Here’s the press release from the Southern Environmental Law Center. A copy of the study is available here.

ATLANTA – A study, conducted by researchers at the University of Georgia’s (UGA) Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, found strong support for the preservation and expansion of wilderness areas among public land visitors living within a half-day drive of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. The new report reveals 89 percent of respondents across the Southeast support the preservation of wilderness areas and 88 percent of those who had visited a wilderness area thought more wildlands should be protected.

“It’s clear from these findings that there’s nothing more valuable in a crowded world than wild, untamed places,” said Sam Evans, Leader of the Southern Environmental Law Center’s National Forests and Parks Program. “While these places belong to all of us as Americans, when you’re in wilderness, the experience is yours alone.”

The Appalachians are an iconic American mountain range with more than half of the U.S. population living within an 8-hour drive of its southern region. The wildlands located here offer one of the East’s greatest opportunities for escape, exploration, adventure and have been instrumental in shaping the region’s rich history for centuries. Despite this, researchers studying human to outdoor interactions have known little about how Southerners perceive, use, or view these protected areas.

“This research was conducted as an effort to better understand the use and demand for Southern Appalachian wilderness,” said Kyle Woosnam, UGA Associate Professor of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management. “While wilderness areas are important for their ecological, social and economic contributions, little is known about how residents use and perceive these public lands. The intent of this study was to do just that.”

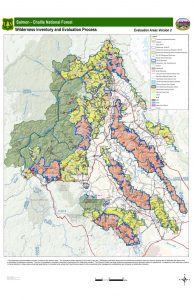

This Southern Appalachian region is also home to nearly 50 wilderness areas that span almost half a million acres, stretching from Alabama to Virginia. Researchers surveyed 1,250 residents in Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee who had visited a protected natural area (ex: wilderness, state park, national scenic area, etc.) in the last five years, with questions focusing most closely on residents’ perceptions of and experiences in the Southern Appalachians. The research was funded by a grant from the Southern Environmental Law Center and The Wilderness Society.

Highlights from the study include:

• People most often visit wilderness areas for day hiking, photography, swimming and camping

• Positive perceptions of wilderness spanned across the political spectrum

• Word of mouth was the #1 way people found out about wilderness areas

• Participants expressed a high level of emotional attachment to wilderness areas visited

• The protection of water quality and wildlife habitat were the most important wilderness benefits identified

• The natural qualities of wilderness were considered the most valuable characteristics of these areas

The results of the study come just after Congress’s December 2018 approval of a wilderness designation for 20,000 acres of the Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee. That designation expanded the existing Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock, Big Frog, Little Frog Mountain, Big Laurel Branch and Sampson Mountain Wilderness areas and created the Upper Bald River Wilderness Area, a new 9,000-acre addition to the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Unlike most federally managed forests, which allow for extractive uses like timber production or built facilities for human comfort and convenience, wilderness areas have only a single guiding purpose—to remain in a natural state. Under the Wilderness Act of 1964, areas that receive wilderness designation by Congress are forever protected as wild places, preserving these areas for future generations, protecting wildlife, rare species habitat, and water quality, acting as a buffer against the damaging effects of climate change, providing economic benefits to rural communities and unparalleled recreation opportunities for all that visit.

“These unique public lands allow us to experience and create memories in some of the country’s wildest places,” said Jill Gottesman, The Wilderness Society’s Southern Appalachian Conservation Specialist. “These areas are some of the most valuable, intact lands in the continental U.S. due to their connectivity, biodiversity and sheer remoteness. This study shows that Southerners are ready to work together to protect our Southern Appalachian wildlands for future generations.”