Here is an editorial about spotted owl economics that has been going the rounds of a number of email networks since it was published four days ago, on May 3rd:

http://www.conservativeblog.org/amyridenour/2013/5/3/the-shameful-and-painful-spotted-owl-saga-shooting-stripes-t.html

This was posted on Amy Ridenour’s National Center Blog, and was written by Teresa Platt, who is listed as the Director of the Environment and Enterprise Institute at the National Center for Public Policy Research. I’m guessing “right wing think tank,” by the title of the organization and Ridenour’s history, and note that Platt often blogs about topics regarding our nation’s natural resources:

http://www.conservativeblog.org/amyridenour/author/blogplatt

I’d never read this blog before, but apparently some of my wildlife biology, range sciences, and rancher friends do — those are the circles in which this has been making the rounds, including a personal email from Platt requesting a wider distribution.

In general, I am in agreement with Platt’s thoughts – however, I think these animals are more rightly referred to as “hoot owls” (the most common type of owl in North America), rather than “wood owls.” I’m going to stick with Wikipedia on that one, until someone explains to me why they think spotted owls have been here “since the last ice age,” whereas historical evidence indicates they may have arrived just a few decades in advance of the more common striped hoot owl.

The Shameful and Painful Spotted Owl Saga: Shooting Stripes To Save Spots

By Teresa Platt

Posted May 3, 2013 at 1:20 PM

Our federal government prefers spots and is moving forward with a million-dollar-a-year plan to remove 9,000 striped owls from 2.3% of 14 million Western acres of protected spotted owl habitat. Our government is shooting wood owls with stripes to protect those with spots; to stop the stripes from breeding with the spots.

It had to come to this.

The 1990 listing of the Northern spotted owl under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) gave the bird totem status in management decisions.

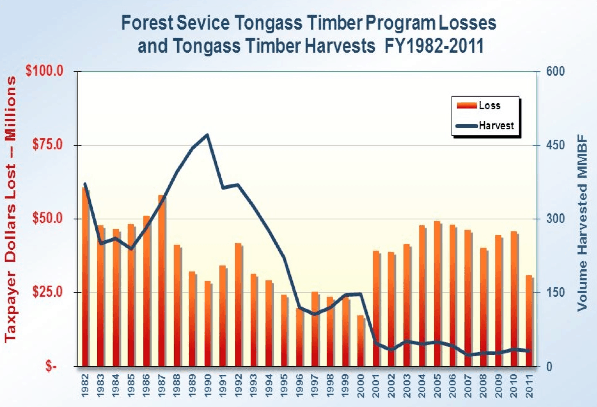

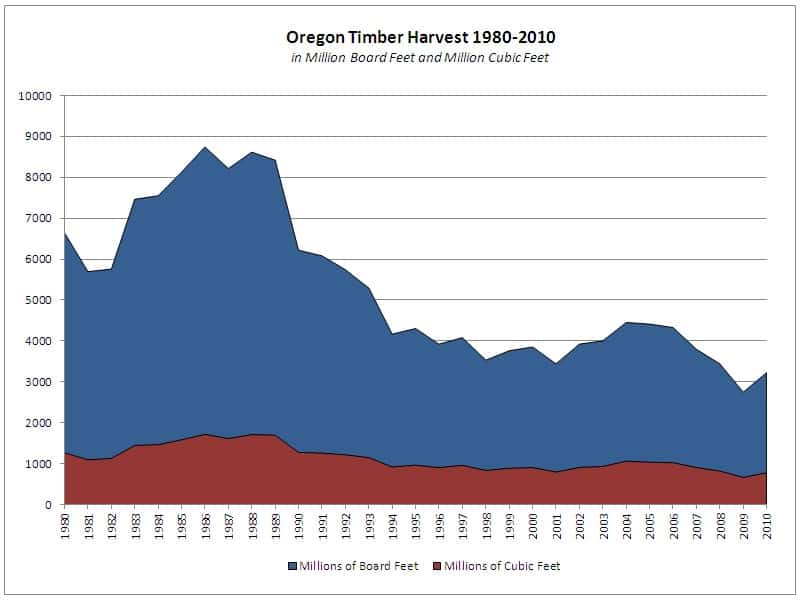

It didn’t work. Spotted owls declined 40% over 25 years. Timber sales on federal government-managed lands dropped too. Oregon harvests fell from 4.9 billion board feet (1988) to less than 5%, 240 million board feet (2009). Beyond the jobs and business profits from making lumber, the Federal and County governments used to benefit from these harvests too. Harvests down: tax receipts down. Today, with cutbacks in Federal budgets and sequestration, the States are arguing about how much of your tax dollars the Federal government should give them to keep impoverished County governments afloat in timber-rich areas.

Beyond competition from barred owls, and after years of not enough logging, mega-fires fueled by too many trees now threaten spotted owl survival. An exhausted veteran of the spotted owl wars, who lives dangerously close to a federally-“managed” forest that is expected to go up in smoke soon, explained:

“You have to realize that even moving a biomass project forward takes a court battle. No salvage of dead or burned timber — it just rots. Not much thinning or fuel reduction – without a two-year court fight the Forest Service usually loses. Hell, the agency is still fighting lawsuits over the Sierra Nevada Forest Plan Amendment started in ‘97 — after four revisions and several court decisions — the Greens just keep suing until they get what they want.”

Taxpayers pay for the conservation plans, recovery plans, and action plans, many stalled in court.

Taxpayers pay for all the lawsuits too, on both sides.

Taxpayers pay the salaries and pensions of government workers fighting fire and those shooting striped owls in order to give, temporarily, an advantage to ones with spots.

All this sacrifice and the spots just keep declining and the stripes just keep on coming.

The Northern spotted owl might very well be the most expensive avian sub-species on the planet.

Invasive or just mobile?

It is theorized that striped and spotted owls were once the same species of wood owl before separating into East and West Coast versions during the last Ice Age. The common striped barred wood owl (Strix varia) has expanded its range westward, establishing itself at the expense of the less aggressive, less adaptable and smaller spotted wood owl (Strix occidentalis).

By 1909, barred owls were found in Montana. They made their way to the coast, taking up residence in British Columbia (1943), Washington (1965) and Oregon (1972).

The owls, striped or spotted, are so closely related they successfully interbreed and their fertile offspring, “sparred owls,” are hybrids that look just like spotted owls. The ESA does not protect the hybrids or their offspring so the birds are breeding their way out of the ESA!

Says Susan Haig, a wildlife ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, is exasperated by the interbreeding:

“It’s a nasty situation. This could cause the extinction of the Northern spotted owl.”

The ESA measures and categorizes, then stands steadfast against change. It is attempting, by shotgun, to separate the birds.

Are these kissing cousins from the East invasive and unwanted when they turn up out West? Or just mobile and happy to mix it up with their spotted relatives?

Whatever, and wherever, they are, striped and spotted owls are not the only birds moving around.

111 species, almost 20% of the total bird species in North America have expanded into at least one new state or province with 14 species expanding into more states and provinces than the barred owl. Changing climates and habitats are the cause of 98% of range expansions. The birds go where the food is. 38 states or provinces have gained at least 10 new bird species, some moving into a niche inhabited by an ESA-listed avian cousin.

Beyond birds, the last Ice Age killed off the North American earthworm. It’s since been reintroduced, only to be labeled — by our government scientists — as an invasive species, an undesirable. And — oh no! — earthworms are beating millipedes in the game of survival.

The policy we embrace today for striped and spotted birds can be transferred to other birds and other animals, even earthworms. If this continues, will we be reduced to digging up and killing earthworms to save millipedes?

The ESA is written thus and lawsuits by “green” groups — many paid for by our tax dollars — are herding us in this direction.

Stripes, spots, species, subspecies and stocks

In the Kingdom of Animalia, the Phylum of Chordata, the Class of Aves, the Order of Srigiformes, are two Families of birds of prey: the typical owls (Strigidae) and the barn owls (Tytonidae).

The Strigidae Family is the larger of the two Families with close to 190 species, covering nearly all terrestrial habitats worldwide, except Antarctica. 95% are forest-dwelling; 80% are found in the tropics.

The Strigdae Family includes 11 species of the genus Strix, characterized by a conspicuous facial disk and a lack of ear tufts. They are known as screech owls, wood owls, the great gray, the chaco in South America. The Ural wood owl alone boasts 15 sub-species in Europe and Northern Asia.

Within this Strix genus, in North America, the barred wood owl is broken into three sub-species (the Northern varia, georgica in Florida and helveola in Texas), with a fourth (Strix sartorii) found in Mexico.

The spotted owl species (Strix occidentalis) is broken down into three sub-species ranging across the western parts of North America and Mexico. The “threatened” Strix occidentalis lucida of Arizona and Mexico, the California spotted owl subspecies, Strix occidentalis occidentalis, and the endangered Northern spotted owl, Strix occidentalis caurina, the sub-species of greatest concern. The Northern spotted owl ranges from California, through Oregon and Washington, and up into Canada.

You can break this down even further, if you’d like, into regional sub-stocks of sub-species. If you have the time (our government does) and the money (our taxes), you can follow family units, individuals, and all the new hybrids, the result of striped owls breeding with spotted ones.

The Wise Old Owl Asks, “Who Pays?”

This summer there will be more megafires in our overstocked Western forests, often followed by mudslides from the denuded hillsides next spring.

Another “green” group will file suit to stop another timber sale or attempt to stop government workers from shooting stripes to save spots.

Since the spotted owl wars resulted in the export of so many timber jobs, Northwest timber communities contribute far fewer tax dollars to the communal treasury, so the costs of megafires, mudslides and lawsuits will be borne by Eastern and urban taxpayers. That’s where the people—and the taxes—are.

The striped owl may be relentlessly working its way West, but its costs are steadily moving East.

——————————————————————————

Teresa Platt is the Director of the Environment and Enterprise Institute at the National Center for Public Policy Research.