Folks, an acquaintance has asked for help in finding information about the 6 Federal Sustained Yield Units established under the Sustained Yield Forest Management Act of 1944. I know a little about the Lakeview unit, the only one that still exists, I think, but nothing of the others. What happened to the others — Vallectios, Flagstaff, Grays Harbor, Big Valley, Shelton? Anyone know of a paper or article that looks at these as a group?

Examining Historical and Current Mixed-Severity Fire Regimes in Ponderosa Pine and Mixed-Conifer Forests of Western North America

The other day I got the following note and link to some new relevant research from Douglas Bevington, author of The Rebirth of Environmentalism: Grassroots Activism and the New Conservation Movement, 1989-2004. Bevington’s note is shared below with his permission, along with a link to the new study and article. . – mk

——————

I wanted to let you know about an important new study that was just published by the high-profile science journal PLOS ONE. The article, titled “Examining Historical and Current Mixed-Severity Fire Regimes in Ponderosa Pine and Mixed-Conifer Forests of Western North America,” was co-authored by 11 scientists from various regions of the western US and Canada.

Their study found that there is extensive evidence from multiple data sources that big, intense forest fires were a natural part of ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer ecosystems prior to modern fire suppression. These findings refute the claims frequently made by logging and biomass advocates that modern mixed-severity forest fires (erroneously called “catastrophic” fires) are an unnatural aberration that should be prevented through more logging (“thinning”) and that more biomass facilities should be built to take the resulting material from the forest.

In contrast to these claims, logging done ostensibly to reduce fire severity now appears to be not only unnecessary, but also potentially detrimental when it is based on erroneous notions about historic forest conditions and fire regimes. These findings have big implications for biomass and forest policy, so I encourage you to take a look at this article.

The full article in PLOS ONE is available here.

Here are a few key points from the abstract and conclusion:

Abstract, p. 1

“There is widespread concern that fire exclusion has led to an unprecedented threat of uncharacteristically severe fires in ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests of western North America. These extensive montane forests are considered to be adapted to a low/moderate-severity fire regime that maintained stands of relatively old trees. However, there is increasing recognition from landscape-scale assessments that, prior to any significant effects of fire exclusion, fires and forest structure were more variable in these forests….We compiled landscape-scale evidence of historical fire severity patterns in the ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests from published literature sources and stand ages available from the Forest Inventory and Analysis program in the USA. The consensus from this evidence is that the traditional reference conditions of low-severity fire regimes are inaccurate for most forests of western North America….Our findings suggest that ecological management goals that incorporate successional diversity created by fire may support characteristic biodiversity, whereas current attempts to ‘‘restore’’ forests to open, low-severity fire conditions may not align with historical reference conditions in most ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests of western North America.”

Conclusion: p. 12

“Our findings suggest a need to recognize mixed-severity fire regimes as the predominant fire regime for most of the ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests of western North America….For management, perhaps the most profound implication of this study is that the need for forest ‘‘restoration’’ designed to reduce variation in fire behavior may be much less extensive than implied by many current forest management plans or promoted by recent legislation. Incorporating mixed-severity fire into management goals, and adapting human communities to fire by focusing fire risk reduction activities adjacent to homes, may help maintain characteristic biodiversity, expand opportunities to manage fire for ecological benefits, reduce management costs, and protect human communities.”

Forest Restoration: Problems & Opportunities in Words & Pictures

Western forestlands have never been in worse shape: millions of acres of dead and rotting trees; thousands of miles of abandoned and barely maintained roads; record wildfires becoming larger, deadlier, and more destructive by the year; hundreds of artificially impoverished rural communities; and endless litigation preventing the use of resources we need to sustain our lives and our economy.

There are a number of reasonable ways to resolve these problems; a long-term commitment to active forest restoration and management seems to offer the most immediate benefits to both people and wildlife, and is the likely route to economic sustainability as well.

What is forest restoration, why is it needed, and how is it done are the questions addressed in this article. Two examples of current forest restoration projects are profiled to help answer these questions, and illustrate how these types of programs can be immediately implemented across the landscape to the benefit of neglected forests and depressed timber-producing communities throughout the West.

What is Forest Restoration?

The process of forest restoration is focused on returning an area to one reflecting desired past conditions, it is critical to understand a) what conditions were actually like in the past, and b) which of those characteristics (if any) should be restored or preserved for the future.

For the past 10,000 years and longer, Native Oregonians have used plants and animals for their own purposes: principally for food; shelter; fuel; and fiber products, such as clothing, basketry, musical instruments, canoes, ropes, and weapons. Fire was used for a wide range of purposes: for cooking, heating, and lighting areas around homes and campgrounds; for rejuvenating berry patches and harvesting fields of grain; for hunting game by systematically setting vast tracts of land on fire.

Man is the only animal that can use fire, but he is not the only animal that benefits from it. The expert and judicious use of fire across the ancient landscapes of Oregon resulted in the stable patterns of forests, woodlands, vast prairies, wetland meadows, brakes, balds and berry patches encountered by Oregon Trail immigrants in the 1840s and 1850s. Elk, deer, songbirds, fish, squirrels, migratory fowl, and other animals that populated these environments were documented by many of the new residents.

Forest restoration, means restoring people to the land, whether in the woods, along a river, or walking through a town. Restoring people to the land also supposes restoring fire to the land; fires set by people, not lightning.

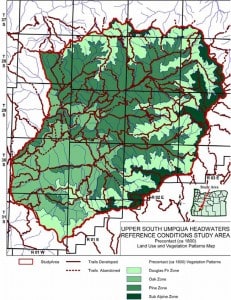

Upper South Umpqua Project: Considering Past Conditions is Step 1.

The maps shown in this article represent a critical step in the forest restoration process – a determination and documentation of likely past conditions for areas being considered for restoration. Whenever we plan to restore something, it is important we understand the conditions that existed in the past.

The “Upper South Umpqua Headwaters Precontact Reference Conditions Study” focused on characterizing a significant portion of the Umpqua National Forest in Douglas County, as it likely existed in 1825. The study area is slightly more than 230,000-acres in size and extends from the crest of the Cascade Range westward to the confluence of Jackson Creek with the South Umpqua River. The map shows the location and composition of forest type patterns as they likely existed in the study area 200 years ago. Each of the subsequent four photographs documents a typical example of each of the four forest types, and illustrates potential forest management actions needed to restore and maintain desired future conditions.

One of the basic purposes of forest restoration is to reduce wildfire risk and damages. The method for achieving this in overstocked stands of conifers is to significantly reduce their biomass (“fuel load”) and open up the tree canopies (“thinning”) as they existed in earlier times, when catastrophic-scale crown fires were uncommon occurrences. On federal lands this is referred to as an “FRCC 1” condition.

The Upper South Umpqua Project was initiated by Douglas County Commissioner, Joe Laurance, to consider the possibility of restoring degraded local forestlands to presettlement condition. On July 15, 2010, he testified to a Congressional subcommittee of The House Natural Resources Committee in Washington, DC:

“Fire Regime Condition Class (FRCC) 1 is similar to the forest which European explorers first found here. That forest had been modified by fire for more than six thousand years to provide the native inhabitants with what were then life’s necessities. These included abundant wild game from the most productive and diverse wildlife habitat ever known on this continent. Similarly, the regular burning of competing vegetation permitted propagation of nut bearing trees and other food producing plants. Additionally, the historic “Healthy Forest” promoted pristine rivers, streams, and lakes that provided an abundant harvest of fish and waterfowl. Within FRCC 1 the risk of losing key ecosystem components to fire is low, while vegetation species composition, structure, and pattern are intact and functioning within the natural historic range.”

Research methods used to determine and document 1825-era forest conditions in the study area included extensive use of General Land Office survey maps and notes, historical maps and photographs, field plots, oral history interviews, literature reviews, archival research, and over 5,000 GPS-referenced digital photographs. This latter method documented the location and extent of remaining old-growth (pre-1825) trees in the study area, in addition to documenting persistent patterns and patches of such traditional cultural food and fiber plants as camas, fawn lilies, cat’s ears, huckleberries, hazelnuts, chinquapin, tarweed, serviceberry, wokas, bracken fern, thimbleberries, and salal.

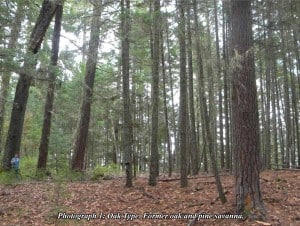

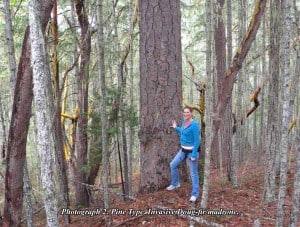

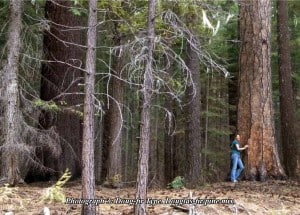

Historical research has given us the map shown: a generalized depiction of likely forest conditions in the study area during the 1800-1825 time period. The following four photographs represent current typical conditions within each of the four forest types (or “zones”) shown on Map 4. The large size and wide spacing of the older trees in the photographs can be gauged by the “human scale” used to measure them: Nana Lapham, long-time forest science research assistant of NW Maps Co., did much of the field work on this project.

Photograph 1 shows relict trees from an oak and pine savanna that was developed and used by native residents for hundreds or thousands of years. These areas were tended by constant gathering of fuel, acorns, and pine nuts from the trees and regularly tilling and/or burning the surface area to manage understory crops, such as camas, tarweed, hazel, and beargrass. Notice how Douglas-fir have invaded the area in the past 100+ years, threatening the survival of the few remaining old-growth oak and pine.

Photograph 2 is a typical condition found throughout the former Pine Type in the study area. Again, these areas were maintained by regular prescribed fires in precontact time, and continuous canopy of fine, pitchy fuels. A crown fire under these circumstances would likely kill all of the trees in this picture, including the old-growth.

Restoring this savanna would entail removing the Douglas-fir, before they smother the remaining old-growth, removing the surface fuels that have built up around the bases of the oaks and pines, and reintroducing the understory plants and regular burning practices that created and maintained savanna conditions in the first place. There are thousands of acres similar to this throughout the study area, with invasive Douglas-fir slowly killing the established old-growth and creating potential crown-fire conditions by developing a are now being threatened by thousands of invasive Douglas-firs and madrone.

Photograph 3: Doug-fir Type. Douglas-fir/pine mix.

Photograph 3: Doug-fir Type. Douglas-fir/pine mix.

Photograph 3 shows the 1825 Douglas-fir Type, which still contains scattered old-growth sugar and ponderosa pine; species which may have dominated this type in the Indian era. Restoration provides the best option for prolonging the lives of these historic trees, too.

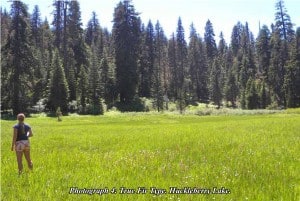

Photograph 4: True Fir Type. Huckleberry Lake.

Photograph 4: True Fir Type. Huckleberry Lake.

Photograph 4 is a picture of Huckleberry Lake, in the high elevation True Fir Type. The “lake” is now a wetland prairie. This area used to be a portion of a major huckleberry gathering complex, equally accessible to Indian families living in the Rogue River and South Umpqua basins before these plants were shaded out by the invading conifers. The taller trees in the background represent larger diameter, older trees likely dating to the 1600s and 1700s; the vast majority of trees, though, having established themselves after the mid-1800s and throughout the 1900s.

The common theme throughout these maps and photographs is that tens of thousands of acres of old-growth oak, pine, Douglas-fir, red cedar, and other conifers exist throughout the study area are in need of immediate attention, if they are to survive. The same problem exists for the scattered patches of huckleberry, camas, tarweed, and native grasses that still persist. A forest is, ideally, composed of many facets, housing many different types and species of plants and animals. Those are the types of attributes that used to define these lands, and the same types that can be restored and maintained for future generations of people and wildlife.

Jims Creek Project: Make a Choice and Then Do It is Step 2.

The second step to forest restoration, is to determine what future conditions are desired and to begin actively restoring and/or maintaining those desired conditions across the land. An excellent example of this step is the Jims Creek forest restoration project on the Middle Fork Willamette Ranger District, which is in the process of completing an initial 400-acre “demonstration project” portion of a 25,000-acre plan.

The Jims Creek project has demonstrated the feasibility, profitability, and general benefits of conducting landscape-scale forest restoration projects on federal forestlands, but it is also a good example of how much time can be spent in putting these projects together, as well as the ease and quickness with which they can be stopped by adversarial legal actions. This project was initially conceived by a local US Forest Service forester/project manager, Tim Bailey, who then spent the better portion of the next ten years shepherding his vision through the myriad public meetings, scientific reviews, committee presentations, promotional tours, and other hurdles needed to get things underway on the ground.

Picture 5 shows Bailey in front of a portion of the Jims Creek Project in 2010. This area had already been treated by removing most of the invasive conifers established during the past century, and by broadcast burning the ground so as to remove excess litter and logging debris. Note the scattered trees that have been left behind: widely spaced pine of several different age groups, from seedlings to saplings and second-growth to old-growth. Also note the small herd of elk grazing directly above Tim, near the crest of the hill.

Picture 6 is the same herd of elk as the previous picture, seen through a zoom lens. The small charred stumps and large woody debris in the foreground will soon rot away or be consumed in the next few surface fires. The reddish-brown pattern is bracken fern, a plant harvested in large quantities by many Oregon tribes for its starchy roots and asparagus-like “fiddleheads” that grow in the spring. In a few more years, with a few more broadcast burns, this area will appear very similar to what it must have looked like hundreds of years ago.

Additional restoration has been halted at this time due to an infestation of red tree voles (“tree mice”) that accompanied the migration of Douglas-fir trees into the project area during the past century. These rodents are protected against logging under a federal “survey and manage” regulation, despite the fact they are not a threatened or endangered species.

This type of work stoppage, based on new federal regulations and litigation initiated by environmental organizations, has become the main difficulty in beginning and completing forest restoration projects in Oregon and throughout the West. Of the 25,000 total acres of this project within the Middle Fork Ranger District, 7,000 acres are privately owned and managed for maximum timber production; more than 7,000 acres have been classified as spotted owl habitat; approximately 7,000 acres are in remote areas that would likely include the “taking” of spotted owls; and the remaining 4,000 acres are populated with regulated tree voles. A river flows through the project area that contains two listed fish species and “there is a perception on the part of the regulatory agencies that this type of restoration work can have a negative effect on fish.”

Despite these hurdles, there is a lot of work needing to be done and a lot of people wanting to do it.

Conclusions

Forest restoration projects should be conducted on a landscape-scale basis in order to be effective biologically, aesthetically, and economically. Project boundaries should include sufficient commercial materials to treat the project area and show a profit. Profitable and beneficial actions are sustainable on a long-term basis, as we have learned from more than 10,000 years of forest history in this region.

The actions needed to restore our forests to earlier, more desirable conditions would create thousands of jobs for decades, jobs to make the best use of our resources, protect our old-growth and its wildlife, and greatly reduce the likelihood and severity of wildfire when they did take place. Based on my own experiences and observations, I think there are four things that must be in place for forest restoration projects to be successful on a long-term basis:

1) Areas slated for restoration should include sufficiently broad boundaries and specifications to allow projects to be profitable;

2) Restoration projects should be landscape-scale (25,000 to 250,000 acres) in size in order to be economically efficient and biologically effective over time;

3) Local residents and businesses should be in strong support of restoration projects, and be given access to all information that develops during the process;

4) Local project managers should be knowledgeable and capable of communicating scientific, technical, and political aspects of a project to local citizens.

I remain certain that the adoption of these practices, as defined, would have many immediate and positive effects on forest health, old-growth preservation, endangered species protection, rural economies, international trade balances, and many other economical, ecological, cultural, historical, aesthetic and recreational values associated with Oregon’s forests.

The degradation, destruction, and loss of our federal forests and grasslands to wildfire, bugs, and disease will continue to escalate so long as we continue our current path of passive avoidance and neglect. Restoring our Nation’s forests means restoring people – in part, as active managers – to our lands. The benefits for doing so have been listed; the impediments to getting started have been largely self-inflicted, are almost entirely political (rather than scientific or humanitarian), and can be readily surmounted, given effective leadership or common outcry. The best time for doing something is now.

Tribal Forestry and The Anchor Forest concept – Is it Appropriate for our National Forests?

This is from the Bellingham Herald

Some pertinent quotes include:

– “They call this concept Anchor Forest because this is tribal land — these people are not going anywhere. They’ll be here forever,”

– ““The goal is not to cut trees based on what sawmills need,” McGee said. “We need sawmills aligned with products that come off the projects that are doing good ecological restoration.”

The Yakamas own the only remaining sawmill in the region. It employs about 200 people, Rigdon said, and supports more jobs in the tribe’s forestry program.

A key part of the Anchor Forest plan, Rigdon said, is a study to determine how much wood should be coming off the region’s forests so the tribe and others can develop a market for those timber products and plan investments in new sawmill equipment or to build a pellet plant, for example.”

– “Karen Bicchieri, who manages the Tapash, says everyone involved wants the same thing — resilient forests.”

– ““In working together to improve the health of the ecosystem, we’ve got to be balanced and do it in a way that is beneficial from a social standpoint to build and sustain communities,” Blazer said. “When you bring (the tribes’) traditional knowledge with Western science, you can really develop strong forest management. There’s lots to learn from each other.””

To me this is what our National Forests should be all about.

An Oregonian’s Plan for Federal Forests: Untying the Gordian Knot

I have been a friend and business associate of Wayne Giesy’s for more than 25 years. During that entire time he has discussed with me – and anyone else who will listen – his ideas for resolving the conflicts surrounding the management of our nation’s forests; and particularly those forests in the western US.

During the past 30 years conflicts between the timber industry and environmental activists regarding the management of our federal lands have become so well known they are commonly referred to as the “Forest Wars”: a conflict in which opponents have taken sides in regards as to whether our federal forests should be actively managed principally for economic benefit of local and national interests, or whether they should be allowed to “function naturally” for intrinsic values and not necessarily be subjected to harvesting at all. These conflicts are not peculiar to just the western US, but have also been taking place in other countries, too, such as Brazil, Venezuela, Australia, and Tasmania.

Wayne’s proposed solution, commonly known as the “Giesy Plan” for many years because of its principal authorship, is to divide the lands into two parts: one to be managed for multiple use – with an economic focus — along more traditional lines, and the other to be managed in accordance with environmental concerns. The former approach would be subject to existing state and federal laws and regulations regarding riparian areas, road construction, etc., and the latter would allow for whatever harvests were needed to maintain forest health, recreational uses, wildlife habitat, and other environmental concerns. These separate approaches would be taken for an 80-year period to fully test them out, and then reconsidered at that time based on existing results and perceptions.

This “Oregon Plan” has been discussed in many venues and with many individuals – industrial foresters, tree farmers, politicians, and environmentalists — over the past 30 years (Wayne is now in his mid-90’s), and modified accordingly as it was being considered. Most recently Wayne met with Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber in a one-to-one meeting and was encouraged by the Governor’s thinking on the federal forest management issue. They discussed how changing the current management paradigm in ways that better achieve balance across all interests might obtain support not just within Oregon, but also as applied across all federal forestlands nationwide.

Is this the solution to resolving past conflicts and moving forward with the management of common resources? A growing number of people and organizations on both sides of the table seem to think so.

http://www.orww.org/Awards/2013/SAF/Wayne_Giesy/Oregon_Plan/index.html

The Oregon Plan

Nick Napier, Dave Rainey, Wayne Giesy, and Bill Hagenstein at the Portland Wholesale Lumber Association’s 2010 annual meeting in Portland, Oregon. Wayne has promoted his idea for improved management of Oregon’s federal lands to forest industry, environmental organizations, and elected officials for the past 30 years, during which time it has become known as “the Giesy Plan.”

Sometime in 1983, after Wayne Giesy first began work as an employee of Ralph Hull, of Hull-Oakes Lumber Co. in Dawson, Oregon, Wayne approached Ralph with his concerns on increasing environmental actions to restrict logging activities on federal lands. At that time Wayne thought, in order to secure a stable supply of logs from BLM O&C Lands — where Hull-Oakes then obtained most of its raw materials — a deal should be made between the forest industry and the environmental organizations to divide the disputed lands into two portions: 1/2 for environmental purposes and 1/2 for public product needs (see: Giesy 2008a). After nearly a year considering this idea, Ralph gave Wayne the authorization and encouragement needed to present this idea to other forest industry leaders, with full backing of Hull-Oakes Lumber Co.

When Wayne first presented his idea to a number of forest industry leaders he was openly laughed at, and accused of “giving away the farm” by other members of these groups who couldn’t conceive of the environmental organizations having enough power or credibility to obtain such a major commitment of public resources. At that time local loggers and sawmill owners had access to perhaps 85% of the standing federal timber in Oregon; today that number is much closer to 15%, as the remainder has been dedicated to “critical habitat” for Threatened and Endangered Species, riparian “reserves,” Wilderness, roadless areas, and other designated “set asides.”

Wayne’s idea first became publicly known through an editorial written and published by long-time and well-respected Albany Democrat-Herald editor, Haso Herring, in May 2003. Although Herring’s editorial focused more on Wayne’s suggestions on how to deal with salvage from recent western Oregon Wildfires rather than a basic division of all federal lands, he used the name “Giesy Plan” to label Wayne’s thoughts: “The Giesy plan sounds visionary because it is based on common sense and assumes that obstacles can be overcome. That’s the way most Americans used to think. Would that more of us did so now.”

Today the name “Giesy Plan” is used more often to represent his original proposal, as it had been used for some time prior to the Herring editorial. Although its influence is generally not recognized or acknowledged in ongoing debates regarding the same problems that existed 30 years ago, current proposals strongly mirror Wayne’s original proposed suggestions and certainly have their basis in his unvarying advocacy. During the past two years, for example, there has been significant political discussion concerning the need to resolve the long-standing debate between forest industry and environmental groups in regards to the O&C Lands in western Oregon. Every one of these efforts has focused on a division of public forestlands between competing timber production, environmental preserves, and riparian reserves — as first suggested by Wayne in the early 1980’s, and as actively advocated by him ever since. Current examples follow:

In 2012 Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber formed an O&C Lands task force to address the problem of those forests to meet their federally mandated obligations. On February 6, 2013 the task force released a 96-page report that offered a series of options — each based upon Giesy’s principal suggestion that the lands be divided between the opposing factions and managed according to their individual perspectives. A series of graphs on page 46 of the report illustrated each of the proposed options, each one being based on Giesy’s basic argument to divide the land between resource production and forest preservation:

Also in 2012, Oregon Congressmen Peter DeFazio, Greg Walden, and Kurt Schrader developed a proposal, integrating the Kitzhaber report and based on the same concept developed by Giesy regarding the division of federal forestlands. The resulting proposed legislation, called the DeFazio-Schrader-Walden O&C Bill, was included by fellow Congressman Doc Hasting as part of the successful House Bill 1526. It has been generally supported by western Oregon members of the forest industry, but opposed by numerous environmental organizations, such as Oregon Wild, a long-time activist group based in Eugene, Oregon.

Simultaneous to Governor Kitzhaber’s efforts and those of Oregon’s bipartisan Congressional team, Oregon Senator Ron Wyden — initially working with fellow Oregon Senator Jeff Merkley — has been fashioning a separate solution to the western Oregon O&C Lands stalemate, generally referred to as “the Wyden Bill.” Senator Wyden’s efforts began in 2011 and are based on a “legislative framework” he developed that features as its basis: “The legislation will create wilderness and other permanent land use designations whose primary management focus will be to maintain and enhance conservation attributes. This acreage will be roughly equivalent to lands designated for sustainable harvest”; i.e., the same approximate 50/50 split first suggested by Giesy moere than 30 years ago, and actively promoted to the Senator, his staff, and many others ever since. Wyden’s proposal was publicly released on November 26, 2013, and was immediately opposed by most environmental organizations, such as Oregon Wild, and by the major western Oregon timber industries in a co-sponsored press release. On the following day the American Forest Resouce Council — which generally favored the DeFazio Bill — released a more critical response through their monthly AFRC Newsletter.

A more detailed look at the Giesy Plan — and the need for corrective management of federal lands in Oregon and in the remaining western States — illustrates the basic dependency of the Kitzhaber O&C Report, House Bill 1526, and the Wyden proposal on Wayne’s original concerns and recommendations:

Page 1. Proposes a division of US Forest Service lands in the 11 western states as: 40% for environmental concerns; 10% for riparian protection; and 50% “to produce products for the American public,” with certain conditions and restrictions. Ten “benefits” of adopting this idea are also listed, including: rural jobs, elimination of county payments, reduced imports, improved international balance of payments, reduced wildfire risk, enhanced wildlife habitat, and an elimination of existing “negative activities” by both sides of the debate.

Page 2. Offers modifications to the original proposal, following consultations with both environmental and timber management proponents, with management divisions being made along watershed boundaries.

Page 3. A 2010 report using Oregon Department of Employment figures, showing 72,000 jobs lost in Oregon from 1989-2008 due to reduced forest management levels; and compared to 88,000 Oregon government jobs created during the same time period.

Page 4. A graphic comparison of the relative amounts of federal land contained in each of the eleven western states as compared to federal land holdings in the 37 eastern states (Hawaii and Alaska are not shown).

Page 5. Two graphs depicting the increasing trends of both total wildfire acres burned annually in the US, and for average size of each wildfire during the 1960-2006 time period: with sharp increases in both trends beginning in the early 1990s.

Page 6. A bar graph comparing Net Growth of US Forest Lands compared to Product Removals for the same lands during the 1952-2004 time period: 52 years in which forest growth has always exceeded harvests, and in which the greatest disparities between the two correlate strongly with the increased wildfire trends shown on Page 5.

Cal Fire Under Fire: Ordered to Pay $30 Million to Landowner

This article was published in Today’s Sacramento Bee regarding Superior Court Judge Leslie Nichols’ order for Cal Fire and the State of California to pay $30 million to Sierra Pacific Industries for damages related to the 2007 Moonlight Fire. I’ve posted the first several paragraphs; the link to the complete article follows.

Judge orders Cal Fire to pay $30 million for ‘reprehensible conduct’ in Moonlight fire caseBy Denny Walsh and Sam Stanton [email protected] Published: Wednesday, Feb. 5, 2014 – 9:41 pm In a blistering ruling against Cal Fire, a judge in Plumas County has found the agency guilty of “egregious and reprehensible conduct” in its response to the 2007 Moonlight fire and ordered it to pay more than $30 million in penalties, legal fees and costs to Sierra Pacific Industries and others accused in a Cal Fire lawsuit of causing the fire. The ruling is the latest twist in an epic legal battle that began not long after the fire erupted on Labor Day 2007, scorching more than 65,000 acres in Plumas and Lassen counties. Sierra Pacific, the largest private landowner in California, was blamed by state and federal officials for the blaze, with a key report finding it was started by a spark from the blade of a bulldozer belonging to a company working under contract for Sierra Pacific. But company officials have steadfastly denied responsibility and have accused the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and the U.S. Forest Service of conspiring to cover up their own shortcomings that allowed the fire to rage out of control. Even after Sierra Pacific agreed to settle a federal lawsuit over the devastation in two national forests by paying $55 million in cash and handing over 22,500 acres of land to the government, the company insisted it was undone by an erroneous ruling of U.S. District Judge Kimberly J. Mueller, and then was a victim of stonewalling by Cal Fire in that agency’s Plumas County suit, including the alleged withholding of thousands of pages of key internal documents relevant to the legal struggle. In a 28-page order issued Tuesday, retired Superior Court Judge Leslie C. Nichols essentially agreed with all of Sierra Pacific’s points, adopting a separate, 57-page order proposed by Sierra Pacific and the other defendants almost word-for-word, and excoriating the behavior of Cal Fire and two lawyers from the office of Attorney General Kamala Harris, which represented the agency. “The court finds that Cal Fire’s actions initiating, maintaining and prosecuting this action, to the present time, is corrupt and tainted,” the judge wrote. “Cal Fire failed to comply with discovery obligations, and its repeated failure was willful.” The agency withheld documents for months, “destroyed evidence critical (to the case) … and engaged in a systematic campaign of misdirection with the purpose of recovering money from (Sierra Pacific).” (Click link below for remainder of the article.) Call The Bee’s Denny Walsh, (916) 321-1189. Read more here: http://www.sacbee.com/2014/02/05/6132239/judge-orders-calfire-to-pay-30.html#storylink=cpy |

Risk vs. Reward

Since I didn’t get any takers with my PS to Anatomy of a Timber Sale Appeal post (not even any snark!), maybe these statistics will stir some conversation.

The fatality rate for U.S. automobile driving is 0.128 fatalities/million hours driven (net of pedestrians killed by autos).

The fatality rate (10-year average) for USFS-related firefighting aircraft is 44.2 fatalities/million hours flown.

Your odds of dying are 375 times more when flying in a firefighting aircraft than driving to work.

Is it worth it?

ESA Revision Proposal

Report released today by a group of House Republicans for updating the Endangered Species Act:

Endangered Species Act Working Group

From the report:

This Report summarizes the findings of the Working Group and answers key questions related to those findings. The Report acknowledges the continued need for the ESA, but recommends constructive changes in the following categories:

* Ensuring Greater Transparency and Prioritization of ESA with a Focus on Species Recovery and De-Listing

* Reducing ESA Litigation and Encouraging Settlement Reform

* Empowering States, Tribes, Local Governments and Private Landowners on ESA Decisions Affecting Them and Their Property

* Requiring More Transparency and Accountability of ESA Data and Science

Timber Changes Reflect Inequality: Wood products companies have busted labor unions and pay less in taxes, all to the benefit of the 1%

The following opinion piece is from Ernie Niemi, president of Natural Resource Economics Inc. based in Eugene, Oregon.

From leaders as diverse as Barack Obama and Newt Gingrich, we’re hearing a desire to rein in the nation’s extreme inequality — inequality in incomes, wealth and political power. It’s about time. The forces underlying inequality have harmed Oregon’s workers, families and communities for several decades, and they undermine our children’s economic future.

Today’s economic inequality is staggering. The top 1 percent — 1.6 million families with incomes more than $394,000 in 2012 — currently captures about 20 percent of the nation’s total income. In contrast, from the end of World War II until 1980, that group collected only about 10 percent of total income.

In recent decades, as the nation’s total income has grown, the top 1 percent has captured an increasing share of the aggregate growth: more than two-thirds since 1993, and 95 percent of all increased income since 2009.

Inequality in Oregon shows similar characteristics. Between 1990 and 2012, the median income (half have more, half have less) of year-round workers remained essentially unchanged, at about $35,000 in 2012 dollars. Not so the richest Oregonians. Over the same period, the top 1 percent saw their incomes increase by about 40 percent, to almost $240,000.

The growth in inequality likely stems from several factors, but two stand out: the decline in labor unions and reductions in taxes. The changes in Oregon’s timber industry illustrates the importance of those trends.

Before the mid-1980s, most timber workers belonged to strong unions and the industry employed about 70,000 to 80,000 workers. Then the industry busted the unions and began cutting labor costs. It did so largely by eliminating jobs, so that it now employs only about 25,000 workers statewide.

Contrary to common belief, most of the job losses have not resulted from environmental restrictions that reduced logging on federal lands. In the 1990s, when most logging reductions occurred, for example, the Forest Service estimates that those restrictions caused only about one-third of the industry’s job losses.

Most job losses stem, instead, from management’s efforts to get rid of workers, replace workers with technology, and avoid hiring workers by shipping logs overseas.

Management also has reduced wages for the industry’s remaining workers. Before the unions were busted, the industry’s average wage was about 40 percent higher than the statewide average for all workers. Now, it has fallen to near or slightly below the statewide average.

If unions had remained in place and kept timber-industry wages 40 percent above the current statewide average, wages in the industry would be about $17,000 more per worker. Do the math.

Statewide, 25,000 loggers and mill workers lose about $425 million in wages per year. For the 3,300 wood-products timber-industry workers in Lane County, the loss is about $56 million per year.

Where does all that money go? Nobody knows for sure. It seems safe to say, though, that much of the money that otherwise would be going to middle class workers now goes, instead, to upper-income owners and managers of timber companies.

The shift has real, negative economic impacts on Oregon’s workers, families and communities. It also negatively affects our children’s future: The greater the degree of income inequality in our society, the greater the consequences if they become stuck on rungs of the economic ladder where incomes remain stagnant or decline.

The timber industry has accentuated these negative effects by obtaining tax reductions. In the early 1990s, the industry paid a severance tax of about $50 million per year on the volume of timber harvested in Western Oregon, with the proceeds going to support various types of public services. In 1993, though, it used the spotted owl’s impacts on federal logging and other arguments to persuade the state Legislature to begin phasing out this tax.

That arrangement contrasts with timber harvest taxes that timber companies — often the same companies that are doing business in Oregon — pay in Washington and California.

In Washington, for example, the industry pays a timber harvest tax dedicated to county governments. If Oregon had a similar tax, it would have provided Lane and other counties in Western Oregon with about $40 million in 2011. That amount would have filled much of the funding gap that has caused counties to lay off workers in their transportation, public safety, health and other departments.

The timber industry’s experience is not unique. The crippling of labor unions in other industries and changes in taxes at all levels of government have shifted income away from workers and middle-class families and to the very rich.

The extreme inequality we see today is not an unavoidable result of natural forces, however. It results, instead, from political decisions our parents and we made in the past.

We can reverse the effects of these decisions. We must do so if we are to arrest the growth in inequality that increasingly is producing an economy, a political system and a society of the people and by the people, but for the rich.

Ernie Niemi is president of Natural Resource Economics Inc. in Eugene.

Research survey does not support logging as beetle outbreak remedy

One of the nation’s leading mountain pine beetle experts is Dr. Diana Six, professor of Forest Entomology/Pathology at the University of Montana’s College of Forestry and Conservation. As the Bozeman Chronicle reported yesterday, “On Friday, in the online journal Forests, University of Montana pine-beetle biologist Diana Six and two University of California-Berkeley policy experts published a review of the scientific evidence to date on whether forest manipulation is effective at preventing pine-beetle outbreaks. The answer is generally ‘No.’”

One of the nation’s leading mountain pine beetle experts is Dr. Diana Six, professor of Forest Entomology/Pathology at the University of Montana’s College of Forestry and Conservation. As the Bozeman Chronicle reported yesterday, “On Friday, in the online journal Forests, University of Montana pine-beetle biologist Diana Six and two University of California-Berkeley policy experts published a review of the scientific evidence to date on whether forest manipulation is effective at preventing pine-beetle outbreaks. The answer is generally ‘No.’”

You can download the full PDF of the study here. Meanwhile, the full abstract follows below:

ABSTRACT: While the use of timber harvests is generally accepted as an effective approach to controlling bark beetles during outbreaks, in reality there has been a dearth of monitoring to assess outcomes, and failures are often not reported. Additionally, few studies have focused on how these treatments affect forest structure and function over the long term, or our forests’ ability to adapt to climate change. Despite this, there is a widespread belief in the policy arena that timber harvesting is an effective and necessary tool to address beetle infestations. That belief has led to numerous proposals for, and enactment of, significant changes in federal environmental laws to encourage more timber harvests for beetle control. In this review, we use mountain pine beetle as an exemplar to critically evaluate the state of science behind the use of timber harvest treatments for bark beetle suppression during outbreaks. It is our hope that this review will stimulate research to fill important gaps and to help guide the development of policy and management firmly based in science, and thus, more likely to aid in forest conservation, reduce financial waste, and bolster public trust in public agency decision-making and practice.

Here’s a large chunk of Laura Lundquist’s article, “Research survey does not support logging as beetle outbreak remedy” from yesterday’s Bozeman Chronicle:

Logging trees in a forest can serve certain purposes, but preventing pine-beetle damage doesn’t seem to be one of them, and policy makers should stop making such claims, according to a University of Montana researcher…..Yet politicians and agency policy makers increasingly push logging projects with the claim that they will help stop the spread of pine beetles.

During the past decade, a handful of bills were introduced each year that promise bark beetle control. That number rocketed to 13 in 2013 and included bills such as Rep. Doc Hastings’, R-Wash., Restoring Healthy Forests for Healthy Communities Act. Meanwhile, the U.S. Forest Service has a number of projects intended to ward off beetle attacks such as one in the Bass Creek area of the Bitterroot National Forest.

“We wrote this paper because we’re seeing less of an interest for policy makers to include science in policy. We don’t really have the time to write things like this but someone has to do it,” Six said. “There’s this big push to do ‘something’ and people take for granted that there’s science behind these claims. Often there is not.”

Six poured through the scientific literature for any and all studies dealing with the control of pine beetles, from direct controls, such as traps, insecticides or wholesale salvage that gets rid of infected trees, to indirect controls, such as thinning, that seek to improve the health of remaining trees to improve their odds of holding off beetle attacks.

Six points out that the problem with both types of controls is they don’t address the underlying conditions of a beetle outbreak, which is tree stress due to drought and ultimately, climate change.

“People tend to think that it’s the forest’s fault, because the trees are too thick,” Six said. “In an outbreak situation, the trees are doing worse while the beetles are doing better because of the underlying conditions.”

Direct controls are expensive and deal only with a particular section of forest, so their effect appears to be limited.

It’s actually hard to nail down the effect of various controls, Six wrote, because there has been little monitoring of forests after controls were used, in spite of the fact that the U.S. and Canadian governments have spent millions to counter recent beetle outbreaks.

In one the few large studies conducted that compared treated areas to untreated areas in Canada, results seem to show that traps and tree removal limited infestation only when beetle populations were small.

When beetle populations increase, such as during an outbreak, no treatment made any difference.

Studies showed that direct efforts to keep beetle populations down must be extensive, long-term and work only at the beginning of infestation.

Six wrote that the mechanism of thinning is not well understood as far as how it improves tree health. Many studies that record success were done right after thinning occurred and could have more to do with changes in local climate than tree health.

Six said that thinning operations that don’t diminish beetle kills are often not reported, leaving a gap in the information that could further inform scientists.

No long-term studies have looked at the effect of thinning during outbreaks.

Six noted that researchers struggle to accurately assess beetle density, which is not surprising when dealing with a flying insect the size of a grain of rice. So often, efforts to keep beetle populations low may already be too late because the population is larger than what people assumed.

During winter cold snaps, many hope that the temperatures dip low enough to kill the beetles hunkered down under the pine bark. Scientists know that temperatures need to go below minus 30 degrees and stay that low for several days to do the trick.

Six said even extended cold is no guarantee.

“Even when there’s a cold snap, there will always be some that survive. That’s what happened in the Big Hole a few years ago. Ninety percent were killed, but now they’re back,” Six said.

The paper concludes that weakening environmental laws to combat beetle outbreaks is unjustified given the high financial cost of continual treatment, the negative impacts such treatment can have on other values of the forest, and the possibility that trying to control beetles now could hurt forests as they try to survive climate change in the future.

Democratic Sen. Jon Tester’s spokeswoman, Andrea Helling, said Tester’s Forest Jobs and Recreation Act evolved out of concern over beetle outbreaks but does not argue that the mandated logging would control beetle populations.

“That said, dead trees in the urban interface are a significant fire hazard to forested communities and harvesting some of the dead trees would reduce some of the risk,” Helling wrote in an email.

———————–

NOTE: Here’s the opening paragraph of Sen Tester’s website devoted to his mandated logging bill, the Forest Jobs and Recreation Act:

“Montana’s forest communities face a crisis. Our local sawmills are on the brink and families are out of work while our forests turn red from an unprecedented outbreak of pine beetles, waiting for the next big wildfire. It’s a crisis that demands action now. That’s why I wrote the Forest Jobs and Recreation Act.”

It’s also worth pointing out that during the first two Senate Committee hearings on the Forest Jobs and Recreation Act, Senator Tester opened the hearing sitting right next to huge blown up pictures showing bark beetle outbreaks. But, hey, Sen Tester “does not argue that the mandated logging would control beetle populations” right?