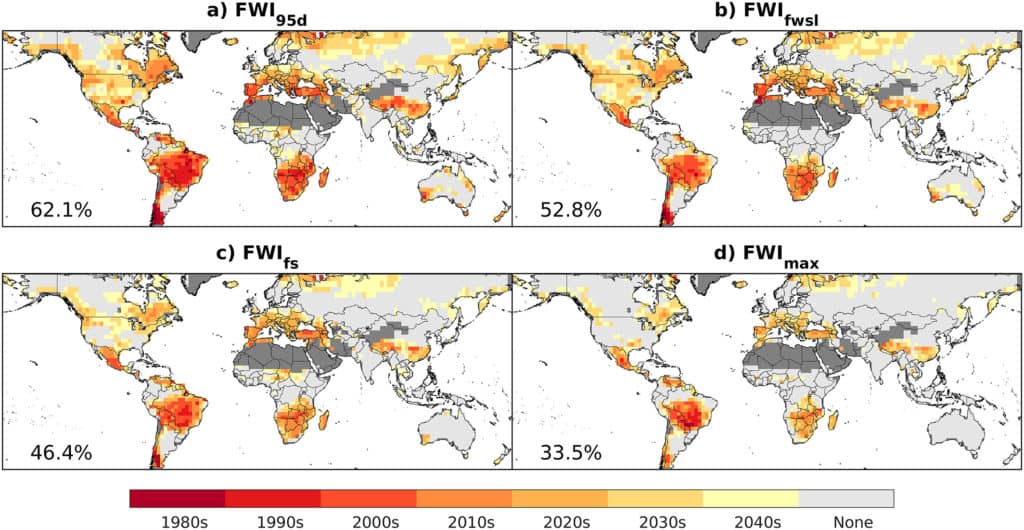

The above maps are from this paper by Abatzoglou et al.

Here’s a link to a Science Brief from the University of East Anglia about climate and wildfires. It’s kind of like a scientific rapid response team when an issue comes up, which made it easy to compare the Western US and Australia in terms of ACC.

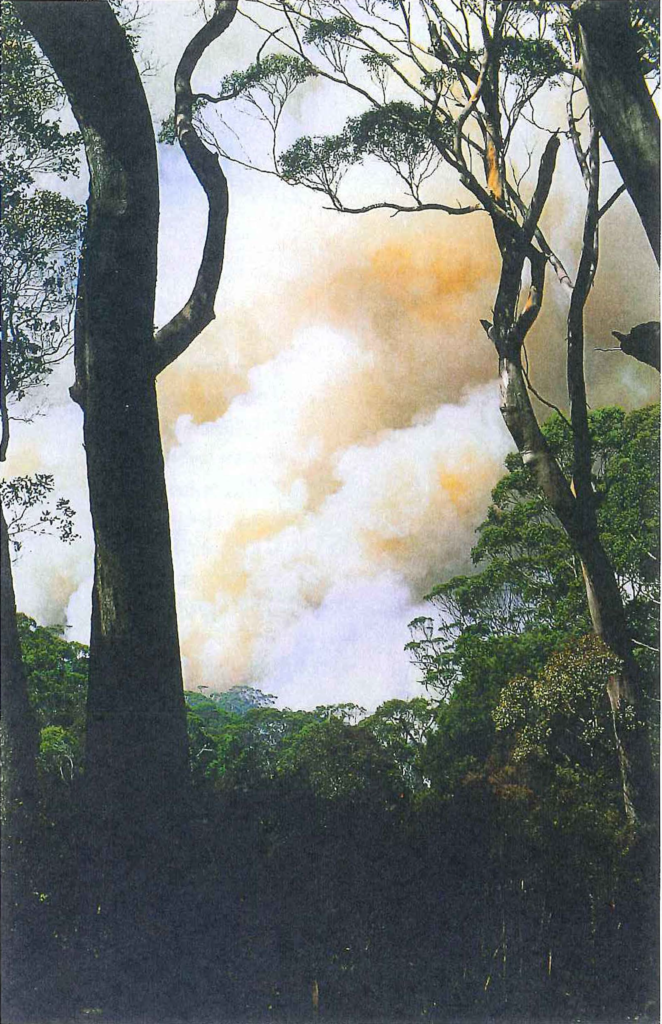

First, here’s Australia

Climate change also affects fire weather in many other regions, although formal detection does not yet emerge from natural variability. Abatzoglou et al. (2019) suggest that the anthropogenic climate change signal will be detectable on 33-62% of the burnable land area by 2050. Other global studies agree that the effect of climate change is to increase fire weather and burned area once other factors have been controlled for (e.g. Huang et al., 2015; Flannigan et al., 2013). Regional modelling studies corroborate these global findings by projecting how climate change will affect fire weather:…

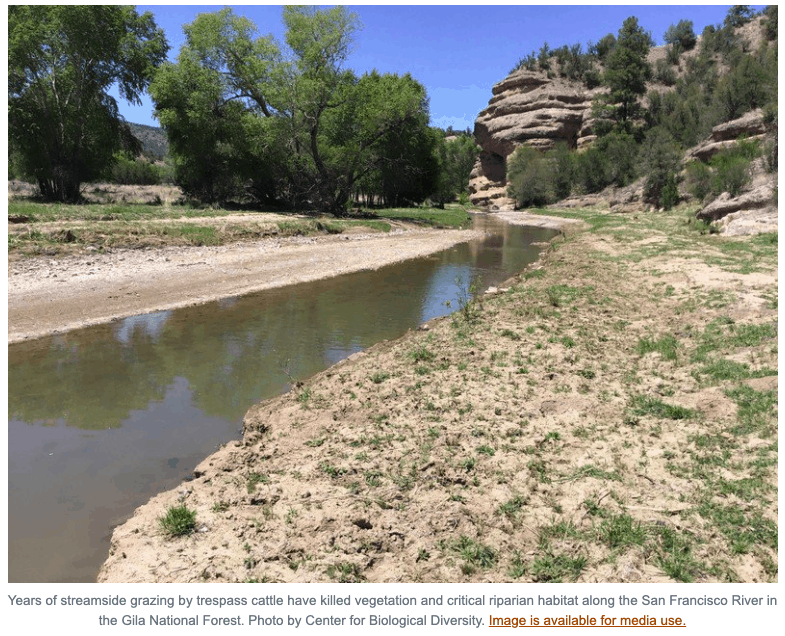

Australia. Observational data suggest that fire weather extremes are already becoming more frequent and intense (Dowdy, 2018; Head et al., 2014). However, the divergence between anthropogenic and natural forcing signals is weaker, and more challenging to diagnose, than in other regions due to strong regional and inter-annual variability in the effect of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation on fire weather (Dowdy, 2018; Sharples et al. , 2016). Other important regional weather patterns, such as the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) also contribute to natural variability in fire weather, but their effects are increasingly superimposed on more favourable background fire weather conditions. Impacts of anthropogenic climate change on fire weather extremes and fire season length are projected to emerge above natural variability in the 2040s (Abatzoglou etal., 2019)

Then here’s the western US:

The impact of anthropogenic climate change on fire weather is emerging above natural variability. Jolly et al. (2015) use observational data to show that fire weather seasons have lengthened across ~25% of the Earth’s vegetated surface, resulting in a ~20% increase in global mean fire weather season length. By 2019, models suggest that the impact of anthropogenic climate change on fire weather was detectable outside the range of natural variability in 22% of global burnable land area (Abatzoglou et al., 2019). Regional studies corroborate these global findings by identifying links between climate change and fire weather, including in the following regions with major recent wildfire outbreaks:…

Western US and Canada. Models suggest that the impacts of anthropogenic climate change on fire weather extremes and fire season length emerged in the 2010s (Abatzoglou et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2019; Abatzoglou & Williams, 2016). Yoon et al. (2015) similarly predicted the occurrence of extreme fire risk would exceed natural variability in California by 2020. Kirchmeir-Young et al. (2017) found that the 2016 Fort McMurray fires were 1.5 to 6 times more likely due to anthropogenic climate change, compared to natural forcing alone. Westerling et al. (2016) found that burned area was >10 times greater in Western US forests in 2003-2012 than in 1973-1982. The 2015 Alaskan wildfires occurred amidst fire weather conditions that were 34-60% more likely due to anthropogenic climate change (Partain et al., 2016).

Note that the claims are sometimes models and sometimes empirical. For example, the increase in burned area noted by Westerling may have had many reasons besides changes in fire weather.

If we accept the Australian claim at face value (differences due to anthropogenic climate change expected to show up in the 2040’s) then they have some time to get their prescribed burning and other programs up to speed before the additional problems due to ACC surface. In that case, it looks like they have about 20 years before they get the additional problems due to ACC. However, if climate modelers don’t understand the natural cycles or anthropogenic factors well enough, though, as seems likely, conditions could be worse sooner or later than the 2040’s. So the Aussies and us, despite the difference in model predictions both need to get on with prescribed burning, building and community design, improving suppression and all that.

As the authors state:

Nonetheless, wildfire occurrence is moderated by a range of factors including land management practises, land-use change and ignition sources.