Here’s a press released from Western Watersheds Project:

Saint George, UTAH – Western Watersheds Project is suing the U.S. Forest Service in Utah for allowing ongoing overgrazing on Monroe Mountain by a handful of non-compliant permittees. The agency, faced with threats of armed resistance, has capitulated to rancher demands allowing excessive stocking rates, repeated trespass, and non-compliance with federal regulations.

“When the Forest Service tried to do the right thing and suspend these livestock grazing permits for multiple willful violations of the terms and conditions, the ranchers responded with threats of violence,” said John Persell, staff attorney with Western Watersheds Project. “That’s an ugly ultimatum, and it’s unfortunate that the Forest Service has to deal with these folks. But it’s unfair to the Americans who own these public lands to let them be continually degraded by scofflaws.”

The Forest Service has gone overboard in accommodating these bad actor permittees, working around the requirements for permit renewals by repeatedly offering “temporary” permits to the ranchers, unlawfully failing to respond to appeals of grazing decisions, ignoring requirements to incorporate sage-grouse protections into permits, and allowing increases in cattle numbers the agency never environmentally analyzed.

“When I visited these allotments last month with other members, we saw severe over-use of new aspen shoots and native bunchgrasses, as well as damage to riparian areas near springs,” said Laura Welp, an ecosystems specialist for Western Watersheds Project. “We could visibly see the degradation of these lands due to years of hands-off management by the Forest Service.”

In the spring of 2019, the agency’s Washington office intervened to order local Forest Service managers to waive basic permit terms requiring ear-tagging of cattle on public lands, and to allow the Monroe Mountain permittees onto the allotments despite ranchers’ attempts to re-write permit terms and conditions eliminating any land stewardship obligations.

“Allowing Cliven Bundy to get away with trespass grazing for over twenty years has surely sent a message to other fringe property rights ranchers that threats of violence work with federal agencies,” said John Persell. “However, the Forest Service is beholden to its own regulations and all of us as public land owners. This lawsuit will affirm the rule of law.”

A copy of the complaint can be found online here.

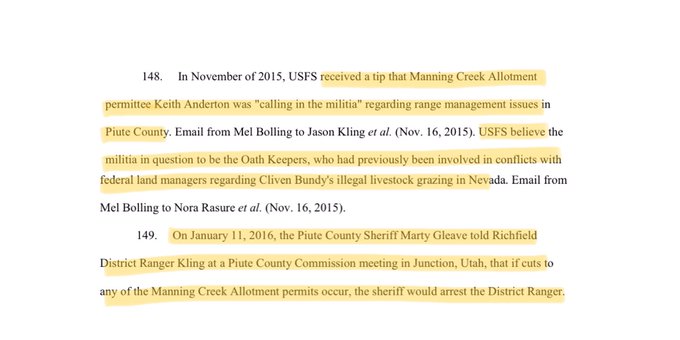

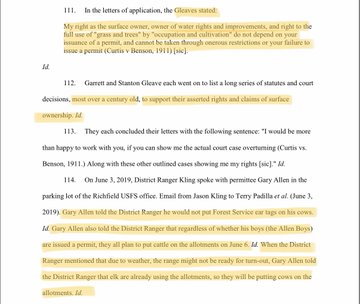

Here are some excerpts from the lawsuit: