Bob Zybach and I went on a field trip to the Rim Fire. The first stop on the tour showed us the Sierra Pacific Industries’ salvage logging results. I’m posting a medium resolution panorama so, if you click on the picture, you can view it in its full size. You can see the planted surviving giant sequoias on their land which were left in place. You can also see some smaller diameter trees, bundled up on the hill, which turned out to be not mechantable as sawlogs. You might also notice the subsoiler ripping, meant to break up the hydrophobic layer. They appear to have done their homework on this practice, and it is surprising to see them spending money to do this. SPI says that their salvage logging is nearly complete, and that they will replant most of their 20,000 acre chunk next spring. They have to order and grow more stock to finish in 2016.

Throwback Thursday Hits NCFP!

After the “Siege of 1987”, and 43 wildfires on the Hat Creek Ranger District, in three days, the Lost Fire burned up this forest up on the Hat Creek Rim. Even without terrain effects, this fire raged through the forest incinerating everything in its path. There is an eerie beauty in this picture, reminiscent of an Ansel Adams monochrome image.

Today, those forests are growing back, after a big reforestation program, and it appears, a subsequent thinning. Here is a Google Maps view of that area today.

https://www.google.com/maps/@40.8027893,-121.4002792,862m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en

Already this summer, there has been 3 large wildfires on this Ranger District. It is mostly a dry “eastside pine” forest, requiring trees to be thinned and crowns separated. It appears that the Forest Service is finally seeing that early thinning is key to restoring forests. In the past, it always appeared that they were “gambling” on waiting for the trees to get bigger (and more profitable), before managing their plantations.

In Idaho, Tracing What Remains After the Flames

Dick Boyd sent me this article featuring the Sawtooth National Recreation Area. The Stanley area is one of my favorite spots, with hot springs, jagged peaks, pristine lakes, spacious meadows and abundant wildlife.

As we neared Stanley, Idaho, a hamlet carved by creeks and framed by mountains with spiky peaks that reminded me of a punk rocker’s hair, the landscape surrounding the winding highway on which we’d climbed 7,000 feet gave way from rugged canyon to flat expanse of grass speckled by lodgepole pine and aspen. We were on the northern edges of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, three hours from Boise, when scars from an old fire came into view.

My daughter, Flora, and I had been playing a makeshift game in which we pointed out the nature surrounding us, the sort of mindless thing you do to entertain a 5-year-old on a road trip. I see a deer, I see a birdie, I see snow, I see a purple flower, we called out.

“I see trees,” I said, pointing to a cluster of an unrecognizable species to our left, their crooked branches denuded by flames that had torched them.

“Those are not trees,” Flora retorted. “Trees have leaves!”

This article reminded me of the time I spent working on the Boise National Forest, after the massive 1994 Rabbit Creek Fire took 2 months to burn before the Sawtooths and fall rains finally extinguished it. The public rarely sees any of the 150,000 burned acres, as it isn’t visible from the highways. I stumbled upon this vintage video that shows how devastating such fires can be, as storms deposit moderate rains upon highly hydrophobic soils.

It is not always easy to display the damages that occur when soils cannot absorb even moderate rainfall. As the storms and high winds came in, that day, Forest Service employees were called in, due to the danger. Oddly enough, they forgot about me. I weathered the storm, not knowing what was happening. The next day, I patrolled the roads, finding a plugged culvert, with excessive soil movement. I pulled out my trusty shovel and diverted all the water into the roadside ditch, getting it to flow down and through the next downhill culvert.

What causes old forests to burn?

Gil is right that we’ve had this discussion, and we agreed to disagree. He reaffirmed his belief that acres burned is the result of lower logging levels:

“Your wisdom is so infinitely better than mine, so I must be seeing things when I look at a graph that shows acres burned by year. Naturally, someone who doesn’t understand the scientific principles behind forest ecosystems would say that it is just coincidence that acres burned by year shows a very significant up turn since the 80% reduction in harvest levels.”

Here is the basis for a different belief. This comparison of acres burned to the Pacific Decadal Oscillation cycle is taken from the Assessment for the revision of the Nez Perce-Clearwater Forest Plan in Idaho. It led the planning team (who presumably understand scientific principles) to conclude:

“When PDO data are overlaid on the fire statistics an interesting correlation is seen. A period between 1940 until 1980 was in the cool wet phase, which would have limited wildfires while at the same time promoted tree growth, regeneration, and significant increases in forest density. Clearly cool wet trends resulted in lower wildfire occurrence regardless of the fuel loading across the region. Climate is the most controlling factor for wildfire and the one we can least influence.” (my emphasis)

Every scientist knows that correlation is not causation, and there are at least two opinions possible based on these facts. I was, and am still, asking for some more definitive research results that would justify Gil’s confidence that more logging is the answer.

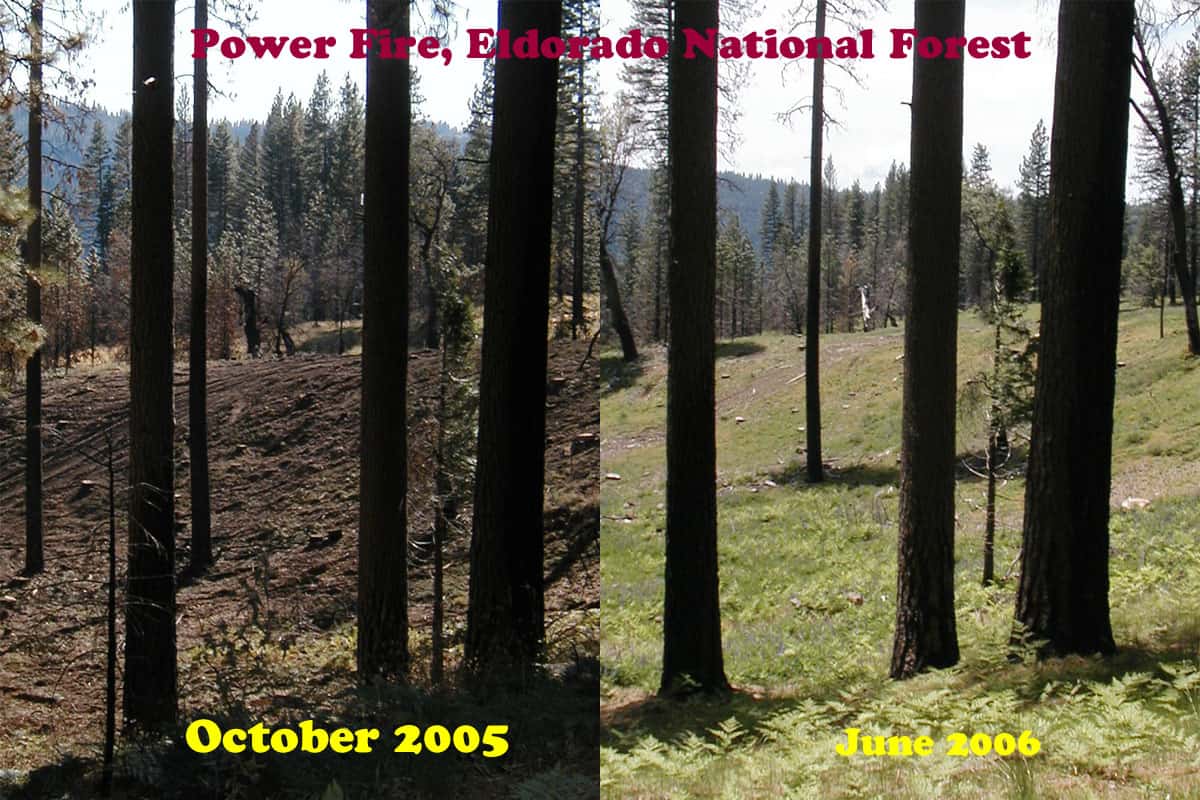

Repeat Photography: Part Deux

It’s kind of a challenge to assemble pictures shot in different years, from different spots, and from different cameras. This is an excellent way to view and monitor trends, showing the public what happens over time to our National Forests. Sometimes, you have to look hard to see the differences. In any future repeat photography projects, I will be using very high resolution, to be able to zoom in really far.

One of the reasons why you don’t see much “recovery” is that the Eldorado National Forest has finally completed their EIS for using herbicides in selected spots, almost 10 years since the fire burned. This is part of the East Bay’s water supply. Sierra Pacific replanted their ground in less than 2 years. So, the blackbacked woodpeckers should be long gone, as their preferred habitat only lasts for an average of 6 years. As these snags fall over, the risk of intense soil damages from re-burn rises dramatically. Somewhere, I have some earlier pictures of this area which may, or may not line up well with this angle. I’ll keep searching through my files to find more views to practice with.

Summer Blogging Break

It was 40 years ago this summer, that I started UC Berkeley Forestry Summer Camp in Meadow Valley, California. That program took us from various other colleges and universities and brought us together as a class for the next two years. Summer camp was my initiation to the path, career and vocation of forestry.

I thought you all might get a hoot out of these photos of us hippies in Camp ’74. You can click on the photo to enlarge and check the names in case you recognize someone.. Here’s the link if you want to find another class or more people from my class.

If you know any of the folks in the photo, please ask if they’d be interested in submitting a post reflecting on their last 40 years to this blog..

And here is a link to an entertaining camp song with Al Stangenberger. And, guess what, Cal Forestry is 100 years old this year- here’s a link to more info and about the festivities!

A happy and safe rest of the summer to all!

Sound Forest Management?

We hear the term ‘sound forest mangement’ (I’ll use ‘SFM’) a lot around here. I’m not quite sure what it means, though I suspect that others feel confident that they do. I do believe it can mean quite different things to different people, leading to radically different viewpoints on how to get there. And since “getting there” is presumably one reason to even think about a “new century of forest planning” (as opposed to simply recycling the last century), I thought I’d toss this out to get kicked around.

By the way, the accompanying photos from the web are just a semi-random assortment of forestry related scenes, good/bad/ugly/otherwise, and aren’t posted for the purpose of editorializing.

Old school: This represents the bulk of what I studied in forestry school, back in the late 70’s, probably some of you did too: Silviculture, Forest Mensuration, Forest Economics, Wood Technology, Forest Management… etc. I do think the “agronomy of trees” is very well developed and documented. There may be no truly sustainable yield (of timber), but we know how to come pretty darn close. Being able to grow trees indefinitely, with a predictable periodic or continuous yield, with minimal exogenous inputs (fertilizer, herbicides etc.), at some level of profitability, pretty much constitutes what I learned was SFM. Renewable resource, etc. It contrasts with the extreme and unsustainable approaches of “cut out and get out”, and what we used to call “lawnmower forestry” with its often high input requirements.

Wildlife: I didn’t learn much about wildlife in forestry school, though we were departments in the same college, and courses were available to those who had extra electives to fill. Most of my exposure to wildlife was hearing a little in dendrology class how some trees/shrubs (serviceberry, for example) were useless for forest products but were “good for wildlife”. I don’t remember ever hearing about nesting, denning, cover, corridors, etc. Basically, wildlife was a foreign language that I didn’t feel I needed to learn.

I’ve been learning more about wildlife lately, although somewhat unevenly emphasizing ESA-listed species, FS sensitive species, and management indicator species. Wildlife (including fish) issues are hugely important in national forest management issues, controversies, and litigation. The values, goals, benchmarks, and philosophy tend to be quite different from those needed to optimally grow merchantable trees. That’s another way of saying that wildlife and tree people tend to define SFM very differently. As a result, every plan and decision tends to involve a very large measure of compromise.

Soils and microbiology: I had terrible, trivial courses in those subjects as a forestry undergraduate. Those two profs have since left this world, so I don’t feel bad about saying that. Now that I teach courses in soil microbiology and plant pathology, I try hard to get forestry students in my classes and relate the importance of those subjects as best I can to forestry (and ag of course). Mostly I get grad students though, because forestry undergrads have their schedules pretty booked up already.

New School: I’m not sure there is one, probably some universities are doing better now than mine did. Forest Ecology seems to be a popular catchphrase, but it probably downplays the actual growing of trees, which is important, and there are only so many hours in the curriculum. The USFS approach hinges on “muldisciplinarity”, with teams of specialists contributing, but it’s unclear how much those disciplines communicate, or how much the decision-making ranks understand about how all the pieces fit together. Here’s one definition of multidisciplinary research: “Researchers from a variety of disciplines work together at some point during a project, but have separate questions, separate conclusions, and disseminate in different journals.” Kind of the Tower of Babel approach, and hasn’t been all that effective in my opinion.

Another approach, so-called “transdisciplinary research”, seems more promising: Specialists contribute their unique expertise but strive to understand the complexities of the whole project, rather than one part of it. Transdisciplinary research allows investigators to transcend their own disciplines to inform one another’s work, capture complexity, and create new intellectual spaces.

I have a little trouble envisioning the transdisciplinary approach ever permeating the USFS, given its very hierarchical, turf-protective, and quasi-military structure, but one can always hope. It’s a pipe dream, but maybe NCFP can one day serve as a role model…

Conflict Resolution Mechanisms: Public vs. Private Oil and Gas

While we’ve been having this discussion about settlements, I’ve been thinking a couple of things and following the newspaper on oil and gas in Colorado.

Let’s say there is way “a” of looking at things. NGOs have policy objectives. Litigating on NEPA, NFMA and ESA is a way of meeting those objectives. NEPA is convenient because you can find holes if you are smart and careful enough. This can delay people or make them give up, or negotiate with you, or if you wait long enough the material can lose its value, or the price of say, coal, can be too low and the project will not happen. NEPA claims seem to be used as a tool to delay or stop projects or make plans more in line with the plaintiff’s views.

Way “b” is articulated by others on this blog better than I, but is along the lines of “the FS does not follow the “rules” and NGO’s make them enforce the rules (related to the environment). Environmental impacts are said to depend on the intensity of impact, the frequency and the area impacted, so I am curious why some NGO’s choose the projects they do to worry about enforcing the rules. For example, hazard tree projects are a yawn in Colorado and a Big Deal in Montana. It doesn’t seem to me to do with the environmental impacts being all that different, nor the quality of the NEPA documents. So there must be a different explanation.

I thought some comparisons with oil and gas in Colorado might be helpful. Here there is some on the federal estate as well as private. There is no doubt about the value of the jobs and the funds given to communities and states.

First, here is a settlement discussed for the Roan Plateau. Now if the BLM has been working on this for all these years (since way before I retired) it seems like they could have done any NEPA that a judge required. Seems more like “A” to me; see my italics as to those “in the room.” Here’s a link to the story.

A proposed settlement that could free up some oil and gas leases within the Roan Plateau study area for drilling and do away with others should not come at the expense of future mineral lease payments to local governments, Gov. John Hickenlooper has pledged.

“The Hickenlooper administration believes a settlement that allows some energy development to proceed while protecting other areas of the Roan Plateau is in the interest of all parties,” Henry Sobanet, director of Hickenlooper’s Office of State Planning and Budgeting, wrote to state Rep. Bob Rankin.

Rankin, R-Carbondale, has been working with the governor’s office on a deal to prevent future federal mineral lease dollars from being withheld from local entities in order to refund about $28 million to Bill Barrett Corp.

The proposed settlement involving Barrett, environmental groups and the federal government has been touted as a potential “win-win” by those involved.

The exception has been local governments, including Garfield County, which have asked that they be held harmless in the deal.

Of particular concern is the state’s practice of withholding future federal mineral lease dollars, including royalties from producing wells, that normally would be distributed to local governments to help pay for impacts from energy development, instead of asking those entities to refund money that already has been paid out.

The deal could end several years of litigation over natural gas drilling on the Roan Plateau northwest of Rifle, where the U.S. Bureau of Land Management has reopened the federal environmental impact review that led to leases being issued in 2008.

Under the proposed settlement, Barrett would be reimbursed some of its federal leases in the more pristine areas atop the Roan Plateau.

In exchange, Barrett and other lease holders would be allowed to develop less-controversial leases, including in areas that already have active gas wells.

There is also an issue of oil and gas development and regulations for towns and communities. Recently it looked like Governor Hickenlooper tried unsuccessfully to broker a solution. But what was on the table was litigation and legislation. Now, this is under the state’s jurisdiction, hence the legislation alternative. Here’s the link to one story:

At the statehouse news Monday conference, Hickenlooper and Polis outlined the compromise, which involves four steps.

The governor create the commission to make recommendations to the legislature — by a two-thirds vote.

Hickenlooper had tried for months to broker a legislative compromise, but that effort collapsed in July.

“This may be the template for what happens in the rest of the country,” Hickenlooper said, noting similar conflicts are roiling in Texas, Wyoming and Pennsylvania. “This is the way we do things in Colorado. We work through our differences and difficulties. Maybe no one is perfectly happy, but it serves all parties.”

Polis said it was “better to address these issue in rule or by legislation, but if that doesn’t work, you’ve got to go to the ballot box.”

Private land.. many people including diverse representatives of the public need to agree. Public land.. NGO’s Barrett, and the feds need to agree.

Repeat Photography and Salvage Logging Recovery

My first attempt at assembling pictures, showing how quickly salvage impacts can “heal”. Here is the current aerial view of this specific area.

https://www.google.com/maps/@38.4831284,-120.3639833,223m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en

Here is a view of a re-burn that has already occurred, in the same area. Notice the lack of significant mortality, due to having salvaged the area, reducing the fuels of the inevitable future fires.

https://www.google.com/maps/@38.4770266,-120.3464336,892m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en

One of the biggest “purpose and needs” in the Sierra Nevada is fuels reduction after a wildfire. Otherwise, re-burns, like the Rim Fire will dominate the landscapes for an indefinite amount of decades.

Seven out of 10 of the world’s largest glaciers in Bridger Wilderness?

This is a bit off topic, but…. I happened to notice this caption to a beautiful photo on the USFS’s Managing the Land page (www.fs.fed.us/managing-land):

Bridger Wilderness extends 80 miles along the Continental Divide with seven out of 10 of the world’s largest glaciers. The landscape is breathtaking with hundreds of alpine lakes, glacial cirques and wide sweeping valleys. (U.S. Forest Service)

Can that be true? I’d guess that there are many larger glaciers in Antarctica, Greenland, Iceland, Alaska, etc.