Scientific information is conditional on the approach to the study (framing), discipline(s)involved, methodology used, and the specifics of time and place. The more information expands, the more we know, even though it might feel like we are the blind person dealing with the elephant. Yet there is a balance between accepting the conclusions and understanding that for most topics, what you know is a a function of the step you’re on and not the final story. And as the climate (and people and whatever) changes, there may never be a “final story.” Just note the ubiquity of the expression in scientific papers “previous studies concluded x, but we have found y.”

Here’s one example of Stillman et al.’s work from Bird Pop!. There a link to the paper on the blog site.

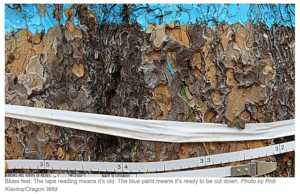

But the simple assumption that more fire always equals good news for a post-fire specialist wasn’t holding up. Stillman’s earlier work, in collaboration with IBP, his PhD advisor UCLA Professor Morgan Tingley, and the US Forest Service, showed that Black-backed Woodpeckers prefer to nest near the edge of severely burned patches. Now fledgling woodpeckers, hatched in nests within burned forests, were moving out of the burn and into adjacent forest that burned at low severity or sometimes hadn’t burned at all.

A new story began to emerge. Perhaps Black-backed Woodpeckers nest close to the edges of burned patches so that, upon fledging, their young can take cover in unburned or less severely burned patches nearby — presumably to take advantage of greater vegetation cover and avoid predation. “We started thinking of the food-rich high severity burn as a grocery store and the high-cover low severity burn as a nursery,” says Stillman. “If you’re going to build a home, you want to place it close to both the food source and the nursery!” But if this was indeed what was going on, you’d expect survival of juvenile woodpeckers to be higher in the less severely burned areas with more live vegetation.

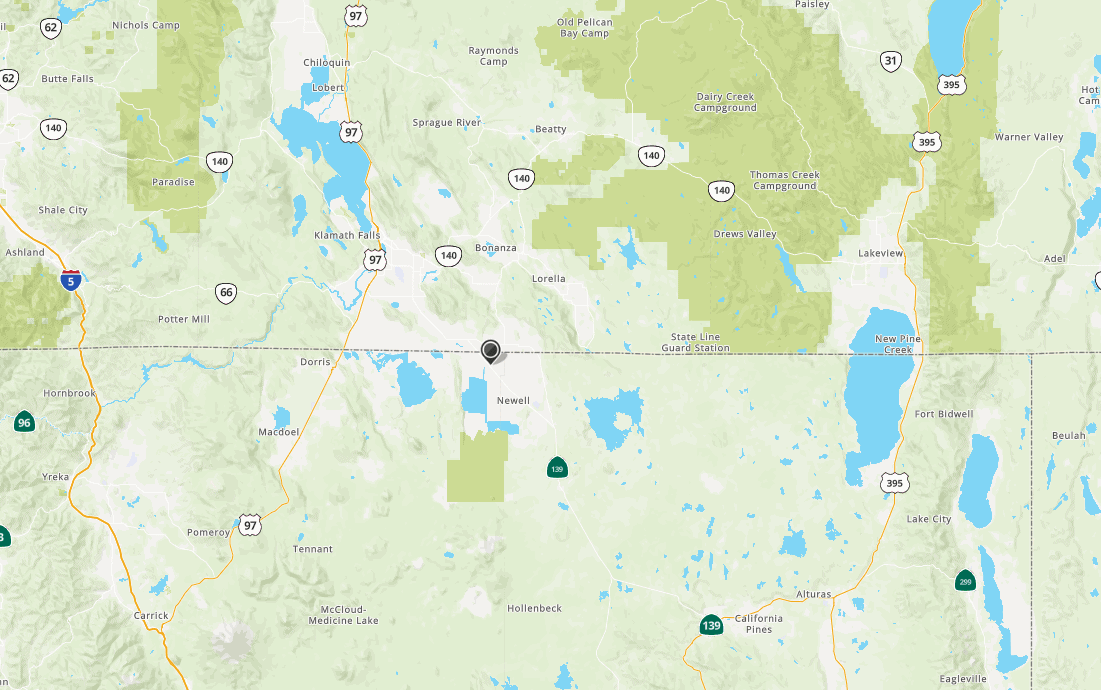

To test this prediction, Stillman and collaborators tracked the habitat use and survival of 84 fledgling Black-backed Woodpeckers from 39 nests in seven different recently burned areas in the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Mountains of Washington and California. Tracking during the first 35 days was done the hard way — hiking many rugged miles with handheld receivers. As the juveniles got older and dispersed, tracking was done by driving and with the generous help of the skilled volunteer pilots of LightHawk Conservation Flying. “We expected survival to be lower in the high-severity patches compared to low-severity patches — and that’s what we show in this paper. However, it was surprising to us just how much of a difference it made,” says Stillman. “If you’re a fledgling Black-backed Woodpecker, you have a 53% chance of surviving 35 days if you spend your time in low-severity burned patches — about average for a baby bird. But if you instead choose to spend all your time in the high-severity burn (which is good habitat for adults), your chance of surviving 35 days plummets to just 13%.” Most fledgling deaths were due to predation.

Another surprise: the identity of the predators. Most juvenile Black-backed Woodpecker deaths could be attributed to birds of prey including Cooper’s Hawks, Northern Goshawks, Red-tailed Hawks, and even a Western Screech-owl. Apparently if you are a bird of prey, fledgling woodpeckers in open stands of burned snags are the easy-to-grab, juicy hamburgers.

Previous research has shown that increased pyrodiversity yields more diverse habitat types across the landscape, which in turn increases diversity in the bird community. But this study and Stillman’s other dissertation research shows that pyrodiversity can be a good thing even for a single species. This is an example of habitat complementation: when a species has different habitat requirements for different parts of its life history. Forest managers can support and enhance pyrodiversity through management practices before fire, and by protecting pyrodiverse areas after fire.