The “real thing” is back (with a vengeance). This is why I try to not get too far ahead of the Forest Service. This FS litigation “weekly” covers six of them, some of which I’ve already addressed, so I guess you’ll get them twice. The full Forest Service summaries for all may be found here:

Litigation Weekly June 5_2020_EMAIL

I’m also just copying their shorter email summary here and providing links to the related documents provided by the Forest Service, as well as to any previous summaries and a few related articles.

COURT DECISIONS

On April 20, 2020, the District Court of Montana issued an order lifting the injunction on the Bozeman Municipal Watershed Fuels Reduction Project and the East Boulder Fuel Reduction Project on the Gallatin National Forest after the Forest Service adequately assessed the impacts of the Northern Rockies Lynx Amendment (Lynx Amendment) and the projects on the Canada Lynx and its critical habitat. The projects aimed to reduce the severity and collateral effects of wildfire by way of logging, thinning, and prescribed burns. Both projects were to take place in areas designated as critical habitat lynx. (Previously summarized here.)

On April 21, 2020, the Eastern District Court of California issued an order dismissing the plaintiffs motions for temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction concerning the use of disaster relief funds for clearcutting timber, and construction of new biomass power plant utilizing the timber as feedstock following the 2013 Rim Fire on the Stanislaus National Forest. (Previously summarized here.)

On April 29, 2020, the District Court of Montana issued an order favorable to the Forest Service dismissing the plaintiff’s motion for Temporary Restraining Order (TRO) and Preliminary Injunction regarding the Darby Lumber Lands Project on the Bitterroot National Forest. (Previously summarized here.)

On May 7, 2020, the District Court of Idaho issued an order that granted the Forest Service’s motion to dismiss the plaintiffs’ claim that the Agency supplement the 1995 Environmental Assessment (EA) based on new information. However, the district denied the Forest Service’s and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s motion to dismiss the plaintiffs’ claim for reinitiating consultation based on taking of grizzly bear resulting from black-bear baiting for hunting in the Idaho Panhandle National Forest, Caribou-Targhee, Bridger-Teton, and Shoshone National Forests. (Previously summarized here.)

On May 4, 2020, the District Court of Idaho issued a decision concerning the Kilgore Exploration Project on the Caribou-Targhee National Forest (a 5-year mining exploration project). The court vacated the August 20, 2018, decision notice (DN) and finding of no significant impact (FONSI) and the environmental assessment (EA). The district court’s December 18, 2019 decision had permitted the project to proceed, minus the Dog Bone Ridge portion of the project. (Previously summarized here.)

May 1, 2020, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the Forest Service upholding the District Court of Oregon’s decision granting summary judgment for the Forest Service, concerning the plaintiffs’ challenge to the issuance of grazing authorizations between 2006 and 2015 on seven grazing allotments on the Malheur National Forest. The plaintiffs allege non-compliance with the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (WSRA), Administrative Procedures Act (APA), National Forest Management Act (NFMA), and Inland Native Fish Strategy (INFISH). (Previously summarized here.)

On May 8, 2020, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the District Court for Eastern California’s favorable decision to the Forest Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) concerning the Bagley Hazard Tree Abatement Project on the Trinity National Forest. (Previously summarized here.)

On May 20, 2020, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the District Court of Idaho’s favorable decision to the Forest Service, concerning the Windy Shingle Project on the Perce Clearwater National Forest. The project was approved with an insect and disease categorical exclusion (CE), under the 2014 amended Healthy Forest Restoration Act (HFRA), sections 602 and 603. The Forest completed an extraordinary circumstances analysis and evaluated the cumulative impacts. The 9th Circuit found that the methods applied for determining old growth status were legitimate, and that adjusting the management areas was permitted by the Nez Perce Forest Plan.

On May 26, 2020, the District Court of Central California issued a decision favorable to the Forest Service concerning the Cuddy Valley Project on the Los Padres National Forest involving the use of a 36 C.F.R. § 220.6(e)(6) categorical exclusion (CE), for timber stand and wildlife habitat improvement. The plaintiffs asserted that approval of the project violated the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), National Forest Management Act (NFMA), and Administrative Procedures Act (APA).

On May 28, 2020, the Court of Federal Claims issued an order dismissing the case for lack of jurisdiction in favor of the National Park Service and the Forest Service concerning continued allowance of the hunting of bison that have migrated out of the Yellowstone National Park and through Beattie Gulch on the Custer-Gallatin National Forest. Plaintiffs allege the hunting program has affected a temporary regulatory taking of plaintiffs’ property by creating an atmosphere of danger and decreasing the rental value of their property.

On May 28, 2020, the District Court of Eastern California issued a decision against the Forest Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) concerning the Pettijon Project (a fuel-reduction project) on the Shasta-Trinity National Forest regarding the Plaintiffs motion to supplement the administrative record.

On May 22, 2020, the District Court of Arizona issued an order in favor of the Forest Service concerning the remaining claim which challenged the Agency’s determination that Energy Fuels has “valid existing rights” (VER) at the Canyon Mine on the Kaibab National Forest. The Decision concerns the district court evaluation of Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) in determining prior existing rights based on the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals order (December 19, 2019) vacating back to the lower court for review. (More in this article.)

On May 26, 2020, the District Court of Montana issued a decision favorable to the Forest Service, concerning Robbins Gulch Road easement on the Bitterroot National Forest. The court granted the Agency’s motion to dismiss and denied the plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment. The plaintiffs alleged that by allowing public access on Robbins Gulch Road, the Forest Service was exceeding the scope of its 1962 road easement, which plaintiffs argued was limited to Forest Service use only, such as for timber or grazing purposes, and was not intended to provide public access to National Forest System lands. (More in this article.)

COURT UPDATE

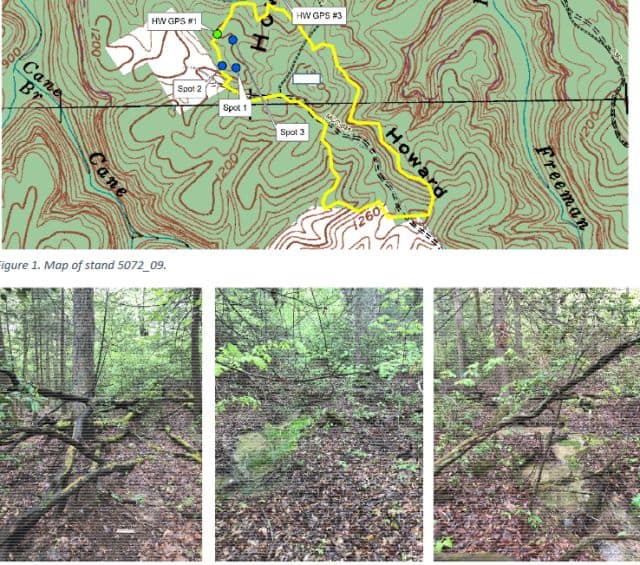

On April 24, 2020, the District Court of Montana issued an order regarding a factual dispute between the Forest Service and the plaintiff, which must be addressed prior to summary judgement. The case concerns the Forest Service’s approval of Tenmile South-Helena Vegetation Project on the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest. A factual dispute arose after the plaintiffs took photos and collected GPS information in the project area, which they believe strengthens their case.

NEW CASES

On April 20, 2020, the plaintiffs filed a complaint in the District Court of Oregon against the Forest Service concerning the Black Mountain Vegetation Management Project on the Ochoco National Forest. Plaintiffs claim the project is inconsistent with the Ochoco NF Forest Plan as amended by Inland Native Fish Strategy (INFISH). The plaintiffs claim the Forest Service failed to take a hard look at direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts of the project. (Introduced here.)

On April 20, 2020, the plaintiffs filed a complaint against the Forest Service concerning the Crow Creek Pipeline on the Caribou-Targhee National Forest and the Agency’s final decision and amendments to the 2003 Caribou-Targhee National Forest (CTNF) Forest Plan. The plaintiffs allege violations of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), National Forest Management Act (NFMA), Mineral Leasing (MLA), and National Trails System Act (NTSA). (Introduced here.)

On April 20, 2020, the plaintiffs filed a complaint in the District Court of Wyoming against the Forest Service approval of the Alkali Creek, Forest Park, and Dell Creek feedgrounds on the Bridger-Teton National Forest. The plaintiffs challenge two feedground decisions by the Forest Service’s (1) five year approval of the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission request to resume feeding operations on the Alkali Creek Feedground without conducting the environmental analysis previously ordered by the district court (September 14, 2019 order; 17-0202, D. Wyo.); and (2) indefinite authorization of artificial feeding at Dell Creek and Forest Park feedgrounds without issuing the special uses permit under the Forest Service’s own regulations (36 CFR section 251.54(e)(1), or conducting environmental analysis under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). (Introduced here.)

April 27, 2020, the petitioner (YJ Guide Service, LLC dba Bungalow Outfitters) a hunting outfitter and guide, filed an application for Temporary Restraining Order (TRO) in the District Court of Idaho against the Forest Service regarding suspension of a special use permit for Outfitting and Guiding on the North Fork Ranger District of the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest. No complaint has yet been filed. The petitioner’s application for the TRO is based on upon grounds that it believes it will suffer irreparable harm and injury if the TRO is not issued.

On April 24, 2020, the plaintiffs filed a complaint in the Eastern District of California against the Forest Service concerning the Crawford Vegetation Project on the Klamath National Forest. The plaintiffs claim the Forest Service failed to supplement their environmental analysis for the project in light of significant new information and changed circumstances regarding the impacts of the project on the northern spotted owl and Pacific fisher which have been found in the project area.

On May 6, 2020, the plaintiffs filed a complaint in the District Court for the District of Columbia against the U.S. Department of Interior (DOI), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Forest Service concerning compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) when the BLM issued two hard-rock mining lease renewals to Twin Metals Minnesota in an area adjacent to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (Boundary Waters) on the Superior National Forest. (This latest lawsuit was introduced here.)

On May 7, 2020, the plaintiffs filed a complaint in the District Court of Idaho against the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) concerning their predator damage management actions in the State of Idaho, relying on inadequate and outdated environmental analysis in violation of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The plaintiffs bring related claims against the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and Forest Service, which authorized APHIS’s aerial gunning of coyotes and other wildlife on federal lands [through Annual Work Plans (AWPs)], without adequate environmental analysis in violation of NEPA.

On May 8, 2020, the plaintiffs filed a request for a preliminary injunction (PI) in the District Court for the District of Columbia against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the Forest Service concerning the Upper Green River Area Rangeland Project on the Bridger Teton National Forest, which plaintiffs allege unlawfully impacts the grizzly bear, and the Kendall Warm Springs dace. Plaintiffs challenge the FWS issuance of, and the Forest Service reliance on, a flawed Biological Opinion (BO) regarding the negative impacts to grizzly bears that arise from the Forest Service’s authorization of continued livestock grazing in prime grizzly bear habitat within the Forest, in violation of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and Administrative Procedures Act (APA), and impacts on the Kendall Warm Springs dace. (Some prior history can be found here.)

On May 13, 2020, the plaintiffs filed a complaint in the District Court of Indiana against the Forest Service concerning the Forest Service Houston South Vegetation Management and Restoration Project on the Hoosier National Forest. The plaintiffs allege the project violates the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), National Forest Management Act (NFMA), and Administrative Procedures Act (APA). The plaintiff’s concerns are related to the impacts of the project on Lake Monroe watershed, which supplies drinking water for more than 145,000 people. The plaintiffs claim the Forest Service’s action fails to comport with the Agency’s own stated goal of protecting and restoring watershed health in its 2006 Hoosier NF Forest Plan. The project consists of commercial logging, including clear-cuts, shelterwood cuts, selective cuts, and thinning cuts, as well as road building, herbicide application, and prescribed burning activities. (Introduced here.)

On May 20, 2020, the plaintiffs filed a complaint in the District Court of Idaho against the Forest Service for violations of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Endangered Species Act (ESA), National Forest Management Act (NFMA), the Administrative Procedures Act (APA), and Agency Wild and Scenic River regulations concerning the Brebner Flat Project on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest.

NOTICES OF INTENT

On April 15, 2020, (dated April 7, 2020), a 60-day Notice of Intent was received by the Friends of the Clearwater and the Alliance for the Wild Rockies (FOC/AWR) to sue the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the Forest Service concerning the approval of the Lolo Insect and Disease Project and 24 new culvert replacements on the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest. The FOC/AWR state the Forest Service approved a decision permitting the Lolo Insect and Disease Project and 24 culvert replacements, and NMFS’s issued Biological Opinion (BO) and Incidental Take Statement (ITS) for the project on June 20, 2019, and a revised ITS on July 19, 2019, with a take limit of 79 Snake River Basin (SRB) steelhead. The complainants claim violations of Section 7 and Section 9 of the ESA concerning the Snake River Basin Steelhead.

On April 1, 2020, Range 6-received a 60-day Notice of Intent by the WildEarth Guardians (WEG) to sue the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the Forest Service concerning ongoing Livestock Grazing, on the Cooper Mires, Lambert, and C.C. Mountain allotments on the Colville National Forest. The FWS and the Forest Service continue to violate the Endangered Species Act (ESA) section 7 consultation. Complainants claim four listed species and two critical habitats exists within the allotments: bull trout, woodland caribou and their critical habitats, grizzly bear, and Canada lynx. Also, suitable habitat for yellow-billed cuckoo (listed threatened species) and both wolverine and white bark pine are present (candidate species).

NOI-dated April 27, 2019, Alliance for the Wild Rockies and Native Ecosystems Council sent a 60-day Notice of Intent to Sue pursuant to the Endangered Species Act (ESA) for alleged violations concerning the Stonewall Vegetation Project on the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest. The Stonewall project was authorized 1,381 acres of vegetation treatments in a Record of Decision on December 19, 2019. This project was analyzed in a Supplemental EIS due to a fire that had burned through the project area.

NOI-dated May 20, 2020, Center For Biological Diversity, Northeastern Minnesotans for Wilderness and the Wilderness Society sent a 60-day Notice of Intent to Sue the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Forest Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) pursuant to the Endangered Species Act (ESA) for alleged violations concerning BLM’s May 1, 2020 Decision approving Federal Hardrock Prospecting Permit Extensions for Twin Metals; and for the Forest Service and FWS failure to reinitiate and complete ESA consultation regarding ongoing impacts to Federally listed species and their critical habitat from the Prospecting Permits on the Superior National Forest (Region 9). The NOI states that the permits violate Sections 7 and 9 of the ESA based on new information concerning Canada lynx, gray wolf and their critical habitat, and the Northern long-eared bat.