This is sort of a counterpoint post to the one below about “Renewable Energy on Federal Lands.” Consider it an example of “Non-Renewable Energy on Federal Lands.” It’s a press release from a coalition of Tribal, grassroots, environmental and public health advocates.

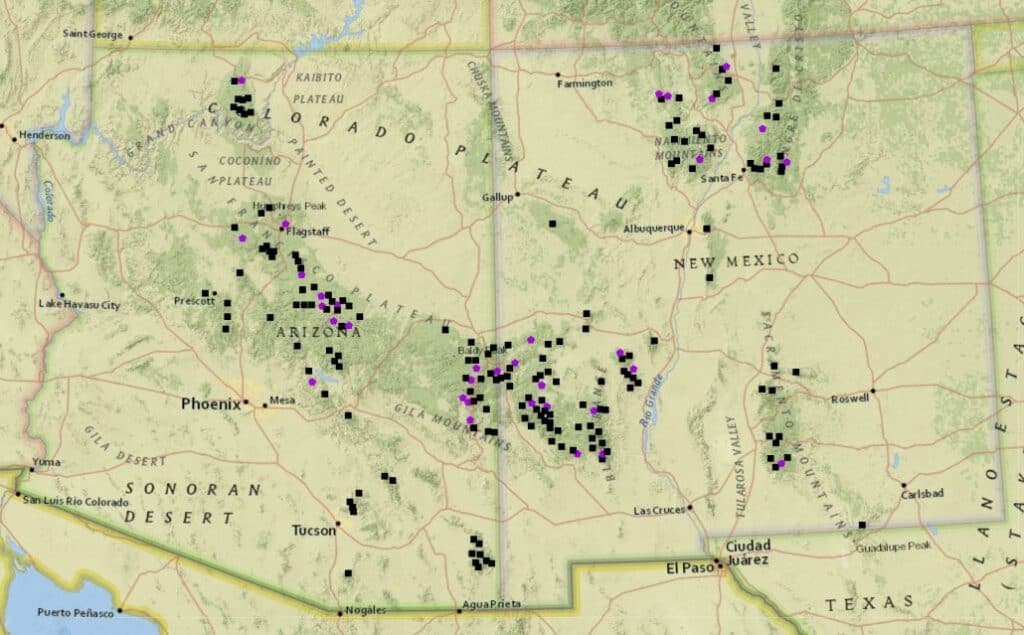

Santa Fe, NM–A coalition of Tribal, grassroots, and environmental and health advocates today filed suit to overturn the sale of nearly 41,000 acres of public lands in the Greater Chaco region of northwest New Mexico for fracking.

In a complaint filed in federal court, Diné Citizens Against Ruining Our Environment, WildEarth Guardians, San Juan Citizens Alliance, the Sierra Club, and the Western Environmental Law Center confronted the Trump administration’s disregard for health, environmental justice, and the climate. The case challenges a December 2018 sale of public lands for fracking in northwest Sandoval County, which is part of the Greater Chaco region of New Mexico.

“This lease sale will have a direct impact on the Diné communities of Ojo Encino, Torreon and others,” said Wendy Atcitty with Diné C.A.R.E. “Within the nearly 41,000 acres of lease sale parcels are four to five municipal wells that provide water to Ojo Encino, Torreon, Pueblo Pintado, and White Horse Lake. So far, the Bureau has failed to address health concerns, air and water quality concerns, or provide opportunities for meaningful public participation in this whole process. The health of our communities needs to come first.”

In spite of its cultural significance, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management has approved hundreds of new oil and gas wells in the region, many near Chaco Culture National Historical Park. Even after a federal appeals court held in 2019 that the Bureau illegally approved hundreds of drilling permits, the Bureau has continued to approve more fracking.

“The Bureau of Land Management continues to run roughshod over the Greater Chaco landscape by sanctioning an unprecedented amount of industrialized fracking having never analyzed the impacts of these activities on communities or the climate,” said Rebecca Sobel with WildEarth Guardians. “In the midst of a pandemic, we are forced back to court to defend Diné communities that continue to suffer from oil and gas impacts and related COVID-19 morbidity–more victims of the administration’s ‘energy dominance’ agenda.”

Today’s lawsuit targets the sale of lands for fracking in northwest Sandoval County, which is part of the Bureau of Land Management’s Rio Puerco Field Office. The suit challenges the failure of the Bureau to address the health, climate, and environmental justice impacts of fracking in the Greater Chaco region.

The Bureau of Land Management sidestepped its public involvement process and also failed to take a hard look at environmental justice impacts. The Bureau also failed to adequately analyze the effects of oil and gas drilling on the health of nearby residents. The agency ignored the disproportionate health and safety risks of fracking and drilling–especially cumulative impacts–to Navajo people and communities in the lease sale area.

“It is both unethical and unlawful for the agency to ignore the inequities and injustices inherent to its oil and gas program,” said Ally Beasley with the Western Environmental Law Center. “These inequities and injustices are not incidental–they are structural, systemic, and part of a historical, ongoing pattern and practice of environmental racism, colonialism, and treatment of the Greater Chaco as an energy sacrifice zone. It has to stop.”

The suit also targets the fact that the management plan for the Rio Puerco Field Office, which was adopted in 1986, never authorized fracking. In 2019, a coalition called on the Bureau of Land Management to halt the sale of lands for fracking in the Field Office. The agency never responded.

“The Bureau continues irresponsible oil and gas leasing that cuts out public participation and any comprehensive analysis of what would transpire on the landscape and in communities when oil and gas development would occur,” said Mike Eisenfeld of San Juan Citizens Alliance. “We appreciate the commitment of organizations associated with this litigation to address inequities and agency indifference to upholding their responsibilities.”

“Today’s filing underscores the need to hold to account the Trump administration’s Bureau of Land Management for its repeated illegal actions that bypass thorough environmental reviews and cultural resource assessments, ignore public input, and sideline meaningful Tribal consultation in its oil and gas leasing program,” said Miya King-Flaherty with the Sierra Club – Rio Grande Chapter. “The Greater Chaco landscape continues to be desecrated, and the environmental injustices perpetrated in this region must stop.”

A 2018 U.S. Geological Survey report found that oil and gas produced from public lands and waters contributes to 10 percent of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. And a 2018 report by the Stockholm Environmental Institute confirmed that ending public lands fossil fuel production could significantly reduce nationwide greenhouse gas emissions.

Ending the sale of public lands for fracking would also yield enormous health benefits. In addition to the industry’s climate impacts, the fracking science compendium released in June 2019 by Physicians for Social Responsibility and Concerned Health Professionals of New York confirmed extensive health risks associated with oil and gas extraction, including cancer, asthma, pre-term birth, and more.