What follows is a petition/action alert from the California Chaparral Institute. – mk

STOP destruction of 20 million acres of habitat and protect our communities from fire

The California state government has just refused to do what is necessary to protect us from the wind-driven wildfires that kill the most people and destroy the most homes.

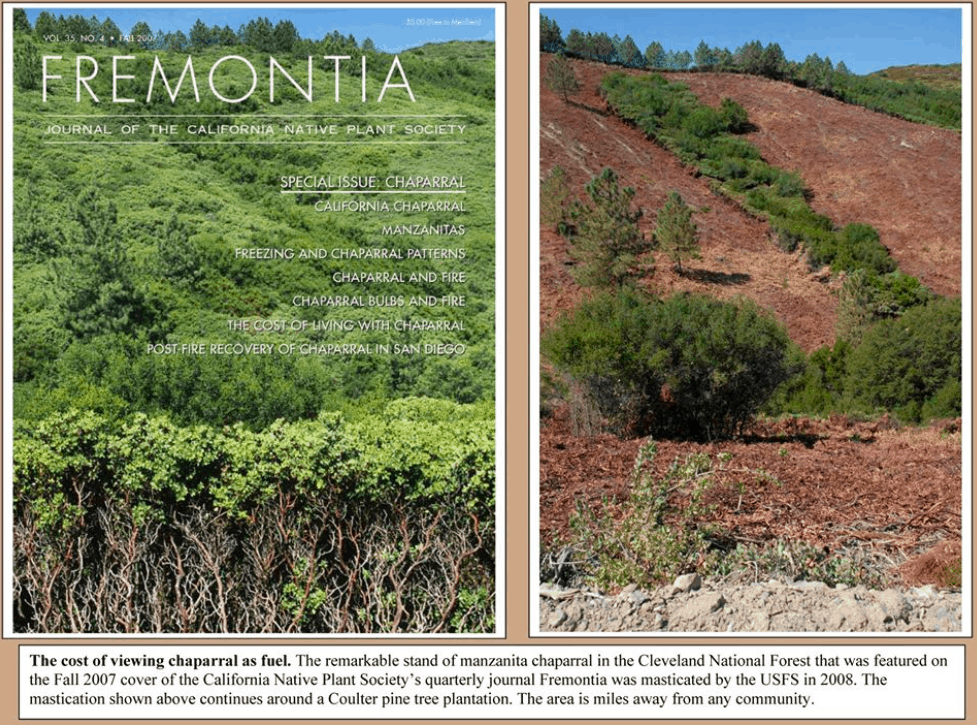

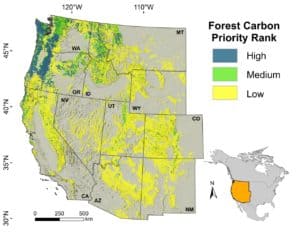

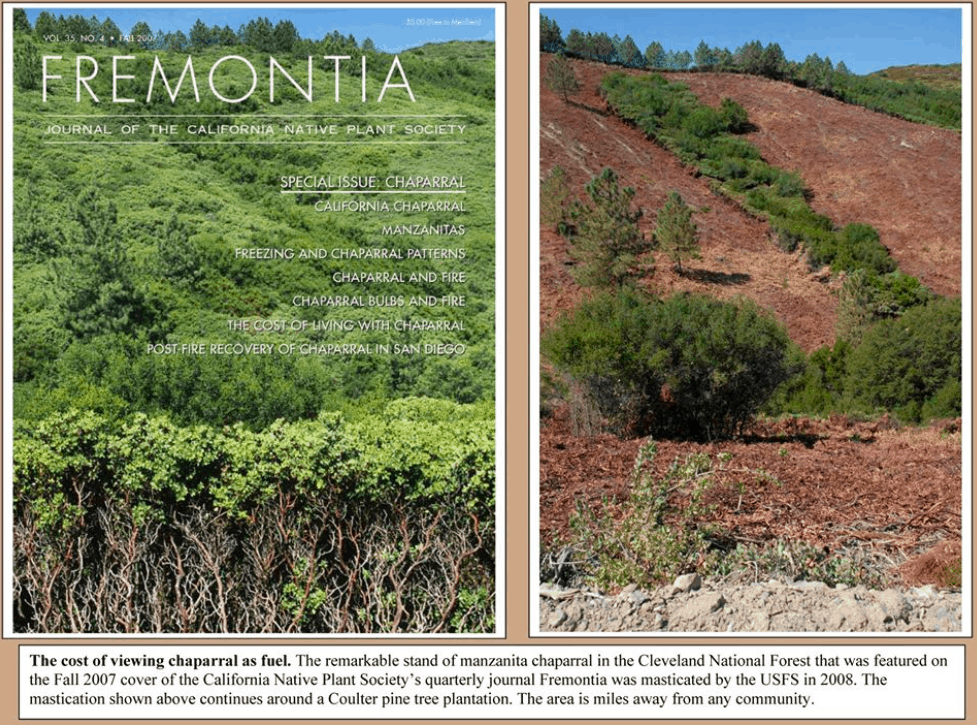

Their solution? To double down on what they’ve always done – clear 250,000 acres of native habitat per year (20 million acres total targeted) through grinding, burning, and herbicides in their proposed Vegetation Treatment Program (VTP).* Even though the state admits that this approach will fail to protect lives and property during the most devastating wildfires, it nonetheless remains California’s priority solution to the wildfire problem.

Here is what the state admitted in response to our proposals to make communities fire safe:

“When high-wind conditions drive a large fire, such as when large embers travel long distances in advance of the fire, vegetation treatment would do little, if anything, to stop downwind advance of the fire front.”

In other words, the state is going to ignore the fires that cause the greatest loss of life and property. Instead, Cal Fire, the state fire agency, will only address 95% of the fires – the ones they can easily control under calm conditions.

This is absurd. Imagine if we designed buildings to withstand only 95th percentile earthquake movements, or what you would feel as a result of a magnitude 2.5.

The science is clear. Proper vegetation management around homes and directly around communities is an important part of reducing fire risk. But the wholesale destruction of the natural environment is not.

We need to follow the science. We need to protect communities from the fires that actually do the most damage. And we need to stop pretending we can control Nature by destroying hundreds of thousands of acres of native habitat through Cal Fire’s proposed Vegetation Treatment Program (VTP).

The California state government has shown a pattern of failure when it comes to protecting us.

State politicians say they agree that making communities fire safe is a priority, but Governor Newsom rejected $1 billion in funding to do so. Instead, he championed a $21 billion program to protect utility corporations from liability for the fires they cause. The state promotes it’s efforts to protect biodiversity, yet it is planning on clearing 250,000 acres/year of native habitat under the guise of fire protection.

The California state government needs to fulfill the main obligation it has to its citizens – protect them from harm.

What you can do:

Please sign this petition and forward it to family and friends.

Dear Governor Newsom,

We urge you to reject the California Board of Forestry’s and Cal Fire’s current approach to dealing with wildfire – clearing habitat as described in their recent final Environmental Impact Report (PEIR) for the Vegetation Treatment Program (VTP).

1. Reject Cal Fire’s refusal to protect us from the growing threat of extreme, wind-driven wildfires. Cal Fire’s approach wastes millions of tax-payer dollars and fails to protect communities most at risk.

2. Immediately develop and fund a comprehensive and effective program to reduce the flammability of our communities through retrofits, exterior sprinklers, etc., so that our communities can survive wind-driven firestorms. We can do it, but it will require objective leadership OUTSIDE the Cal Fire bureaucracy, a bureaucracy trapped by its own paradigm paralysis – they can’t think outside their own priorities. Assemblyman Wood’s bill (AB 38), passed last term, provided an opportunity to make communities fire safe, but you did not support funding the program. The funding needs to be reinstated.

3. Develop and promote the policies needed to:

a. form community fire safety teams that will develop evacuation plans for actual disasters that will occur (not the minor events that we have been able to control in the past),

b. create fire safety parks WITHIN threatened communities where people can go and remain safe during a wildfire

c. form community-based volunteer fire response teams of people who DO NOT evacuate, but stay to assist their disabled and/or trapped neighbors

d. STOP the *unsustainable practice* of placing people in harm’s way by allowing development in known fire corridors

Here is a complete list of recommendations.

ADDITIONAL DETAILS supporting this petition

*To see the VTP, you can go to this link:

https://bofdata.fire.ca.gov/projects-and-programs/calvtp/

In case you might think the title of our petition is hyperbole, here is the text from the VTP EIR:

“Expansion of CAL FIRE’s vegetation treatment activities to reach a total treatment acreage target of approximately 250,000 acres per year to contribute to the achievement of the 500,000 annual acres of treatment on non-federal lands…” Page ES-2

And…

“Using this method, 20.3 million acres within the 31 million-acre SRA were identified that may be appropriate for vegetation treatments as part of the CalVTP…”

Page ES-3

An added note:

87% of the destruction to communities in 2017-18 was caused by 6 wildfires (out of 16,000), all wind-driven. The VTP admits it doesn’t address those. Let that sink in for a bit.

Here is the Los Angeles Times’ editorial that repeats much of what we are saying in this petition:

Editorial: California will never control raging wildfires if it doesn’t stop building in high-risk areas

By The Times Editorial Board

Nov. 29, 2019

After three years of devastating and deadly wildfires, perhaps we should no longer be surprised by them.

It was shocking in 2017 when the Tubbs fire jumped the 101 Freeway and charred a suburban subdivision in Santa Rosa. It was unthinkable last year when Paradise residents had to run for their lives as the city was almost entirely destroyed by the Camp fire. And still people were caught off guard last month when the Saddleridge fire forced hundreds of residents in Sylmar and Porter Ranch to flee their homes in the middle of the night.

A terrifying pattern has been revealed. California’s wildfires are now regularly destroying subdivisions and established neighborhoods that once seemed at low risk from wildfires. There’s ample scientific data and research to explain why: Climate change amplifies natural variations in the weather, leading to more frequent and more destructive wildfires. Poorly maintained utility lines are setting blazes.

Despite that, we’re still building homes — more and more of them — in fire-prone areas. State and local leaders have been slow to adopt the housing, land-use and development reforms that would make California communities much safer in the coming years. Here are a few suggestions culled from experts that, if enacted soon, could deliver lasting security.

Harden homes

The devastation in Paradise, Santa Rosa, Ventura County and Malibu demonstrated that homes are not only casualties in the fires, but also the fuel that feeds and exacerbates the blazes. Wind-driven fires can blow embers over great distances. The embers lodge under eaves, get sucked into vents or broken windows and can ignite a house from the inside out, which creates more embers and more heat. The fire then spreads from house to house, sometimes leaving surrounding trees largely untouched. The first and most obvious step is to retrofit homes in high-risk areas to make them more resistant to fire. Researchers analyzed some 40,000 buildings exposed to wildfires between 2013 and 2018. They found that homes built to keep out embers and withstand extreme heat were much more likely to survive. Yet so far, the state has done little to require home hardening or to fund it.

The needed retrofits aren’t very expensive. Homeowners should cover their vents with fine wire mesh and enclose their eaves to prevent embers from getting inside the structure. Double-paned windows are less likely to shatter in high heat, and steel shutters can help too.

Properties also need regular inspections to make sure they are prepared for fire season. Are there gaps in roof tiles that might allow embers into the attic? Are the gutters full of dry leaves and twigs? Do the residents know to shut the doggie door when they evacuate?

Earlier this year, Assemblyman Jim Wood (D-Healdsburg) proposed creating a billion-dollar revolving loan fund to help homeowners pay for retrofits and to remove flammable vegetation near their homes. The funding was cut from the bill.

Next year, Gov. Gavin Newsom and state lawmakers should invest that $1 billion — or more — to help people in high-risk areas make their homes more fire resistant. But it’s not enough to have individual homeowners voluntarily harden their houses if neighboring properties are tinder boxes. Fire is contagious. The greatest protection comes when entire neighborhoods are hardened together and maintained together. Whatever legislation is passed should reflect that.

Buy out burned properties

Still, all the fire-resistant materials and hardening in the world can’t guarantee safety. During the 2017 Thomas fire in Ventura County, new houses built to the strictest fire codes still burned down. The houses were in a state-designated “very high fire hazard severity zone,” which means the area has the greatest probability of burning based on vegetation, topography and fire history. And when 80-mile-per-hour winds blow embers across a landscape that is already prone to burn, the fire can quickly overwhelm hardened homes.

State officials have to recognize that there are some homes and neighborhoods that shouldn’t be rebuilt. Or rebuilt again, since some communities have burned more than once. For decades, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has helped buy out properties destroyed by flood waters, in a bid to stop the expensive and sometimes deadly cycle of flood-rescue-and-rebuild in high-risk areas. In Texas, communities have used a combination of local bonds, drainage fees and federal dollars to buy out flood-prone houses.

Buyouts are considered one of the most cost-effective ways to prevent flood destruction. These are voluntary sales and the government pays fair market value. The homes are demolished and the property becomes open space. It’s pricey to buy up dozens of properties at a time, but it can be cheaper and more effective than developing new flood control infrastructure.

Yet there’s been little discussion in California of trying to use FEMA grants or other funds to make similar buyout offers in high fire-risk areas. It wouldn’t be possible to buy out every property owner in the very high fire hazard severity zones — there are an estimated 2.7 million Californians living there. Rather, a buyout program could target the areas at the very greatest risk, perhaps because the community was built without adequate evacuation routes, or because the neighborhood has been burned two or more times before.

Don’t build in high fire-risk areas. But if development must be approved, build exceptionally safe communities

The best way to prevent wildfire destruction and death is to stop building houses in the path of fire. Half of all buildings destroyed by wildfire in California over the last 30 years have been in developed areas next to wildlands.

So far, though, gentle suggestions that local governments should consider wildfire risk when approving development aren’t working, and neither is Newsom’s call to “deprioritize” development in high fire-risk areas. Land-use decisions are made by local elected officials and they’ve proven themselves unwilling to say no to dangerous sprawl development and equally unwilling to say yes to denser, urban infill housing construction that would be more sustainable. Just look at Los Angeles County, where the Board of Supervisors approved construction of a 19,000-home mini-city to be built at Tejon Ranch in a remote valley that has been deemed a high risk for wildfires.

California lawmakers need to push — even force — local elected officials to make more responsible development decisions.

Earlier this year, Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson (D-Santa Barbara) introduced Senate Bill 182, which would prohibit cities and counties from approving new housing developments in high fire-risk areas unless the projects meet new “wildfire risk reduction standards.” Those would include siting the homes so they have natural fire breaks and are easier for firefighters to defend, building evacuation routes, and having an ongoing, funded program to inspect and maintain defensible space around homes.

The bill was held up amid concerns that it could allow anti-growth cities to use the presence of some high fire-risk areas within their borders as an excuse to shirk their responsibility to build enough housing in the non-fire-risk areas of the city. That should not be allowed.

Yes, California has a severe housing shortage that is making the state unaffordable and unlivable for too many people. But the state can’t keep counting on sprawl to solve the housing crisis. That only puts more people at risk in future wildfires, and it generates more greenhouse gases as residents commute from far-flung subdivisions. That hastens climate change, which, in turn, worsens wildfire conditions in California.

The entire history of the state’s effort to ignore the fires that cause all the damage can be found here:

http://www.californiachaparral.org/threatstochaparral/helpcalfireeir.html