Phone: 509-577-7674

Follow me on:

YAKIMA, Wash. — From spotted owls to salmon, the Pacific Northwest has been ground zero for the impacts — good and bad — of the Endangered Species Act for 40 years.

That’s the view of U.S. Rep. Doc Hastings, R-Pasco, who heads the House Committee on Natural Resources, which is considering significant changes to the landmark 1973 legislation.

“Very generally, those of us in the Northwest have been hit by impacts of the Endangered Species Act more than anybody,” Hastings said. “The economy that is based here is natural-resource based, with water, and with the timber industry, so whenever you have laws that impact natural resources, they are going to impact the economy.”

Hastings believes the law takes too much of an economic toll, leaves too much room for litigation by environmental groups and lacks an emphasis on getting species recovered and off the list. He called legislation to reform the act a priority for the year.

Proponents of the Endangered Species Act, ESA for short, say that it’s working well and that calls for reform are actually a move to weaken protections.

There are lots of proposed reforms floating around, including one sponsored by Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., which would make adding a species to the list subject to state and congressional approval, automatic delisting after five years, and require the government to pay landowners who property lost value because of the ESA enforcement.

Hastings declined to comment directly on Paul’s proposal, saying that the group of representatives who are looking into reforms is still working on identifying the specific weaknesses in the law and the best potential solutions. He did say that limiting “closed-door settlements” with environmental groups was a priority.

Hastings’ push for reforms is supported by many industry organizations, including the Washington Farm Bureau. The public policy director for the bureau, Tom Davis, said that reducing lawsuits from environmental groups and requiring sound science would help landowners gain trust in the ESA process.

The ranking Democrat on the House Natural Resources Committee, Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., said in a statement to the Yakima Herald-Republic that he doubts the proposed reforms will succeed.

“There’s the potential for balanced, reasonable compromises to modernize the Endangered Species Act based on the best available science, but unfortunately this majority does not seem interested in such an approach,” DeFazio said. “Instead, we will likely spend time debating legislation that will be cast as ‘common sense’ reforms, but will actually gut the law, and as a result will go nowhere in the Senate.”

Spotted owl, shuttered sawmills

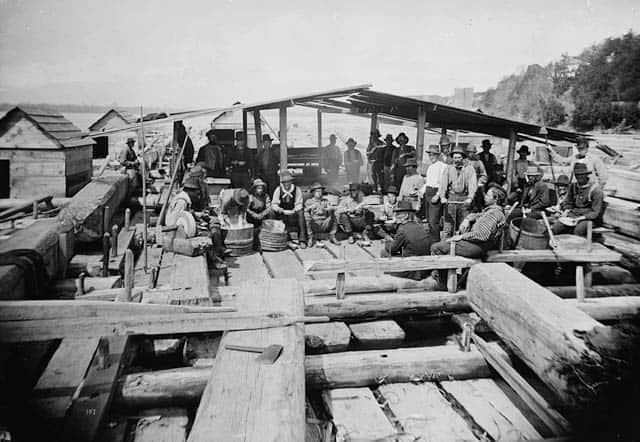

Talking about the economic consequences of the law, Hastings invokes an example familiar to many Washington — the northern spotted owl. When the iconic bird was listed as threatened in 1991, controversial protections of old growth forest were made to protect its critical habitat, reducing the forest available for logging.

Many in the timber industry blame those protections for putting loggers out of work and closing mills along the eastern Cascades.

However, other factors were also at play. Much of the most profitable acres of old-growth had already been cut at that point, and many of the secondary stands had not grown enough to log.

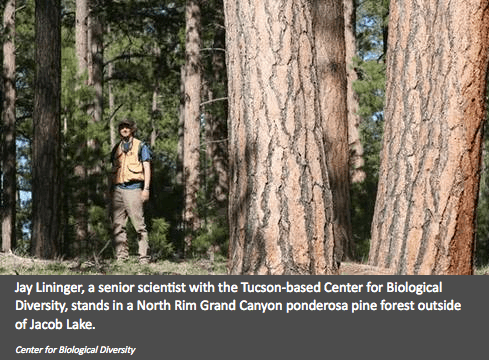

Noah Greenwald, endangered species director for the Center for Biological Diversity, disagrees with the argument that listed species are always bad news economically.

“Take the Northwest Forest Plan, which protected the last 10 percent of old-growth forest — that halted some economic activity, but the economies of Oregon and Washington have continued to grow,” Greenwald said.

Protecting endangered species, Greenwald said, actually means protecting their environments, which is important because people depend on clean water and healthy habitat just like other species.

Bridget Moran, who works for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in Washington state, said that the agency works with foresters to figure out how timber harvest and spotted owl protections can coexist.

“We work with the national forests in Washington to help them get the harvest out and more often than not, we know how to work through owl issues,” Moran said.

The ESA works, she said, because the law gives the federal agencies a flexible set of tools to solve conservation problems working with landowners.

Do we need to limit lawsuits?

The national Center for Biological Diversity is one of the environmental groups Hastings likes to blame for turning the ESA into “a process where litigation becomes more paramount than saving species.”

The Natural Resource Committee said 570 ESA-related lawsuits from 2009 to 2012 cost the federal government more than $21 million in attorney fees, including $4.6 million in the Northwest.

Hastings says time and money could be better spent working on recovery efforts.

However, the fees paid to plaintiffs in those cases do not come out of the $175 million annual budget the federal Fish and Wildlife Service has for endangered species work; it comes from a separate fund tapped for all government lawsuits.

Greenwald disputes Hastings’ contention that environmental groups sue to get listings made for “political purposes” and financial gain. They sue to force the agencies to make decisions in a timely manner, he said, not to dictate the outcome.

Last summer, Dan Ashe, the director of the USFWS, told the House Natural Resources Committee that the number of species at risk is increasing, but limited funding and a backlog of species proposed for the list means his agency can miss its own deadlines.

“Any deadline settlement we enter into commits us only to undertake a process already required by the ESA by a certain date,” Ashe said in his testimony.

He added that these lawsuits don’t give away his agency’s authority to make decisions based on the best available science.

Ashe also said a recent nationwide settlement that included hundreds of species at once was in the best interest of the public and the agency, because it allowed the agency to set priorities and achievable deadlines, while also reducing the number of lawsuits it had to deal with.

Greenwald said the right of citizens to sue for enforcement of the ESA is critical to protecting the environment.

“Hastings makes it seem like a process problem, but really, he objects to species being protected,” Greenwald said.

One listing Hastings opposed recently was that of a rare plant found in the Hanford Reach. He calls it a “poster child” for problems with the current ESA. The White Bluffs bladderpod, a perennial plant with clusters of small yellow blooms, was listed as threatened in December, despite opposition from local farmers and the Franklin County Natural Resources Advisory Committee. They hired an independent scientist to analyze the plant’s DNA to see if it really was a unique sub-species.

“The law has to be better defined as to what good science is,” Hastings said. “DNA evidence showed that it’s the same as other bladderpods. … Why was the DNA evidence ignored? In criminal law it’s conclusive.”

Federal records show that the USFWS sent that DNA study to five other scientists for review, and they all said the study lacked sufficient data to conclude that the bladderpod was not unique.

Moran said she saw the bladderpod decision as a success story because of how the agency worked with local landowners to determine the plant’s key habitat.

The only critical habitat that was designated for the bladderpod is about 2,000 acres of federal land in the Hanford Reach National Monument.

Although 300 acres of privately owned farmland was considered for habitat protection but eventually not included, area farmers still worry that the plant’s listing could cause them problems. Excess irrigation water from adjacent farms can cause landslides on the bluffs where the bladderpod grows and the USFWS could potentially limit farming in a buffer zone to protect the habitat, although there are no proposals to do so at this time.

Kent McMullen, chairman of Franklin County’s resources committee said he was “very disappointed” in the agency’s decision because of the potential impact on the area’s farmers.

“I think the USFWS is walking a tightrope trying to avoid litigation from the Center for Biological Diversity and from private landowners,” McMullen said.

He supports reforms to the ESA that would prevent agencies from wasting money on species like the bladderpod, which in his opinion don’t really justify protection, and reduce costs to landowners. However, he said he’s not optimistic that such reforms will gain traction under the Obama administration.

Salmon, steelhead success stories

When Hastings talks about endangered species success stories, he also cites a local example — salmon and steelhead restoration.

The numbers of returning salmon are improving throughout the Columbia River system, Hastings said, and he believes the specific recovery plans, written in collaboration with locals, are key to that success.

One of the 14 ESA-listed fish that travel the Columbia, the fall chinook that swim up the Snake River to spawn have grown from a run of about 800 fish in 1992 when they were listed as threatened, to 56,000 in 2013.

Stuart Ellis, a biologist with the Columbia River Inter Tribal Fish Commission, said that the Snake River chinook are one of the region’s best recoveries, thanks to the efforts of the Nez Perce tribe.

Ellis said that through ESA protections, declines have halted for all the threatened and endangered fish in the Columbia, but recovery is a complicated process and not all the species are doing as well as the Snake River chinook.

In the Yakima River, the only two listed species are steelhead and bull trout.

Alex Conley, one of the people responsible for the recovery plan process for mid-Columbia steelhead, agreed with Hastings about the value of thinking locally about how to help species.

“The cooperative approach for recovery planning for salmon and steelhead in Washington has been bringing scientists together to talk about recovery targets,” said Conley, director of the Yakima Basin Fish and Wildlife Recovery Board. “It gives you something to measure your progress again.”

Conley, who works with two different agencies for the basin’s two listed fish, because ocean-going fish fall under a different jurisdiction, said the level of local cooperation from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration led to a plan that has a lot of support and that people are excited about doing the work necessary to get the steelhead recovered and taken off the endangered species list.

If or when that happens, Hastings and Greenwald will both celebrate. But what the Endangered Species Act will look like by then remains up for debate.