fighting costs, but without any sense of total fire costs.

Four years ago we were faced with the same problems and same questions, and it appears little has changed: these problems took quite a while to become established, and they will take sometime longer before they can be resolved. At that time a small group of individuals with similar backgrounds, interests and concerns in these matters asked ourselves what we could do to help resolve these problems. It was easy enough to come up with examples and complaints, but it was difficult to figure out how to make things better – particularly for such a small group.

The result of these discussions was an informal ad hoc – and truly grassroots – effort we titled the “Wildfire Cost-Plus-Loss Project.” Our intent was to develop analytical tools and sources of information that could be used by most citizens and not limited to agencies, professional organizations, or special interest groups.

The focus of much of our efforts was to design a simple tool that could be used effectively by almost anyone to assess the true damages of large wildfires. Target audiences were students, journalists, landowners, residents, elected officials, insurance adjustors and resource managers. Our initial efforts resulted in: 1) development of a “one pager” wildfire damage checklist/accounting form that could be used by almost anyone with access to the news; 2) a peer-reviewed article published online with an appropriate federal agency, including instructions for using the one-pager; and 3) a public informational website for anyone to use who was interested in the topic or use of these tools.

One-pager worksheet: www.wildfire-economics.org/Checklist/One_Pager_Checklist_2009.pdf

Peer-reviewed online publication with a federal agency: www.wildfirelessons.net/Additional.aspx?Page=240

Informational website (“under construction”): www.wildfire-economics.org/index.html

These efforts were generally well received and promoted on local, statewide, and national media and during several high-level meetings, but have never been properly field tested or adopted. In our opinion, not considering the true economic impact of wildfires to governments, businesses, and people is an unfortunate omission. For resource managers it is difficult to explain the realities of fire protection and its nuances to Congress and to citizens directly affected by these events. The lack of communications also implies that the land has no economic value for production of resources or public enjoyment. To the public the impression can be that it is government waste spending money fighting fire if there are no damages.

The “one-pager”

The focus of much of our group’s efforts was to design a simple tool that could be used effectively by almost anyone. Target audiences were students, journalists, landowners, residents, elected officials, insurance adjustors and resource managers.

The one-page checklist is intended to make initial estimates – based entirely on available data and personal estimates — of total fire costs, and to ultimately be used in conjunction with a comprehensive ledger for better tracking costs and losses over time. We believe the use of these tools would better inform land and resource managers in the management of water, fuels and wildfires by identifying true costs of decisions and allowing better judgment in the establishment of resource use priorities. Such uses would also generalize discussion topics and terminology for better communication with the public.

The checklist is divided into 11 categories: Suppression costs; Property; Public health; Vegetation; Wildlife; Water; Air and atmospheric effects; Soil-related effects; Recreation and aesthetics; Energy; and Heritage (cultural and historical resources). Each of the categories was considered in terms of direct costs (e.g., fire suppression, lost lives, evacuations, burned homes, etc.), concurrent indirect costs (fire preparedness equipment and training, fire insurance premiums, air and water quality, aesthetics, etc.), and post-fire costs (long term damages to society and the environment; e.g. loss of timber, crops, and wildlife habitat, chronic human health problems, reservoir sedimentation, etc.).

By using this basic approach we think the economic effects of large wildfires can be readily quantified, compared and described in terms understandable to our lawmakers and to the general public. By combining this data with digital spreadsheets, we think better ecological, economic and strategic decisions can be made in the management of our common lands and resources.

Conclusions

Few people seem to understand the critical importance of our nation’s natural resources to the future of the United States. Calculating economic damages may not be the best way to describe the total impact of wildfire on the land and people, but it is a method of creating awareness of damage by using a vehicle that most people understand: money. An analysis of actual wildfire damages provides needed context for evaluating protection and prevention programs, as well as overall natural resource management goals and objectives.

While we have focused on economics we are very much aware of biological considerations, their complexities, their importance to meeting the natural resource needs of 300 million people — but that is for another study. Now might be a better time to test our earlier efforts and conclusions, and perhaps the Douglas Complex provides an ideal circumstance for doing so.