Kudos to the Mount Hood National Forest for its excellent story map about last summer’s Riverside Fire. It’s an interesting overview and a great use of Esri’s GIS technology.

More Agreement on Wildfire: The Hewlett Foundation

I became acquainted with them because they fund the State of the Rockies polls, the questions of which seem to lead toward conclusions that the group supports (IMHO), and are then used in a variety of outlets and op-eds to support those views in a seemingly coordinated strategy. So I was looking around for what else they do, and ran across this wildfire strategy.

Prescribed fire policy and management. Prescribed fire, also referred to as prescribed or controlled burning, involves intentionally lighting a fire in an area after careful planning and under controlled conditions to achieve specific natural resource management objectives, such as wildfire risk reduction, improved water quality, or improved wildlife habitat. Prescribed fire is currently underutilized as a management tool that can be safely used across private, state, and federal lands, including near developed areas, under the right conditions.

Tribal leadership. Tribes throughout the United States have used fire as a resource and cultural management tool since time immemorial. After European settlement, Indigenous communities were largely prohibited from continuing their fire management practice, yet many remain uniquely positioned to provide leadership on wildfire policymaking and practice.

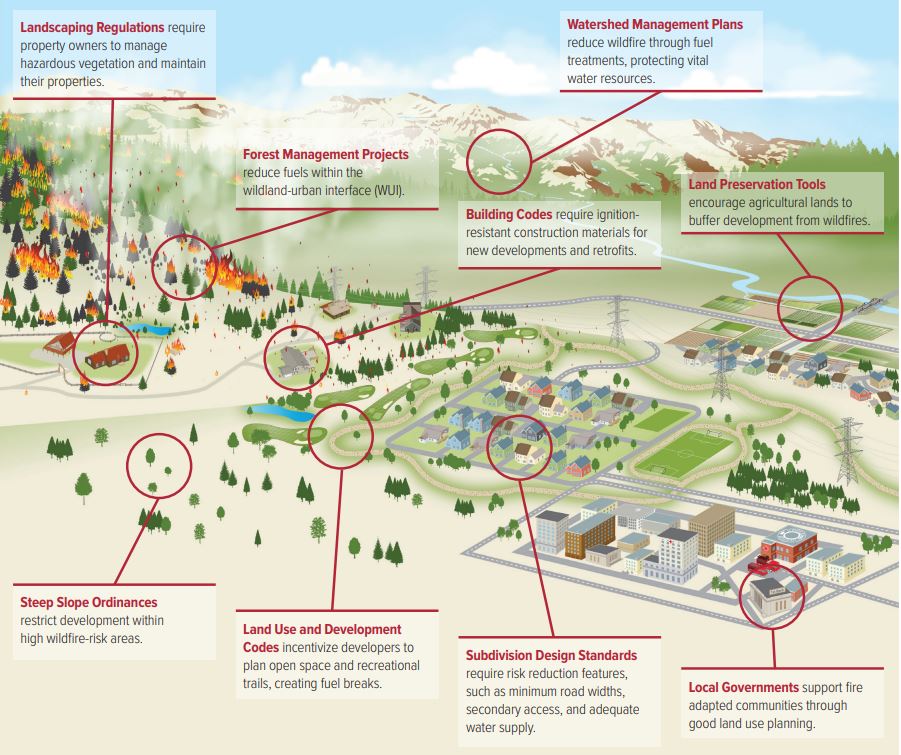

Land use planning in the wildland-urban interface. Many communities in the Western United States were and continue to be developed with little to no regard for meaningfully reducing wildfire risk. Recognizing that fire is an inevitable and often necessary part of the landscape through the West, communities must become fire adapted. The alternative is continuing to lose life and property to extreme wildfire events. Land use planning includes a variety of tools local governments can use to better prepare its existing and future communities for wildfire risk.

While prescribed fire is the star, mechanical treatment is also involved. They also have grants for improving agency decision-making, and use of woody material.

Hewlett’s strategy will focus on encouraging use of prescribed fire because it is one of the more effective and cost-efficient means of managing vegetation for multiple purposes, including hazardous fuel reduction and ecosystem restoration or maintenance. Unlike managed fire, prescribed fire can be used near developed areas and across private, state, and federal lands, and it can be done at times that mitigate communities’ exposure to smoke. Prescribed fire also reduces surface fuel to enable easier fire management, which mechanical thinning may not do. In some cases, prescribed fire should be used in conjunction with managed fire and/or mechanical thinning.

….

Grantees can help ensure that land management agencies are using the best available decision-making tools and policy options to improve strategic planning, access existing capacity, and track resource use.

……

For example, the foundation will support grantees exploring innovative funding mechanisms through development of industries that utilize the types of woody materials that come from forest thinning.

Sounds like some folks we know may be eligible for these grants..

Biden Nominates Homer Wilkes to Oversee Forest Service

President Biden has recycled former Obama nominee Homer Wilkes as his Undersecretary of Agriculture for Natural Resources and the Environment. Dr. Wilkes’s bio is impressive:

Dr. Homer Wilkes, a native of Port Gibson, Mississippi, currently serves as Director of Gulf of Mexico Ecosystem Restoration Team. He is oneof the five Federal Executive Council member to oversee the rebuilding of the Ecosystem of the Gulf of Mexico after the BP Oil Spill of 2010. He served as the Acting Associate Chief of USDA/Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) in Washington during the period of 2010-2012. Dr. Wilkes’ tenure with the United States Department of Agriculture span’s over 41 years. During his tenure he has served as State Conservationist for Mississippi; Chief Financial Officer for NRCS in Washington, DC; Deputy State Conservationist for Mississippi; and Chief of Administrative Staff for the South Technical Center for NRCS in Fort Worth, Texas.

Dr. Wilkes also served as Naval Supply Officer in the United States Navy Reserves from November 1984 – Aprl-2007.

He received his Bachelors, Master of Business Administration, and Ph.D. in Urban Higher Education from Jackson State University. He also successfully completed the USDA Senior Executive Service Candidate Development Program (SES CDP) through American University’s Key Executive Leadership Certificate in Public Policy. Dr. Wilkes and his wife Kim, currently reside in Ridgeland, MS. They have three sons, Justin, Austin, and Harrison. He enjoys fishing, restoring antique vehicles and family activities.

Insofar as he has no experience with the Forest Service, which under the current organizational chart is the only agency Wilkes will oversee, does his nomination suggest that Vilsack will reunite NRCS and the Forest Service under NRE?

How Will the Forest Service Deal With the Challenge of Current Crowds and More Commercial Permits?

There’s a bipartisan bill in Congress to make it easier for folks to get permits for commercial recreation on National Forests. I don’t know if more (outfitters and people) are better but it should be interesting to discuss!

Jonathan Thompson of High Country News, seems to think more tourism can be better.. than the alternative in this piece.

In its place, despite the relatively primitive conveniences of this national monument, is the hint of commercialism that comes wherever tourism trumps every other way of making a living. And there are so many people now, intent on adoring the place so thoroughly that they wear it down like water on sandstone. They stream through relentlessly in cars and buses, their cameras clicking…..

Maybe the national monument designation has drawn more people. But what’s the alternative? Would leaving it as it is — open to oil and gas leasing, uranium mining, or wind or solar energy development — really keep the crowds at bay? And even if it did, at what cost?

According to this school of thought, commercializing federal lands is fine, as long as it’s for tourism. Now, if climate change is the Most Important Thing, I’d think we’d want to have uranium mining and wind and solar energy development more than people using gas-powered vehicles and planes to get to places for fun; but.. maybe not. There are also the impacts of more people on water supplies and waste disposal, and the fact that tourism has low-paying, not family wage jobs compared to other industries. We’ve all seen this happen throughout the west. I think the social and economic justice facets of these questions have not been adequately explored. Thompson also has a story on crowds on the public lands.

Meanwhile, the Denver Post had an this story: Colorado Guides Can’t Get Enough Permits on Federal Lands.

Some quotes:

“It is arguably absurd to place so many barriers in front of the opportunity for the public to go with the assistance of a professional,” Wade said, because guided tours are less likely to harm the environment. “To limit that is absolutely puzzling.”

If you have 200 people with 10 units of impact each versus 20 people with 20 units.. (we can all do the math, it depends on whether more people would ultimately come with guides and how much less likely they are to harm the environment).

In some places, agencies won’t issue permits because they haven’t conducted environmental assessments and don’t have the staff to conduct those assessments. The result is effectively a freeze on hiking tours in places such as Blanca Peak and Little Bear Peak, according to Wade, as well as on backcountry skiing at Berthoud Pass in Clear Creek County.

The Forest Service did not respond to a Denver Post email this week asking whether the agency is unable to issue recreational permits because it lacks the staff to do so.

What else would they be doing? And is this the best use of the recreation staff’s time when they’re already overburdened keeping up? Many other folks who have this problem simply contract or do their own with FS oversight. It sounds like, though, some don’t believe they have impacts, individually or cumulatively. And of course, some outfitters guide recreationists on activities fairly low on the Pyramid of Pristinity, including OHVs, snowmobiles, mountain bikes and so on. I don’t know about rafting and heli-skiing. It is true that guided tours might get people to behave better but I don’t think that’s known empirically. And what kind of monitoring occurs by the FS of these folks?

These permitting problems exist nationwide. Guide groups from all of the Mountain West states have asked Congress to address the issue since 2019, as have companies in Alaska, California and West Virginia. Senators representing nearly every western state are cosponsoring the current bill to do so.

When permits are issued, they’re too narrow in scope, guides say. For example, the Mountaineers, a Seattle-based nonprofit guide group, teaches rock climbing in a national forest in Washington. But its permit does not allow it to teach the very similar skill of rock scrambling, the group’s conservation and advocacy director Betsy Robblee told a House subcommittee on public lands hearing on June 8.

“We spend an enormous amount of staff and volunteer time navigating the various permitting processes of land management agencies. These convoluted systems are equally as challenging for under-resourced land managers to administer,” Robblee said.

So we have the crush of more people. Is it better to get more guided opportunities or will that just add more people to the mix. Is it better to get more people out there? If more trails and floating opportunities are by reservation, how will the FS decide what is the right ratio for guided versus independent users? I’m sure they already do that in places).

Finding Agreement: Some California Environmental Groups’ Agreement on Forest Management

Thanks to Susan Britting of Sierra Forest Legacy for sharing this Novermber 2020 Forest Management Statement signed by a broad coalition that included the following groups:

California Native Plant Society ▪ California Wilderness Coalition ▪ Central Sierra Environmental Resource Center ▪ Defenders of Wildlife ▪ The Fire Restoration Group ▪ The Nature Conservancy, CA Chapter ▪ Sierra Business ▪ Council Sierra Forest Legacy ▪ The Watershed Center

Statement on Forest Management

California forest conditions

• Well managed forests provide many critical benefits for nature and people including clean air, clean water, wildlife habitat, carbon storage, recreation and more.

• Current conditions in many fire-prone forests of the Sierra Nevada and elsewhere in California are degraded and not healthy due to past logging practices, fire suppression, drought, and climate change. From the perspective of forest health and resilience, there are too few large trees, too many small trees, and an excess of “surface and ladder fuels” that significantly increase the risk of high-severity wildfire.

• California is experiencing high-severity wildfire in larger landscapes and at larger scales than is desirable from an ecological perspective.

• Threats to forest communities from high-severity wildfire are increasing and need to be addressed.

• There is an urgent need to restore more natural forest structure and reintroduce beneficial fire so that forests continue to provide important ecosystem services and pose less of a threat to

life and property.An integrated solution: communities and landscapes

• We support an integrated strategy to reduce the risk of high-severity wildfire near communities and across the forest landscape, including public and private lands.

• The strategy needs to utilize all tools in the toolbox: ecologically based forest thinning, prescribed fire, managed fire, cultural burning, working forest conservation easements, defensible space, home hardening, and emergency response.

• Different actions and priorities are appropriate across the landscape: 1) near communities, the primary goal should be protecting lives and property through steps like defensible space, structure hardening, emergency response, improved ingress/egress, and reducing unplanned human ignitions; 2) in the mixed forest landscape, we should work to increase forest resilience and mature forest structure using actions like ecological forest thinning and prescribed and managed fire while reducing unplanned human ignitions and hardening infrastructure; 3) in roadless and wilderness areas, the primary management tools should be cultural burning as well as prescribed and managed fire.

• There is a need for an all-lands approach, including public-private and tribal partnerships, to achieve these goals.

• We support the commercial use of woody material removed from forests (e.g., saw logs, mass timber manufacturing, woody biomass for heat and electrical generation, and added value wood products development) where the goal is increasing forest health and resilience and as long as species and ecosystems needs are met.

The letter even has a very nice glossary.

I find nothing to disagree with here (I could get picky about specific words but..). I’ve found that for some E-NGOs, woody biomass is a non-starter (it seems to invoke Europe and southeastern US pellet exports), and and some seem to be against commercial use of woody material from National Forests. I think it’s important to note that these groups (who have to live with the “burn in piles or do something else” challenge staring them in the face) support useswith constraints (“when the goal is”.. and “as long as”). Certainly the devil is in the details, but some groups seem to assume that those details can’t be handled appropriately through existing mechanisms or those to be developed in the future.

Does anyone have a similar statement from groups in other western states?

NFS Litigation Weekly June 18, 2021

Things were a little busier this time. Forest Service summaries are here: Litigation Weekly June 18 2021 Email

Court documents related to each case are provided by the links below.

COURT DECISIONS

Western Watershed Project v. U.S. Forest Service (D. Utah). On June 2, the district court granted the Forest Service’s partial Motion to Dismiss one of several claims challenging the decision to not suspend and cancel grazing on three allotments on the Fishlake National Forest for the 2019 grazing season permits. This case was introduced here.

Unite the Parks v. U.S. Forest Service (E.D. Cal.). On May 28, the district court denied the plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction against 45 forest health projects on the Sierra, Sequoia and Stanislaus National Forests that may affect the Southern Sierra Nevada Pacific fisher. Most of the claims were based on ESA after the fisher was listed as endangered on May 15, 2020. Regarding the long-term benefits to fisher claimed by the agencies (discussed here), the court found little likelihood that plaintiffs could raise serious questions. The Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service received a second notice of intent to sue under ESA on June 10 containing different claims (not linked).

- Attach4_SandraShort_v_FHA_19-285_D_ND_LittleMissouri_Bridge&Road_Recommend

- Attach5_SandraShort_v_FHS_19-285_D_ND_LittleMissouri_Bridge&Road_Order

Short v. Federal Highway Administration (D. N.D). On May 28, the district court dismissed the Forest Service from the case without prejudice, based on their role as a cooperating agency for Little Missouri Crossing Road and Bridge Project that encroaches on and crosses the Little Missouri National Grassland and the Dakota Prairie Grassland (as well as plaintiff’s property).

Center for Biological Diversity v. U.S. Forest Service (D. Idaho). On June 4, the district court upheld the Bog Creek Road Project in the Selkirk Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest, which will reopen the road for administrative use by Customs and Border Protection in monitoring the border with Canada.

MAGISTRATE’S RECOMMENDATION

- Flathead revision/grizzly bear amendments

O’Neil v. Steele (D. Mont.). On June 8, the magistrate judge issued a findings and recommendation favorable to the Forest Service regarding the Flathead National Forest 2018 revised Forest Plan and the Lolo, Helena-Lewis & Clark and Kootenai National Forests amended Forest Plans. These plaintiffs have claimed that the Forest Service did not consider the albedo effect and should have planned for more timber harvest. (No court document was provided.)

NEW CASES

Alliance for The Wild Rockies v. Pierson (D. Idaho). On June 7, the plaintiff filed a complaint against the Forest Service’s October 11, 2018 Decision Memo (DM) and May 28, 2021 Supplemental DM (based on categorical exclusions) approving the Hanna Flats Project on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest. The Supplemental DM was the result of the court’s remand on April 27 to address Wildland-Urban Interface boundaries (described here).

Save the Bull Trout v. U.S. Forest Service (D. Mont.). On June 4, the plaintiffs filed a complaint against the East Fork and Rock Creek Diversion on the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest, alleging violations of the Endangered Species Act resulting from ongoing unpermitted incidental take of bull trout.

NOTICE OF INTENT TO SUE

In a second NOI dated June 4 to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Forest Service (first NOI issued September 13, 2019), the Center for Biological Diversity and Maricopa Audubon Society expressed continued concerns that inadequate exclosure fencing (and monitoring of fencing) has resulted in cattle from two allotments entering protected areas that has resulted in destruction and modification of endangered New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse critical habitat, and other effects not considered in 2021 biological opinions for the allotments.

BLOGGER’S BONUS (links are to news articles)

(Notice of intent.) The Environmental Protection Information Center filed the notice along with the Center for Biological Diversity and the Klamath Siskiyou Wildlands Center on June 2. The NOI states that the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service failed to explain why the West Coast population, which was petitioned for listing by the groups on this notice and found to warrant protection in 2004 and subsequent years, no longer warrants protection as a threatened or endangered species. A final listing rule made in May 2020 revised the West Coast population’s definition into two separate distinct population segments, the previously established Northern-California-Southern Oregon and Southern Sierra Nevada populations and only granting protection to the latter. (See the Unite the Parks case above.)

(Update.) The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said on June 2 it will propose listing the Tiehm’s buckwheat as an endangered species, dealing a blow to ioneer Ltd’s proposed Rhyolite Ridge lithium mine on BLM land in Nevada. This decision is in response to a court-imposed deadline (as discussed here).

(New case.) On June 3, a coalition of conservation groups sued the Department of Interior over the BLM’s decision to allow construction of a new four-lane highway through a national conservation area in southern Utah that includes protected habitat for the Mojave desert tortoise. (The complaint in Conserve Southwest Utah v. USDI is here.)

(Update.) On June 4, the Biden administration announced its intent to rescind or revise several implementing regulations for the Endangered Species Act finalized under the prior administration. This includes the regulations at issue in the ESA litigation described here.

Science Friday: RMRS Lynx and Winter Recreation Study

I’d like to highlight a very useful study that came across my desk, and thank scientists Olson, Squires, Roberts and Ivan, the funders of the research and the person who did this excellent writeup, and, of course, L. Olsen who did the amazing graphics.

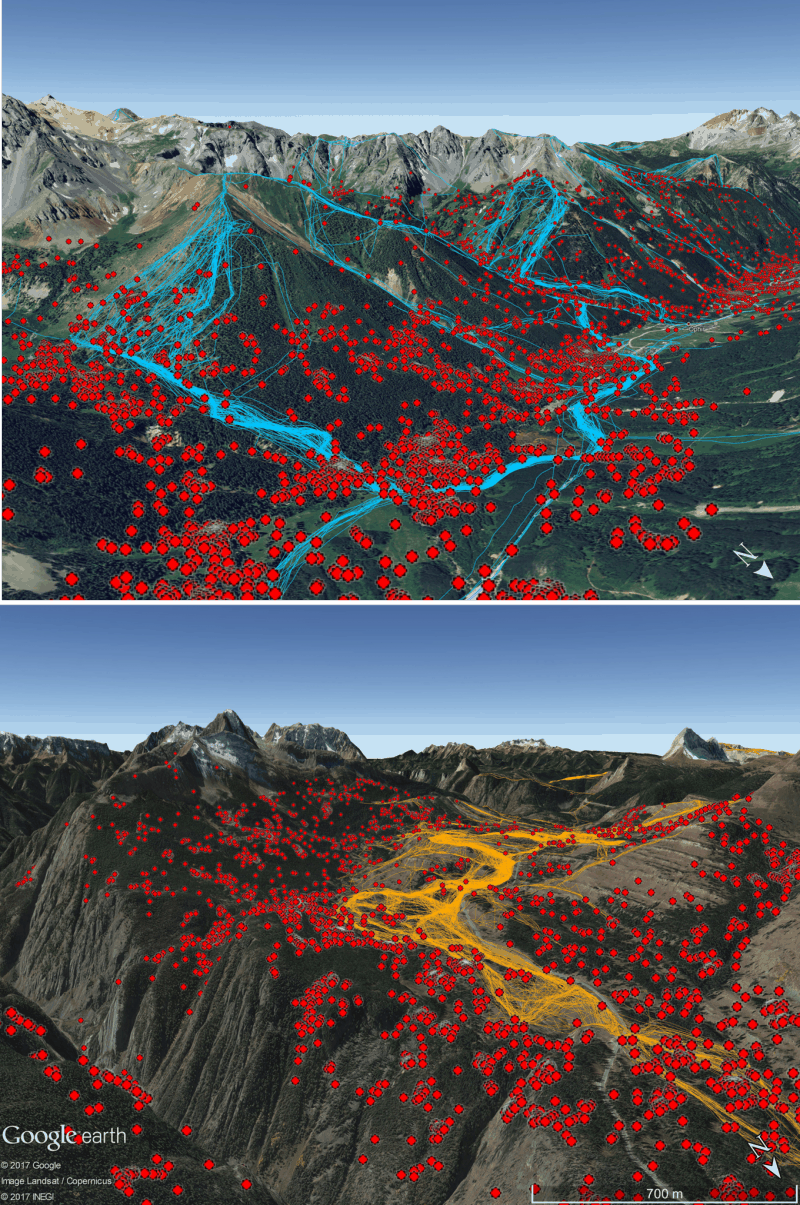

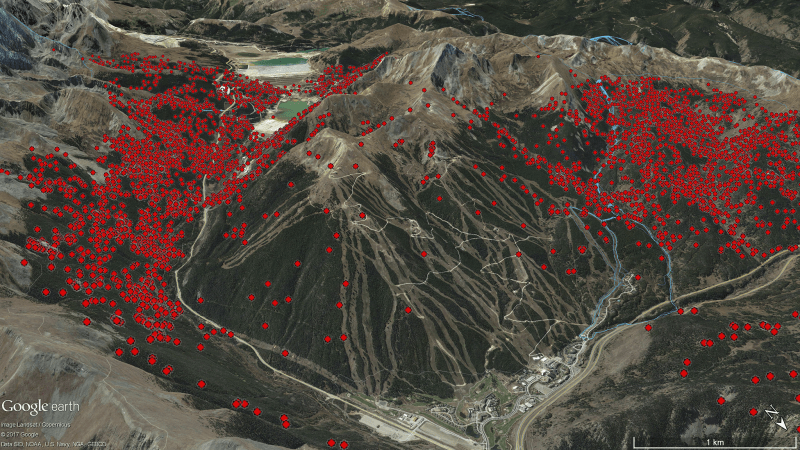

They found that the potential for conflict between lynx and recreationists was lessened by the fact that the lynx, skiers, and snowmobilers divide up the slopes in different ways largely related to the density of forest cover. The use by lynx of areas with dense horizontal forest cover for hunting hares serves to segregate them to some extent from skiers and snowmobilers. Snowmobilers, in particular, are using more open slopes. “We thought snowmobiling might be a big concern, but it seems like lynx aren’t going to be in the areas that they normally use,’ explains Olson. Lynx and skiers, however, appear to share a similar preference for steeper slopes, dense canopy, and patchy forest. Contrary to expectations, however, the researchers found no consistent avoidance of low to moderate-intensity levels of snowmobiling, back country skiing, or packed trail skiing. Lynx exhibited some avoidance of areas with higher levels of motorized recreation and developed ski areas, but not to high-use, backcountry ski trails. “They get a lot of skier traffic on Vail Pass, like the 10th Mountain Division trails that go up to the huts. And there’s no evidence of any avoidance of the immediate trail buffer by lynx,” explains Squires, “They use the area right next to the trail, and they cross the trail, they’re all over the trail. However, despite our study areas including some of the highest levels of winter recreation in North America, Canada lynx and winter recreationists selected different environmental features across landscape that resulted in low overlap with snowmobiling and moderate overlap with backcountry skiing. For example, lynx inhabited forest with higher levels of forest canopy cover than typically used by recreationists. Lynx also modified their behavior in nuanced ways by decreasing their movement rate or increasing time spent not moving, or becoming more active at night, in areas with more high-intensity dispersed recreation.”

KEY FINDINGS

- The GPS tracking data showed that snowmobilers on trails prefer shallow slopes, valley bottoms, and lower canopy cover, while skiers prefer greater canopy cover, steep slopes, and ridges. All types of recreation, however, were driven by presence of snow and access.

- Lynx have different habitat preferences than snowmobilers and so may be unlikely to frequently come into contact with them. Lynx and skiers, however, both prefer steeper slopes, dense canopy, and patchy forest cover.

- Lynx do not appear to be as sensitive to low and moderate levels of skiing and snowmobiling as originally thought; instead, lynx modify their behavior to avoid some types of recreation, but appear to be fairly tolerant of non-motorized (skiing) types of recreation.

- High intensities of winter recreation, such as at developed ski areas, may represent a threshold above which lynx have a difficult time coexisting.

MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS

- Tracking people involved in winter recreation gives important insight into where certain activities may be concentrated, and where the greatest potential is for conflict between motorized and non-motorized types of recreation and people and wildlife.

- Lower levels of dispersed recreation at the intensities seen at these Colorado study areas appears to be compatible with lynx occurrence.

- Lynx appear to have an upper threshold of recreation intensity which they can tolerate, and above this level, lynx may be less able to coexist. Managers, then, should keep in mind that developed or dispersed areas with very high use may displace lynx from habitat.

- Lynx select dense forests with high canopy cover during winter. Forest management that alters tree density could alter how lynx and winter recreationists partition landscapes.

- It is still unclear how recreation affects other aspects of lynx biology, such as ability to successfully den and raise kittens, and this is an area that requires further research.

Forest Service Budget – Chairman of the Senate Interior, Environment and Related Agencies Appropriations Subcommittee.

Speaking again of the Salmon-Challis National Forest’s alleged predicament, that they have to sell trees to be able to afford fuel treatments, this budget proposal from Oregon Senator Merkley might be part of the solution.

“I’m ready to be in partnership with the U.S. Forest Chief,” Merkley said, describing plans to get the federal agency the resources it needs to improve forest management, reduce catastrophic fires and provide greater protection for parts of towns and cities threatened by wildfire in the urban-rural interface.

In Oregon we have more than 2 million acres and we’ve already gone through the environmental process to be approved to be treated, and yet we don’t have the money to actually do the treatment,” he said.

Merkley said he’s spoken with the Biden Administration about “viewing our national forest as infrastructure,” and wants the president to add forest management commitments in Biden’s infrastructure proposal known as the American Jobs Plan.

He also says that news of the president’s “commitment” to the forest management program could be days away. (This was May 28; did I miss it?)

I wasn’t aware that the legislation intended to end fire borrowing may have failed:

A “Wildfire Suppression Cap Adjustment” emergency fund that the forest service could dip into during “bad fire years” was enacted in 2018 by the Senate appropriations committee, but the fund conflicts with the 10-year budgets required by the Budget Control Act of 2011.

Merkley also proposes “offering forest management jobs to wildland firefighters.”

Where should fire suppression be a “fact of life?”

Sharon referred to “where fire suppression is a fact of life.” I referred to the planning question of identifying where those areas are. It seems to me that would be either where fires won’t ever occur (hard to imagine), or where they can’t be allowed to burn. The reason in the latter case would depend on some kind of values at risk. I continue to be amazed at how unwilling the Forest Service is to attack this problem from that direction – minimizing the values at risk in areas that are likely to burn. In particular, their engagement (or lack thereof) with local community planning for developments and infrastructure. And there are other reasons besides fire risk, in particular fragmentation of wildlife habitat that reduces connectivity.

Any way, here is an example from the Croatan National Forest.

The 2002 Croatan National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan stated that around 70 percent of the Croatan is home to short interval fire-adapted ecosystems—like pine trees and pocosins.

Low-intensity, prescribed fires allows nutrient cycling to occur. Without them, the entire structure and composition of species are subject to change.

“These are fire-maintained habitats, without prescribed burnings, it is like trying to save a salt marsh without the tide,” said Fussell.

Longleaf pine restoration is especially dependent on prescribed fires as the exposed soil helps the seeds to germinate and they control the population of competing pine variations.

Prescribed burning is harder to do the more fragmented an ecosystem is and the closer it gets to development. Because it is harder to burn in smaller areas, prescribed burnings have decreased in recent years, said Fussell.

The Forest Service has a legal imperative to NOT allow the structure and composition of species to change. Where adjacent development has already occurred, fire suppression is probably going to be a “fact of life,” but that fact should be motivating the Forest Service to participate in local planning to encourage future development consistent with the fire regime on the adjacent national forest. It’s difficult to understand why no one from the Forest Service was interviewed for this article, since they should be on the forefront of these kinds of discussions. (They evidently did get involved in some highway planning in order to continue prescribed burning, which at least suggests they recognize the problem.)

This article cites some research that reiterates the findings of the Forest Service “Forest on the Edge” program (which I contributed to along the way).

By 2030, a study from 2009 by researchers at the University of Wisconsin and other industry professionals, projects that 16 million new housing units will be built around national forests across the United States. A projected 662,000 will be built in national forests.

“New houses will remove and fragment habitats, diminish water quality, foster the spread of invasive species and decrease biodiversity,” stated the study.

This is happening everywhere, and the Forest Service needs to be more assertive in trying to minimize the areas “where fire suppression is a fact of life.”

New Forest Service plan revision strategy – not doing it

Speaking of the Salmon-Challis and its forest supervisor, I was also reminded by this article of his novel approach to revising the Salmon and Challis national forest plans, which could mean not revising them. Now it appears that the regional forester (Farnsworth) is actually considering that option.

Given the choice between full revision, amended revision or no revision of the two plans, commissioners Butts and Smith said full revision is the least desirable option.

Butts and Smith said they’re concerned a full revision won’t prioritize local stakeholders’ perspectives or address their specific needs. Fearing pressure from environmental groups who don’t live near the forest using lawsuits against the Forest Service to control what happens to it, the commissioners said they worry the most about losing multi-use land stewardship in the forest to wilderness and scenic river designations.

Reaffirming the revision process is about getting the national forest in line with current policies, not the Forest Service caving to legal pressures, Farnsworth told the commissioners she will look at the letters they have sent before rendering a decision. “I’ll make this call, one way or another, because we have to stop the bantering,” Farnsworth said.

My understanding is that the Forest Service is not given that choice, and there is only one call that can be made, and it is misleading the public to suggest otherwise. NFMA requires that forest plans be revised at least every 15 years. These forests should have revised their plans by 2002. Congress has given the Forest Service extensions through appropriations riders as long as they are making reasonable progress. There is no legal option of amending plans instead of revising them, or just keeping them in place forever. Even further delay can’t be justified at this point, especially where these are the kinds of reasons. While the requirement for plan revision doesn’t necessarily mean a plan has to be changed, it does require going through the revision process to readopt the existing plan, with full public involvement. Maybe that’s what they have in mind …