Below is the press release. Should rare and recovering native wildlife be given priority on federal public lands? Or should the demands of those who pay $1.35/month per 5 sheep to grazing their non-native domestic sheep destined for slaughter be given priority on public lands?

SPOKANE, WA—Two environmental groups filed a lawsuit in federal court Monday claiming the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest is placing bighorn sheep at high risk of disease outbreaks by authorizing domestic sheep grazing in the vicinity of bighorn herds. The suit, brought by WildEarth Guardians and Western Watersheds Project, asserts that the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest has known of the high risk that domestic sheep grazing poses to bighorn sheep for at least a decade, yet has authorized grazing anyway.

“The Forest Service has known about the high risk to bighorns in this area for over a decade and has refused to take action. We have pleaded with them for years to do something, yet they have just sat by as bighorns died. If the agency tasked with protecting this iconic species won’t do so, we’re here to make sure they do,” said Greg Dyson of WildEarth Guardians.

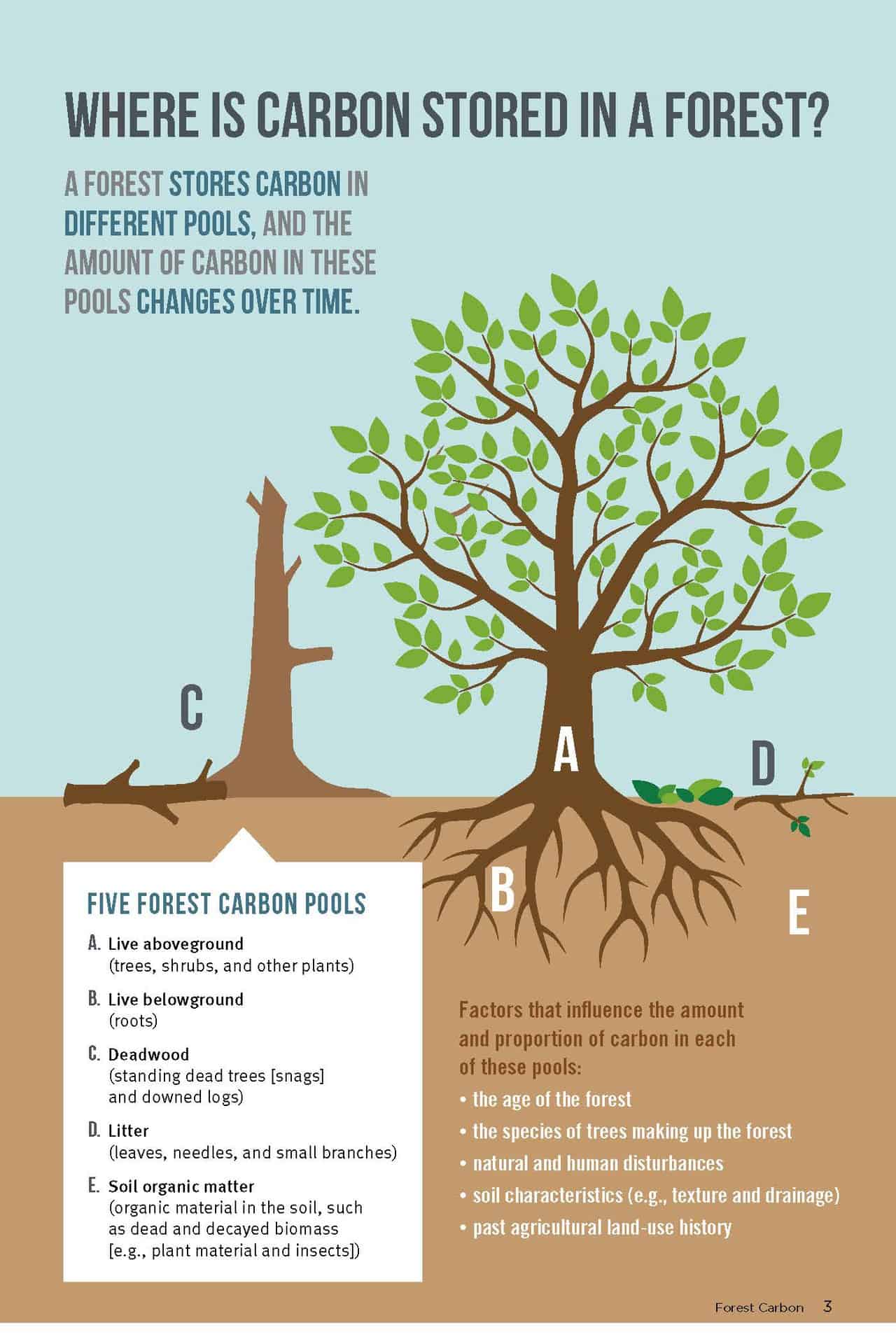

Domestic sheep carry a pathogen that, when transmitted to bighorn sheep, causes deadly pneumonia in bighorns and reduces lamb survival rates for years. The pathogen—known as Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae—is especially deadly because bighorns and domestic sheep are mutually attracted to each other. Once disease is in a bighorn herd, it can cause low lamb survival for a decade, and members of that herd can easily transmit the disease to nearby bighorn herds. There is no cure or vaccine.

“The science is overwhelmingly clear that the biggest risk to bighorn health is the diseases spread by domestic sheep grazing in and near bighorn habitat,” said Melissa Cain of Western Watersheds Project. “There have been two disease-related incidents in these bighorn herds in recent months. In October, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) killed 12 bighorns from the Quilomene herd due to a domestic ewe commingling with the herd. Less than 2 weeks later, WDFW reported Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae within the Cleman Mountain herd. It is not acceptable for the Forest Service to knowingly allow the high risk to continue.

See the WDFW website for details on the two recent incidents (here, here and here).

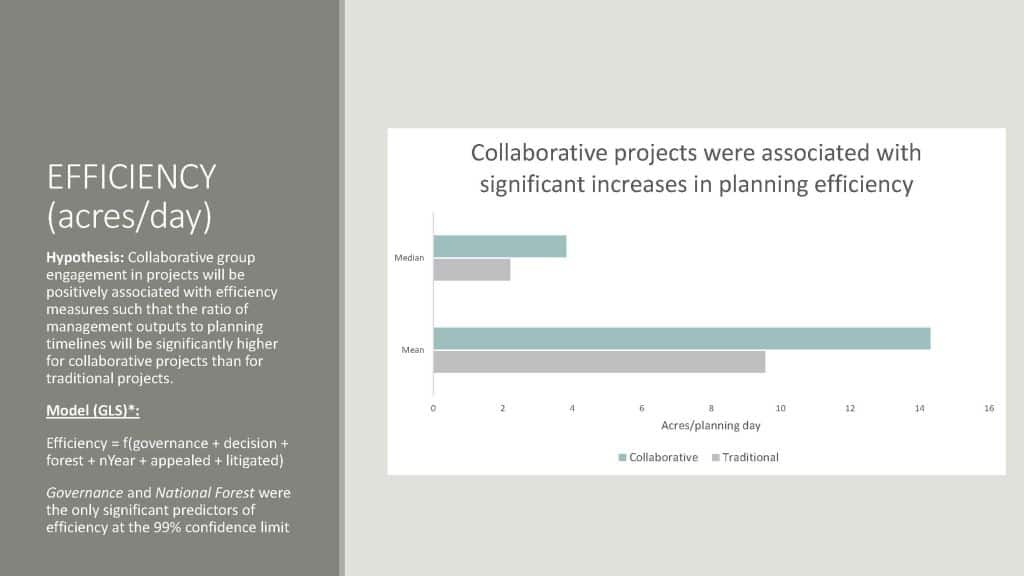

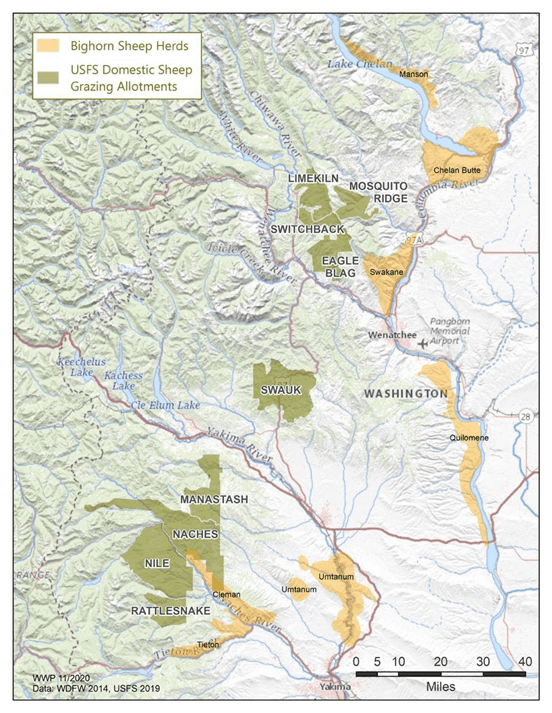

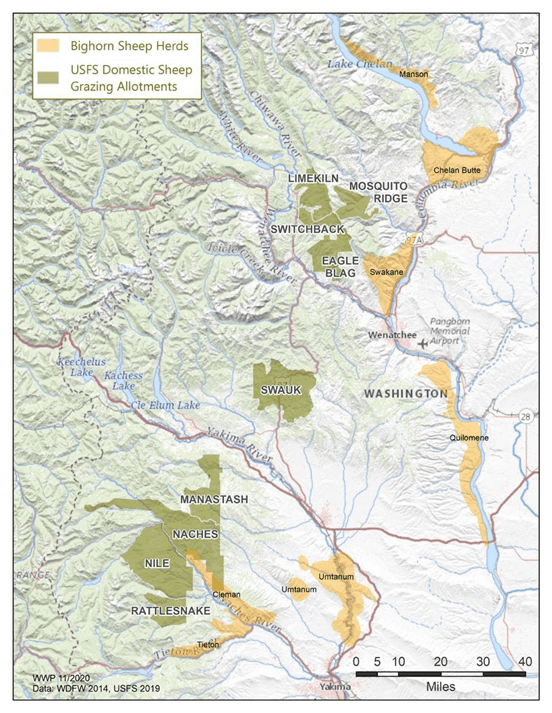

Today’s suit centers on seven domestic sheep allotments near the eastern boundary of the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. The Forest Service conducted a risk analysis in 2016 determining that these allotments place four bighorn herds at high risk: the Umtanum, Swakane, Cleman Mountain, and Chelan Butte herds.

The lawsuit alleges that the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest continued to authorize domestic sheep grazing despite knowing about the high risk to bighorns as far back as 2010. In addition, the four bighorn herds placed at high risk by the Forest Service’s actions are within 15 miles of each other and two other bighorn herds—the Quilomene and Manson herds—meaning that individual bighorns could easily foray between herds, further spreading disease picked up from the domestic sheep. Together, these bighorn herds make up over half of Washington’s total bighorn sheep population. Another bighorn herd, the Tieton herd, had occupied habitat that was adjacent to these domestic sheep allotments until it suffered a severe outbreak of pneumonia in 2013, which WDFW determined was caused by domestic sheep and led to all 200 of the bighorns in this herd being eradicated.

“The Forest Service is well aware of its legal duties—under the National Forest Management Act and the Wenatchee National Forest Plan—to prevent domestic sheep grazing on public lands from transmitting disease to bighorn sheep. For years, as problems mounted for bighorns, the agency has disregarded these legal duties by authorizing thousands of domestic sheep to graze on high-risk allotments each summer,” stated Lizzy Potter, lead attorney on the case. “We filed suit to hold the Forest Service accountable for these egregious legal violations and to protect half of the bighorn sheep in Washington state.”

Bighorn sheep were wiped out during the era of Western settlement, as Old World pathogens carried by domestic sheep were transmitted to native bighorn sheep. By the early 1900s, bighorns had vanished from several states, with only a few thousand remaining from an estimated historic population of 1.5 to 2 million. Following more than six decades of extensive and costly restoration efforts, bighorn sheep have now been recovered to approximately 5% of their historic population levels and roughly 10% of their historic range.

The groups are represented in the litigation by Lizzy Potter and Laurie Rule of Advocates for the West.