File this one under “the more you know.” It can also be cross filed under “we told you so.” Also, there’s plenty of scientific evidence and research out there that would refute much of what Idaho State Forester David Groeschl says below.

From the Associated Press:

BOISE, Idaho (AP) — The amount of carbon dioxide being released into the atmosphere from forest fires in the U.S. West is being greatly overestimated, possibly leading to poor land management decisions, researchers at the University of Idaho said.

Researchers in the study published last week in the journal Global Change Biology say many estimates are 59% to 83% higher than what is found based on field observations.

Healthy forests are carbon sinks, with trees absorbing carbon and reducing the amount in the atmosphere contributing to global warming. Forest fires can release that carbon.

“Part of the reason we’re talking about this is that there’s a narrative that has circumvented science,” said Jeff Stenzel, the lead author and a doctoral student at the university. “What that can lead to is management decisions that can exacerbate rather than mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.”

The study used field data from a 2002 wildfire in southern Oregon and a 2013 wildfire in central California that, the authors of the paper said, included one of the largest pre- and post-fire data sets available.

Typically, the study found, about 5% of the biomass burned in a forest fire as opposed to other estimates of 30% and public perceptions of 100%.

Former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke in late 2018 cited carbon released from forest fires as a result of poor forest practices on federal land and a need to increase various management practices.

Forest fires usually leave behind standing dead trees, the study said, that could be mistakenly counted as releasing carbon in other estimates. The carbon remains in those trees and is slowly released over decades. Even then, the study found, much of that carbon is recaptured in new growth following the forest fire.

Overall, the study found, forest fires in the U.S. West in the last 15 years have emitted about 250 million tons of carbon, about half of many estimates.

Idaho State Forester David Groeschl said carbon emissions are a consideration when it comes to making decisions about forests on the 2.4 million acres (987,000 hectares) the state manages, but so are other factors.

In deciding where to log, Groeschl said, the state considers weather and climate, insect and disease, fire frequency and severity, milling technology, and local, regional and global economics.

When a forest is logged, the resulting wood products retain that carbon, he noted. When a fire moves through state-owned forests, he said, salvage logging removes standing dead trees and trees likely to die and so captures that carbon in wood products rather than allowing it to be slowly released over several decades.

He also said that forest restoration efforts following logging or a fire speed up the return of a forest that otherwise could take decades.

“We get carbon sequestration going as quickly as possible,” he said.

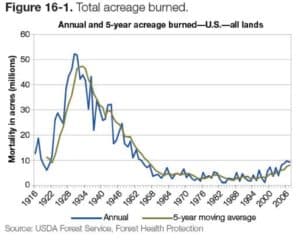

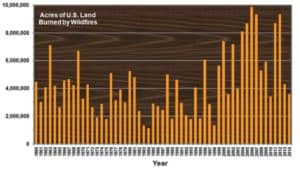

Wildfires have become more frequent and more severe in the last 20 to 30 years, Groeschl said, which is also a factor when it comes to logging state lands.

“The longer we grow it, the greater the risk of loss and carbon emission happening,” he said.