I ran across this NPR story about possibly moving USDA Agencies NIFA and ERS out of the Washington D.C. area. I think it’s altogether possible to critique initiatives without hyperbole e.g. “hostility toward science” but the more intense the expression, the more likely to be quoted, I guess.

I ran across this NPR story about possibly moving USDA Agencies NIFA and ERS out of the Washington D.C. area. I think it’s altogether possible to critique initiatives without hyperbole e.g. “hostility toward science” but the more intense the expression, the more likely to be quoted, I guess.

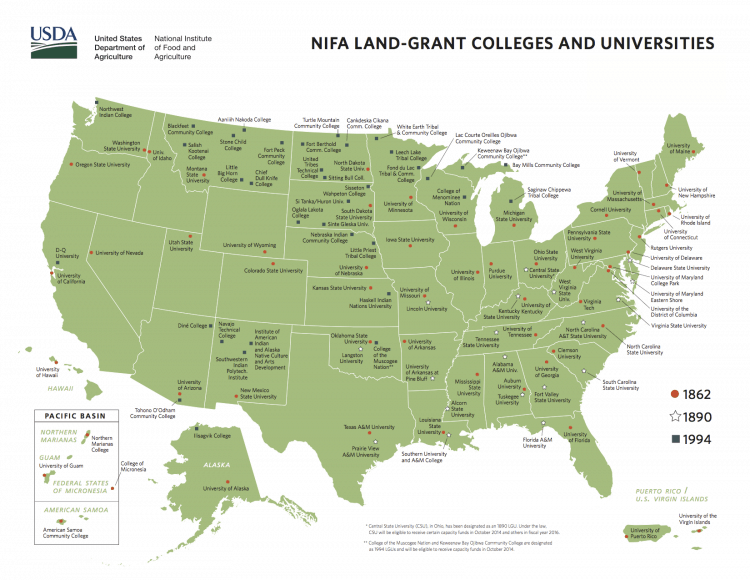

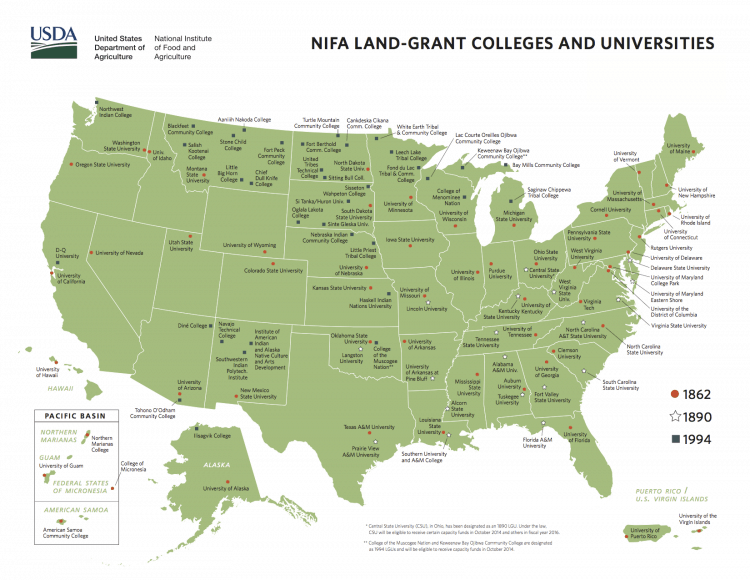

Many Forest Service folks may not be familiar with NIFA and their forest research programs. This seems like a good time to highlight their work. See this link.

It’s interesting that this article fits the story into the idea box (I guess it’s maybe a “trope” ) of “the war on science.” Since I am a former employee of NIFA (when it was known as CSREES) I’d like to give two arguments for why the move might be “good for science.” I’ll stick to NIFA and leave it to your own consideration whether my arguments might apply to ERS.

I don’t know how many of you have tried to hire people for positions in DC. It’s not always easy. I’ve tried to hire scientists for the FS and for NIFA, and also NEPA folks in the Forest Service.

First, you can get better employees and they may well be happier in their location. If we use the idea recently discussed about fire folks, that “people should lead what they know”, then we would want folks from the land grants to work at NIFA. Now consider the kinds of towns that have 1860, 1890, and 1994 land grant universities and other affiliated institutions (check out the map above). The cost of living is lower. They are not crowded (or not relatively compared to DC). The public schools tend to be better. I spent 14 lovely years in D.C., but most people from a land grant university town may well not want to move their families there. Why did I get a job with NIFA? I wanted a promotion and had the qualifications. I was not the “best candidate” by any means, but I was already in DC , so found myself in a pretty shallow applicant pool.

But many in the research community said efficiency isn’t driving the move. It’s hostility toward science.

“I think that moving the agencies out of D.C. is going to significantly dilute their effectiveness as well as their relevance,” says Ricardo Salvador, who is the Director of the Food and Environment Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

The plan is to leave some folks in DC according to these stories. In terms of NIFA, when I worked there, my office was in a rented building near the L’Enfant Plaza Metro. Honestly, I could have been anywhere. I traveled to review university programs, but I never visited the Congress nor I don’t think anyone in the “head shed” as we called the USDA building (until I was called on the carpet, but that’s another story). We were absolutely outward looking to where the work was and the communities we served (research, education and extension), so it’s a peculiar argument that folks with jobs like I had “need” to be in DC to be “effective” and “relevant.”

Second, part of who you are is who you hang with at work, and who you talk to, which papers you read or what people are discussing on your Nextdoor app, and so on. With people at the agency in DC and also elsewhere, you’d get more diverse perspectives within your workforce. It seems to me that you can argue it either way.. one way is that locality doesn’t make any difference because we all consume the same media and are all interconnected via teaming apps, (so why not move to somewhere cheaper? ) or locality does matter, and so you should be near the people you serve or study.

Now if I were Secretary, I would not move people against their will because it is so disruptive (remember the move to Albuquerque Service Center?) and you might lose precisely those employees you want to keep. I would let those who want to go, go, and let the others be virtual employees- and hire all the new folks at the new site. I bet if the FS had to do the ASQ thing over, they would do it this way.

Here’s a piece on the top three sites.

If we get away from the “war on science” partisan mantra, we can see that there are many arguments why this might be a good idea, and many ways to mitigate negative effects. And IMHO it’s most peculiar that the idea that moving to the Midwest will give us poorer science goes unquestioned at, of all places, Minnesota Public Radio.

I ran across

I ran across