Somehow I missed this on Earth Day, but here it is…note what Dan Botkin says about “drowning in information” but “sometimes the most basic information has not been gathered.”

Here’s a link and below are excerpts:

This year we will celebrate Earth Day for the 43rd time. Where have we come in those years in dealing with the environment, and how has Earth’s environment fared? I have been an ecological scientist since 1965, five years before the first Earth day. Many improvements have taken place in how the major nations deal with the environment. People the world over are much more aware of the environment, but ironically, some of the ways people think about it have not changed. There are still major gaps, concerns, confusions, and misunderstandings about ecology and the environment.

On the positive side, today in the United States we have strong environmental laws, including the Endangered Species Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Clean Air Act. The Environmental Protection Agency was created, and all the federal agencies that deal with land and water have major programs for environmental protection and improvement. Most states too have environmental protection departments under a variety of names. Non-governmental organizations, most of them small and little known in 1970, have grown into billion dollar enterprises, taken seriously by governments.

So why is it that after all this progress we have difficulty solving so many environmental problems? And why is there so much controversy about them? How could something that seems basically a set of scientific questions have been politicized and made into ideologies, to the point that each side in the environmental debates views the other side as immoral and worse? Why can’t we just engineer our planet like we do airplanes, cell phones, televisions, and automobiles? Why can’t the planet run as steadily and smoothly as the spinning blades of a hydroturbine as it produces electricity from one of our major dams?

….

We have lost touch with nature in a direct, personal sense: many of us are no longer deeply aware of nature, alert with all our senses. Although the word “environment” may be on our lips daily, few of us have the deep connection to nature that moved Cicero two millennia ago. Without that, environmental issues become abstracted, appearing as just another special interest with a backing politician, like Al Gore, telling us what to believe and whom to disapprove of.

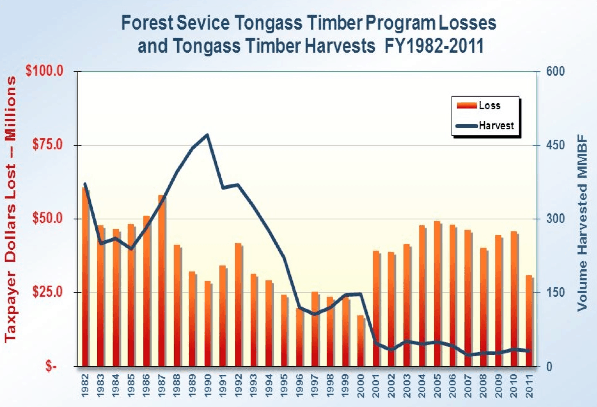

Yes, environmental issues are so popular and affect so much of our lives and economy that many spokesmen have come forward. But some of those who claim to know the truth about it have no training or experience about it. They are today’s snake oil salesmen, feeding us phrases that capture our attention on whichever environmental position they champion. As a result, we ignore many of the key issues we should be thinking about. At the moment, we are captured by climate change, our current morality play. Meanwhile, our forests and fisheries suffer from too little attention and care. Invasive species hitch rides on our commercial jets, but we ignore these dangerous traveling companions.

..

Perversely, although our information about nature has increased greatly, we hold on to the dominant fundamental myth that nature is perfect, fixed, constant, unchanging, except when we tinker with it. Our major laws and policies and even many of our scientific premises assume this constancy. Meanwhile, nature in all its forms—climate, oceans, forests, individual species—has gone on changing, has always changed.

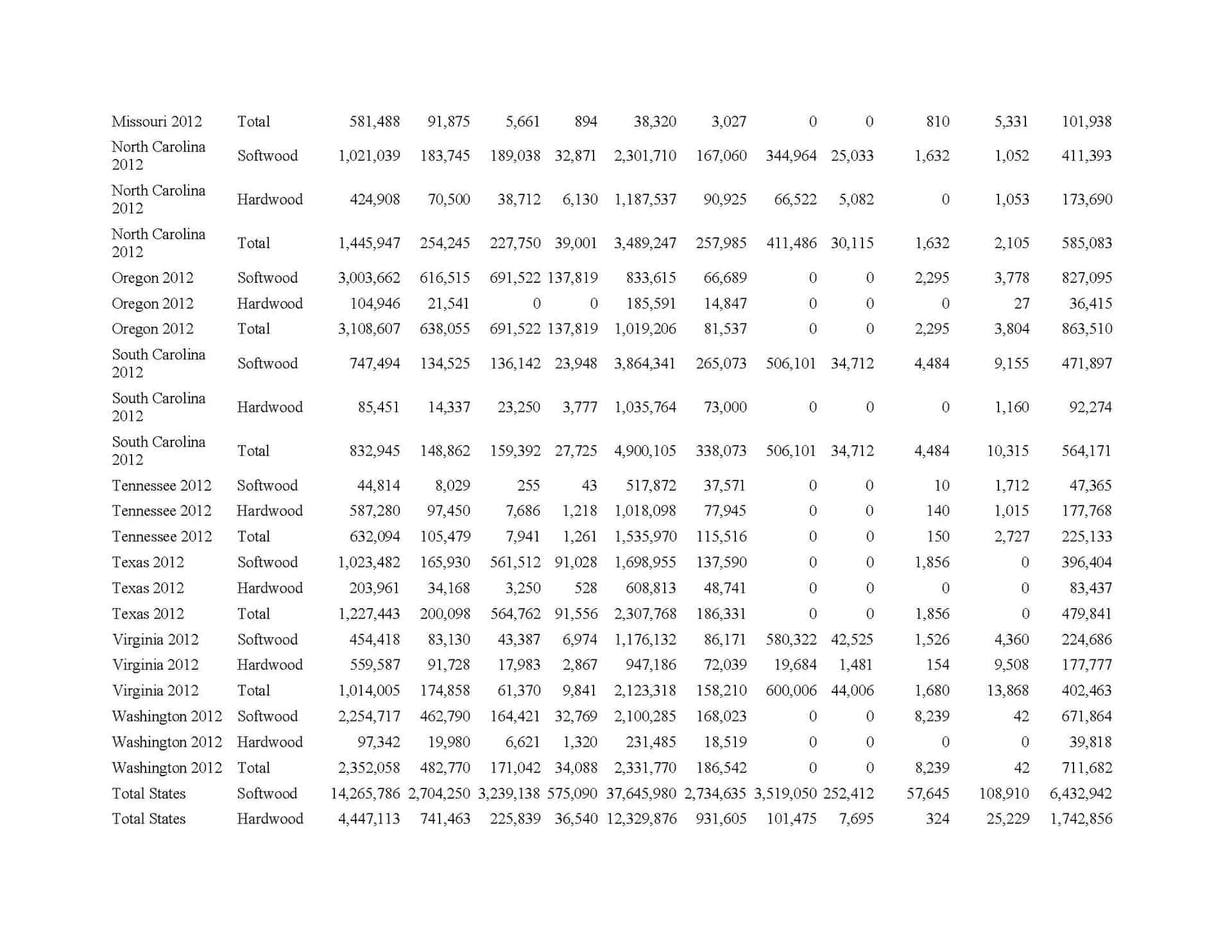

In every environmental issue I have worked on, I have been shocked to discover that although we are drowning in environmental information, some of the most basic and essential information has never been gathered. For instance, the state of Oregon passed a special bill to fund a study of the relative effects of forestry on salmon. I was asked to direct it and quickly discovered that the basic facts we needed in order to answer the question were unknown. Of the 23 rivers we were asked to study, salmon had been counted on only two. The state did not have a map of its forests. Logging permits were given by counties, which did not record the logging methods, area to be cut, or any other information necessary for an ecological assessment. All the blame for the decline in salmon was attributed to human actions though salmon live in perhaps the most changeable series of environments of any animal.

…

Does this matter? Such mistakes cost big money and lead to endless political and ideological debates without solving problems. As the leader of an environmental group in Oregon told me, “When the government said they could manage salmon, we thought that meant we could manage to have salmon.”

Unless we deepen our personal connection with nature, unless we get away from the folktales that dominate our beliefs about nature, unless we get involved and monitor what is around us, we will continue to see each environmental issue as just another political special interest and not know how to judge what is said, nor care deeply about it.

Wise words from Dan.. IMHO.

The bottom line: contact nature, think about it, feel it; seek facts, not slogans; understand science’s methods, not the catchphrases of its pseudo-spokespersons.