I’d like to thank Susan Jane Brown, Anonymous, and others for engaging deeply and thoughtfully on the proposed NEPA regs. They’ve brought up many good points, which I’m going to try to separate into different threads. This one is about scoping. I’m hoping we can all get on the same page about what is required by the current scoping, and what practices are actually used.

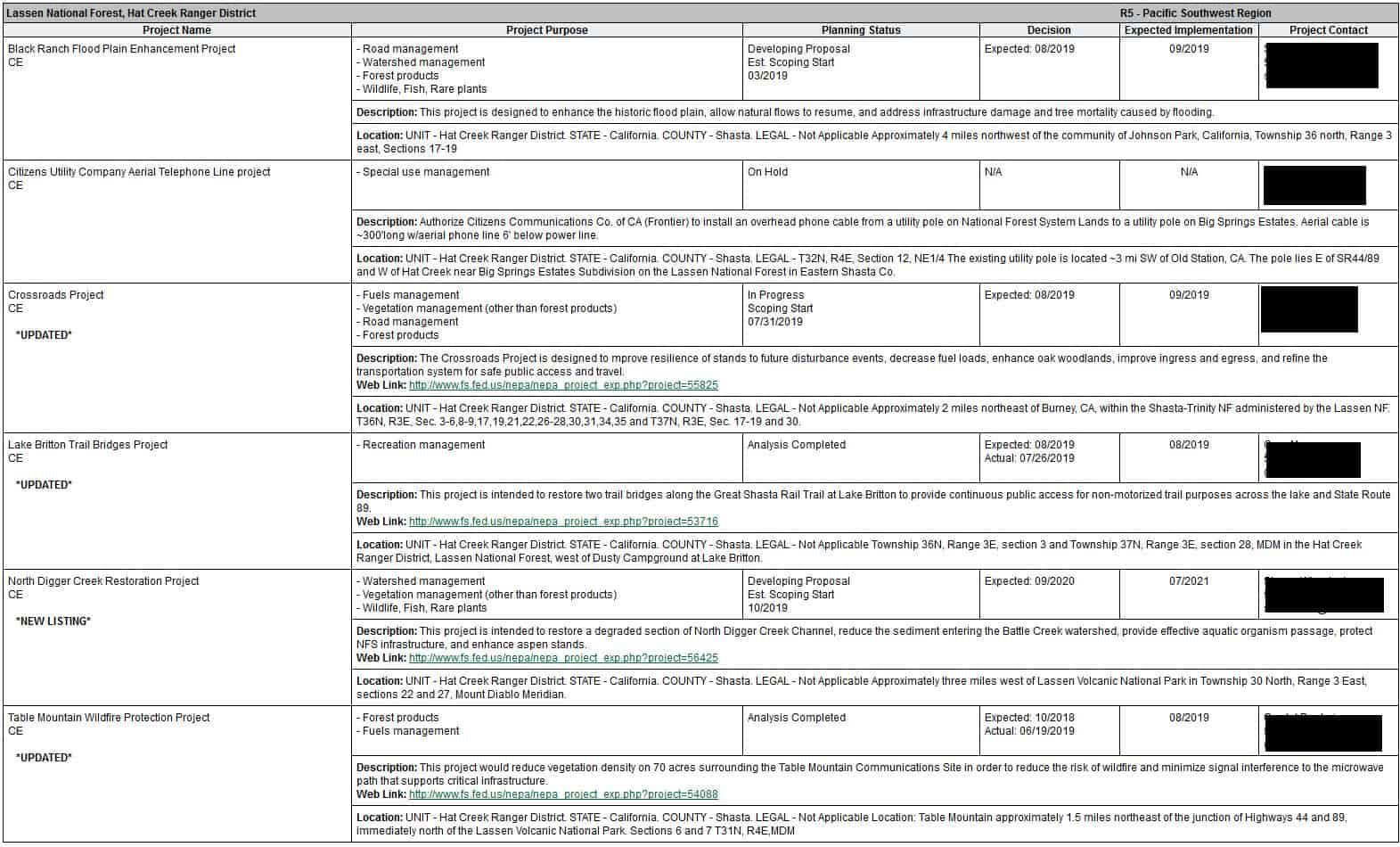

One of the main talking points against the proposed reg is reducing public involvement. So we can look into exactly what happens now, and how that might change. I found this helpful information in the Forest Service (2012) NEPA Handbook. Note: my understanding of why the Forest Service developed their own NEPA regs in 2008 was so that they would have more legal oomph. The Forest Service’s sister agency in multiple use, the BLM, does not have NEPA regs but operates from a Handbook.

Here’s what the Handbook says about scoping:

Although the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) regulations require scoping only for environmental impact statement (EIS) preparation, the Forest Service has broadened the concept to apply to all proposed actions. Scoping is required for all Forest Service proposed actions, including those that would appear to be categorically excluded from further analysis and documentation in an EA or an EIS (§220.6). (36 CFR 220.4(e)(1))

A reasonable argument could be made that (all) other agencies scope without it being a requirement. Agencies like the BLM, for example. So the idea that the Forest Service would never scope without the requirement seems, to me, to be unlikely. Why did the Forest Service decide to do this when no other agencies do? Maybe someone out there knows that history and would share their knowledge.

So what does the scoping requirement require exactly? Here’s what the Handbook says:

The process of scoping is an integral part of environmental analysis. Scoping includes refining the proposed action, determining the responsible official and lead and cooperating agencies, identifying preliminary issues, and identifying interested and affected persons. Effective scoping depends on all of the above as well as presenting a coherent proposal. The results of scoping are used to clarify public involvement methods, refine issues, select an interdisciplinary team, establish analysis criteria, and explore possible alternatives and their probable environmental effects.

The methods and degree of the scoping effort undertaken for a given project vary depending on scope and complexity of the project (see the CEQ scoping guidance).

Scoping shall be carried out in accordance with the requirements of 40 CFR 1501.7. Because the nature and complexity of a proposed action determine the scope and intensity of analysis, no single scoping technique is required or prescribed. (36 CFR 220.4(e)(2))Selection of scoping techniques should consider appropriate methods to reach interested and affected parties. For example, a project with potential localized effects to a small community might consider posting fliers at locations where they are likely to be seen.

This is all very interesting, as when CEQ talks about scoping, they are not thinking about the Forest Service, but are thinking about EIS’s, so it is the first step of a very long and complicated process with lots of requirements (doing an EIS).

At the same time, there don’t seem to be any specific requirements in the Handbook, other than “no single scoping technique is required or prescribed.” If it is “use your common sense” then what difference does it make to have the requirement? Note: I could argue this either way, if there’s a requirement to “use your common sense” versus just “using your common sense.”

(1) I could argue that having the requirement is suitably innocuous, so why get rid of it? How many court cases have there been about scoping? (I have no idea). The other point of view would be “why have an extra requirement that no other agency has?”. I couldn’t tell what the rationale was from the discussion on page 27545 of the proposed Rule, so we can only assume that it was to simplify the requirements. While this has been portrayed by some as being about “more logging” there are many CE’s that are much less likely to cause concern (and some, like the oil and gas one that we seldom hear about in op-eds) that might cause more concern.

(2) Given that, one could have another alternative in which scoping could be kept for some subset of CE’s, especially the new restoration CE (26) since the 3000 acre legislative CE’s require collaboration.

(3) It seems to me that there are solutions that could actually be better than just scoping. It seems like the idea of putting a project on the SOPA, with a name to submit comments to is seen to be not enough, but I think it may be just right for something like “shoulder widening or other safety improvements within the right-of-way for an NFS road.” But maybe the whole SOPA could be made more user-friendly. For example, people might fill out a form so that they could be notified of all projects and an email sent to them. And it might be handy for regional or national groups for this to be made so that they could sign up for all the relevant forests. We discussed these kinds of things about 15 years or so ago when the E-gov initiative was going on and the PALS database developed. It makes sense to me that notification and commenting could be streamlined and that responsibility for giving input could be shared somehow between the agency and interested parties.