Went to the Zigzag Ranger District this morning for a firewood permit. The station has several “old-growth” rhododendrons that are putting on their annual show. Here are two of them. Click for a larger image. BTW, the community of Zigzag, OR, is just down the road from Rhododendron, OR.

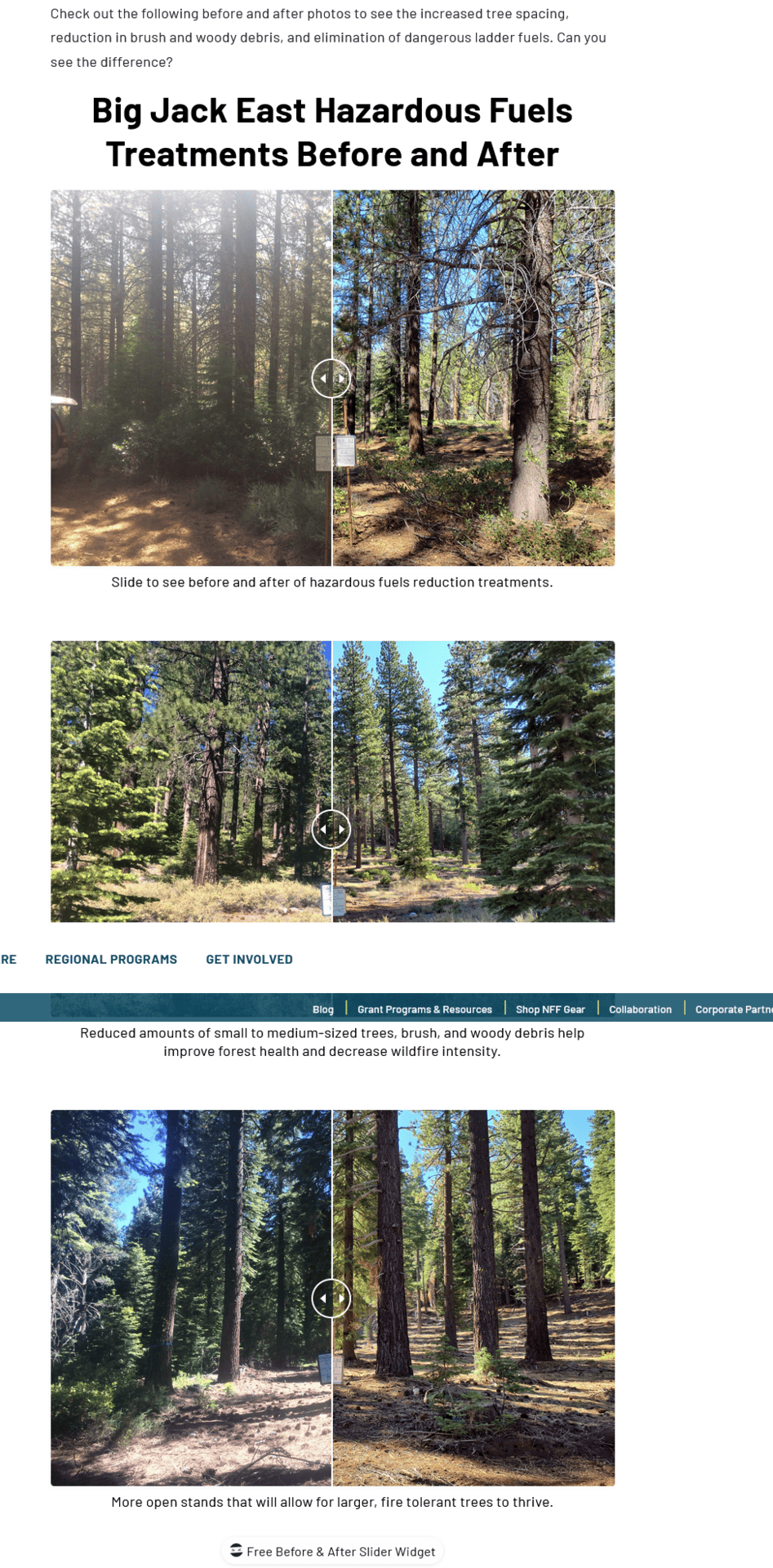

Big Jack East Hazardous Fuel Project on the Tahoe NF- Before and After Sliders and Some NEPA Stuff

I’m trying to catch up after being gone for two weeks, so if there’s something you think worthy of discussion, please post under the New Topics tab above.

Awhile back I posted some photos of fuel treatments from Oregon that were strictly not before and after on the same piece of ground.

Thanks to Nick Smith, here’s a link to a National Forest Foundation piece, which is cool because of the before and after photos of the Big Jack East Project south of the town of Truckee on the Tahoe National Forest. The project is 2000 acres.

and the fact that there is a slide feature.

Some interesting features of the decision..

It was an EA. The EA itself was 132 pages.

They have a 78 page response to comments. As far as I can tell (but they might be documented elsewhere), there were no objections.

They also have a specific document in a table that arrays “opposing science”, the name of the reference, and the response. It’s 55 pages. In this case, the scientific papers cited are very repetitive in their claims, and often referred to places outside the Sierra Nevada. I think they put an explanation in the wrong column for Opposing view 47 but I still thought it was a pretty good explanation. Perhaps the FS has a general place where folks post cited research and responses so the wheel doesn’t have to be reinvented?

Perspectives on the New BLM Rule

From Nick Smith’s news roundup today….

BLM wilderness areas may be less accessible to the public soon (Washington Policy Center)

Balanced use of public lands has been a contentious issue in the western United States for many years. A rule proposed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) would limit recreation and grazing on land previously considered public by creating a framework for “conservation leases.” The BLM manages approximately 10 percent of the landmass in the United States with much of those holdings in the West. BLM’s new director, Tracy Stone-Manning, appears to be seeking a means to circumvent Congress by proposing the change to BLM land use policy through rulemaking despite a long-standing Congressional policy already being in place.

Why does BLM need a new rule to do its job? (New Mexican)

Under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, the BLM is charged with managing the 245 million acres of public lands under its jurisdiction. That management is subject to a mandate to manage those lands for multiple uses. Historically, “multiple use” has included activities such as recreation, range, timber, minerals, watershed, wildlife and fish and natural scenic, scientific and historical values. A central feature of the BLM’s proposed Public Lands Rule is to transform “conservation” into a “use.” That is, under its proposed rule, the BLM will issue “conservation leases.” Conservation, however, is not a use. It is an objective. The BLM should already have been managing “uses” on our public lands in a way that promotes conservation. Has it? If not, why not? Why, as BLM claims, is a new rule going to make it more efficient or allow it to make better decisions? What’s going on? What’s the real agenda? Who’s behind it?

The Forest Service role in fire adapting communities

It’s rare when I run across reporting about the Forest Service taking an official position on development of private land. Yet the importance of doing so is increasing in a world where more frequent and dangerous wildfires on national forests are affecting human developments. Here is one of those rare examples.

Grand Targhee Resort in Idaho has proposed adding cabins to its base area of private land, 120 acres surrounded by the Caribou-Targhee National Forest. This has been controversial, in particular because of concerns about limited access and how the Resort would plan for and respond to wildfire. The Forest Service has expressed concerns to the county commissioners about the ability to fight wildfires there.

Asked where Targhee fell in his list of wildfire priorities, Jay Pence, Teton Basin District Ranger for the Caribou-Targhee National Forest, said the resort was “towards the upper end.” “It’s always been that way,” Pence told the Jackson Hole Daily. But, he added, “the new development just adds additional people and additional values at risk.”

To mitigate wildfire risk, Pence asked commissioners to require a few things of Targhee. It would be “helpful,” Pence said, to have “a clear and agreed-to emergency plan for the entire resort” as well as a “loop road” within the resort, and more information about “how the entire development is envisioned to be constructed.” He also asked for fuels reduction work to be done while the cabins are built. And Pence asked commissioners to “insist” on a 300-foot setback from the U.S. Forest Service’s property line, hoping to prevent the forest from having to clear vegetation on public land to protect the cabins from fire.

But Pence said any fuels reduction done on the forest will require separate permitting under the National Environmental Policy Act. It would likely require a separate analysis from the ongoing analysis of Targhee’s request to expand its boundaries.

This commercial development of an inholding is kind of an extreme case, but the kinds of things the Forest Service is asking for should be considered in any WUI development. The National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy identifies “fire adapted communities as one of three goals, and “Protecting homes, communities, and other values at risk” as one of the four “broad challenges. The Forest Service has a “Fire Adapted Communities Program,” which includes “tools of fire adaptation” like, “Wildland urban interface codes and ordinances can define best practices for construction and location of new development in a WUI community …”

I would like to know if there is also any agency guidance for Forest Service land managers for how to promote achieving these desired outcomes. They need to be able to effectively participate in local planning for private land developments that will become “values at risk” for national forest fire management. This ranger is doing the right thing, but is there any agency leadership that would encourage more of it?

Public Lands Litigation – update through May 12, 2023

CLEVER HEADLINE AWARD: “C’est levee: Coconino NF has no plans to repair Lower Lake Mary levee.”

FEATURED RECOMMENDATIONS

Some federal court cases are heard by a “magistrate” judge, who then makes recommendations to the judge who will formally issue an opinion. I haven’t often seen the judge change the recommended outcome of a case. (Maybe someone can explain this a little better.) There are two very interesting recommendations pending that I am aware of. Both would deny motions to dismiss by the agency.

Magistrate’s recommendation in Cascadia Wildlands v. Adcock (D. Or.)

On April 21 the magistrate recommended to the district court that it not dismiss this NEPA challenge to Oregon BLM’s Siuslaw Harvest Land Base Landscape Plan and EA. The BLM undertook the Landscape Plan pursuant to the Northwest Resource Management Plan (“RMP”), and it lays out a multi-decade strategy for timber harvest, but does not authorize particular projects. Standing to sue is routinely established by environmental groups for public land litigation. However, the BLM argued here that plaintiffs did not have standing because the Landscape Plan is a programmatic decision, and does not decide precisely where within the project area the BLM will ultimately log, and it therefore cannot cause an imminent injury to Plaintiffs.

The magistrate disagreed: “An agency need not have authorized an implementation action for a court to find that an area will surely be affected where “there is no real possibility” that agency will not pursue any site-specific projects under the planning framework.” Even though specific units had not been selected, the decision represents a commitment because the EA states that the agency would not be authorized to elect a non-logging alternative for a specific project because it “would not be in conformance” with the RMP. Plaintiffs were not required to tie their injuries to specific units within the project area to establish standing, so the plan’s lack of site-specificity did not prohibit them from establishing standing. The claim should also be considered ripe for judicial review because “the imminence or occurrence of site-specific action is irrelevant to the ripeness of procedural injuries (such as NEPA violations), which are ripe and ready for review the moment they happen.”

(This “program” appears to be similar to “condition-based” management “projects” in the Forest Service, but it’s less clear there would be no additional NEPA for specific projects.) (The article includes a link to the recommendation.)

Magistrate recommendation in Blue Mountains Biodiversity Project v. Wilkes (D. Or.)

In October, 2022, plaintiffs challenged the South Warner Project on the Fremont-Winema National Forest for employing the Eastside Screens amendment adopted in January, 2021 (which is under separate litigation). Although the Ochoco National Forest Supervisor was initially listed as the Responsible Official for the amendment, the Decision Notice was signed by then-Under Secretary for National Resources and Environment James Hubbard.

On April 27, the magistrate judge concluded that, “When the Under Secretary is not involved with a proposed plan amendment before signing a Decision Notice, the Under Secretary cannot later retroactively claim that the Under Secretary proposed that plan amendment by simply signing the Decision Notice,” and doing so, “does not exempt a lower ranking official’s proposed plan amendment from the objection process.” (Objection regulations create this exemption if the Under Secretary “proposes” an action. The failure to allow objections is also part of the broader Eastside Screens lawsuit.) (The article includes a link to the recommendation.)

THE MONTH OF THE (WILD) HORSE

New lawsuit: Horses of Cumberland Island v. Haaland (N.D. Ga.)

On April 12, animal rights groups and a Cumberland homeowner sued the National Park Service seeking removal of Cumberland Island National Seashore’s feral horses. The NPS management has allegedly caused harm to both the horses and the natural resources of the Seashore, violating the National Park Service Organic Act, Wilderness Act and Endangered Species Act (related to loggerhead sea turtle critical habitat.)

New lawsuit: Center for Biological Diversity v. U. S. Forest Service (D. Ariz.)

On April 27, the three wildlife-oriented organizations and three sportsman’s groups sued the Forest Service over its management of wild horses along the Salt River on the Tonto National Forest. The parties allege that the Forest violated NEPA by failing to consider the environmental impact of a 2017 agreement (and a February update) with the Salt River Wild Horse Management Group that allegedly allows continued overgrazing to harm wildlife species. The carrying capacity has been found to be as low as 20 horses, and the current population is estimated to be as high as 600. (The article includes a link to the compliant.)

New lawsuit: American Wild Horse Campaign v. Stone-Manning (D. Wyo.)

On May 10, a coalition of wild horse advocates, environmentalists and academics filed suit against the U.S. Department of the Interior over a land use plan amendment that would eliminate 2.1 million acres of wild horse habitat in the Red Desert area of and slash by one-third the allowed population of wild horses in the state Wyoming. The plan allegedly violates the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act, the Administrative Procedure Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act, arguably to promote livestock grazing. (The article includes a link to the complaint.)

OTHER LITIGATION

Supreme Court accepts Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo

The Supreme Court has announced that it will hear a case about commercial fishing rules, which could have far-reaching effects on federal agency discretion to implement laws. The Court will consider repealing the “Chevron Doctrine,” which states that courts should defer to the government’s experts’ interpretation of ambiguous statutes. Much of the concern is about the future ability of government agencies to regulate the private sector, and the effect on land management agencies may be less obvious. However, the Chevron Doctrine has been used in relation to the Forest Service’s interpretation of its Organic Act, the Wilderness Act, ANILCA, and the Clean Water Act. At least one court has granted Chevron deference to the Forest Service interpretation of NFMA (public comment requirements), and NEPA (interpretation of “extraordinary circumstances”). The Fish and Wildlife Service’s interpretations of the Endangered Species Act could also be affected.

New lawsuit: Center for Biological Diversity v. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (D. Ariz.)

On May 4, the plaintiff sued the Fish and Wildlife Service for failure to respond to its 2019 petition to prohibit all use of pesticides in critical habitat for listed species unless it has previously consulted with the Environmental Protection Agency to assess the pesticides’ impact on listed species (or if the pesticides are used to control invasive species or promote human health and safety). The lawsuit complaint asks the court to order FWS to respond to the petition within 90 days. (The article includes a link to the complaint.)

Court decision in Neighbors of the Mogollon Rim v. U. S. Forest Service (9th Cir.)

On May 5, the circuit court reversed a district court decision and partially vacated the EA (with respect to the pasture at issue) used by the Tonto National Forest to authorize grazing on several allotments, parts of which had been vacant for many years. The court held, “The Forest Service failed to give full and meaningful consideration to plaintiff’s proposed alternative, which maintains the status quo as to the closure of the Colcord/Turkey Pasture to grazing.” The court rejected the Forest Service defense that it was unnecessary because it was “within the range of” the two alternatives considered (action and no-action). It also rejected the agency’s attempt to assign responsibility to neighboring landowners for the effects of trespassing cattle on their lands in the NEPA analysis. (The article has a link to the unpublished memorandum opinion.)

New lawsuit

On May 5, the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation filed a federal lawsuit accusing state agencies of racially discriminatory conspiracy to prevent the tribe from purchasing ancestral land just outside its reservation. In 2018, the Utah School and Institutional Trust Land Administration put it up for sale, but plaintiffs allege (based on a whistleblower account) that their winning bid was undermined by the losing bidder, the Utah Department of Natural Resources who wanted to manage it as a wildlife preserve with public access.

Notice of intent to sue

On May 8, The Center for Biological Diversity and Cascadia Wildlands notified the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), of their intent to sue with regard to FEMA’s decision to fund the repair and reopening of Cook Creek Road in the Oregon Coast Range. They are concerned about Oregon Department of Forestry timber sales that would be enabled by the project, and their effects on Oregon Coast coho and marbled murrelets, both of which are protected as threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. (The article includes an indirect link to the notice.)

Notice of intent to sue

On May 10, The State of Idaho sent a notice of intent to sue to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service over the Biden Administration’s failure to remove grizzly bears from the endangered species list. The State had previously submitted a petition to delist the grizzly bears because the 1975 listing decision applies the ESA’s protections to an entity that is not a “species” as defined by the Act because it applied only to the “lower 48” population. (This article includes a link to the Notice.)

Notice of intent to sue

The Flathead-Lolo-Bitterroot Citizen task force has sent a 60-day notice of intent to sue the United States Fish and Wildlife Service as well as the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks because it says that as the state expanded trapping, snaring and hunting regulations, it failed to take safety precautions that would protect grizzly bears.

LEGISLATION

The 2018 appropriations bill exemption of forest plans from Endangered Species Act consultation when a new species is listed or critical habitat designated, which resulted from the “Cottonwood” litigation over Canada lynx, expired in April. On March 23, The House of Representatives held a hearing on a bill that would specify there is not a need to reinitiate such consultations. A similar bill was introduced in the Senate last session but not considered by the full Senate. The attorney behind the Cottonwood decision discusses this legislation here.

On May 11, the U.S. Senate passed two Congressional Review Act (CRA) resolutions that would do Biden-administration rules implementing the Endangered Species Act. One was the listing of the northern long-eared bat, and the other allows consideration of future conditions when designating critical habitat. According to Defenders of Wildlife, along with a recent similar resolution involving the listing of the lesser prairie chicken the CRA “has never previously been used on the Endangered Species Act.” President Biden has vowed to veto both resolutions should they pass the House.

OTHER THINGS

FWS response to Desert Survivors v. U. S. Department of the Interior (N.D. Cal.)

On April 27, the Fish and Wildlife Service announced that it is reinstating its 2013 proposed rules to list the Bi-State distinct population segment of greater sage-grouse as threatened under the Endangered Species Act and to designate critical habitat, and that it is reopening the comment period. The court had vacated the agency’s withdrawal of this proposed rule in March, 2020. Species proposed for listing must be addressed in land management agency decision-making where they are present

The Wyoming Supreme Court has upheld Albany County’s 2021 approval of the proposed Rail Tie Wind Project on private land by rejecting a local landowner’s bid to block the project. The challenge was to the county permitting process rather than the federal EIS, and garnered objections from close to 50 local landowners. Alternative energy will clearly not be immune to NIMBY challenges. (The article includes links to other news about Wyoming’s transition to renewable energy.)

Are large, eastside grand firs friend or foe?

A new release from a some of our favorite authors about the proposed amendment to the Oregon and Washington Eastside Screens forest plan requirements – the “21-inch rule.” The primary focus is summarized here (and there is a link to the research paper):

“Interest is growing in policy opportunities that align biodiversity conservation and recovery with climate change mitigation and adaptation priorities. The authors conclude that “21-inch rule” provides an excellent example of such a policy initiated for wildlife and habitat protection that has also provided significant climate mitigation values across extensive forests of the PNW Region.”

Until I saw this photo, I had imagined an army of evil grand fir trees sneaking up under pines and larch, and stealing their water and threatening to burn them up. They seem to be the Forest Service’s Enemy #1 these days in eastern Oregon and Washington. So dangerous, in fact, that the agency undertook another dreaded forest plan amendment process to give the agency more weapons to fight off this scourge.

This paper portrays them in a much different light, as providing benefits to both carbon storage and resilience to fire (along with their original wildlife protection benefits targeted by the original Eastside Screens amendment) – and NOT posing a substantial barrier to fuel treatment.

“The key rationale for amending the 21-inch rule is that increased cutting of large-diameter fir trees (≥53 cm DBH and <150 years) is needed to facilitate the conservation and recruitment of early-seral, shade-intolerant old ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and western larch (Larix occidentalis) by reducing competition from shade-tolerant large grand fir (Abies grandis) (USDA, 2021).

This represents a major shift in management of large trees across the region, highlighting escalating tradeoffs between goals for carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change, and efforts to increase the pace, scale, and intensity of cutting across national forest lands. The potential impacts of removal of large grand fir on wildfire are unclear, although a trait-based approach to assess fire resistance found that the grand fir forest type had the second highest fire resistance score, and one of the lowest fire severity values among forest types of the Inland Northwest USA (Moris et al., 2022).

Large ponderosa pine co-mingle with large grand fir about 14% of the time (259 plots), leaving 86% of plots with large ponderosa pine without large grand fir (1616 plots). Similarly, large western larch co-mingle with large grand fir about 56% of the time. Large ponderosa pine and grand fir are found together on only 8% of all plots in the region, while large larch and grand fir are found together on only 4% of all plots in the region. (I added the emphasis for clarity.)

Enhancing forest resilience does not necessitate widespread cutting of any large-diameter tree species. Favoring early-seral species can be achieved with a focus on smaller trees and restoring surface fire, while retaining the existing large tree population.”

If nothing else, these conclusions clearly refute the Forest Service argument that reducing fire risk is “impossible” without logging the few (but important) large grand fir trees.

A conversation with Forest Service Chief Randy Moore

Jim Petersen’s Q&A with Chief Moore is worth reading….

A conversation with Forest Service Chief, Randy Moore

In this interview, Chief Moore discusses the challenges he faces, including some that will remain challenges long after he retires.

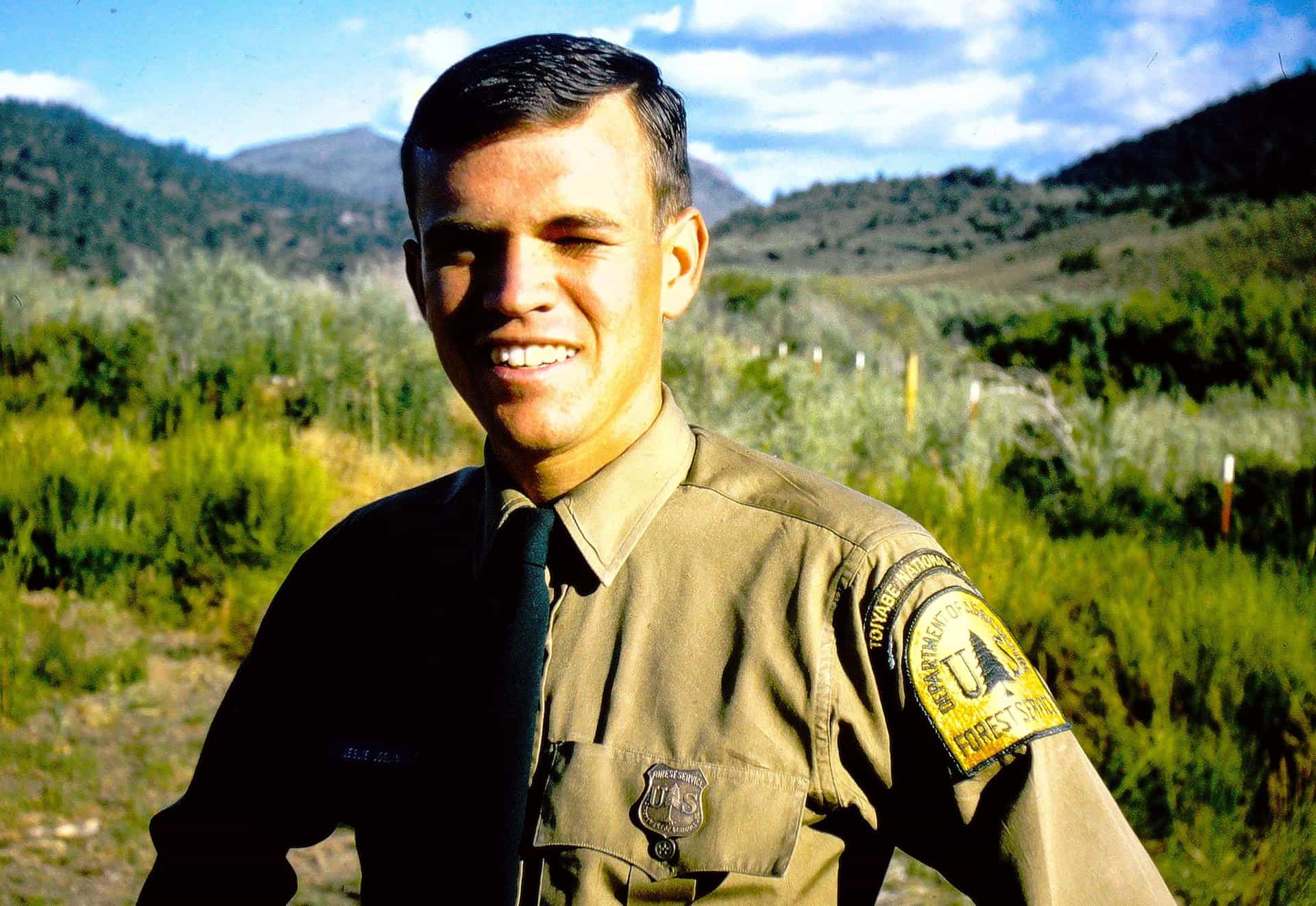

A Fire Prevention Guard Philosophy

Although my old “fire prevention guard” job title has been superseded by such titles as “fire prevention technician” or “fire prevention specialist” in ensuing decades, I think my approach to the job as I did it on the Toiyabe National Forest in the 1960s—my philosophy regarding how to do the job—remains valid.

I don’t know that any fire prevention guard ever prevented a fire just by riding around in his or her agency vehicle. I know I didn’t because I didn’t. The key to fire prevention patrol success is public contact, and the key to public contact is to get out of the patrol rig and talk with people.

So, instead of just driving through campgrounds and raising dust, I routinely parked my vehicle and walked the campgrounds. That made me available to visitors, either to initiate conversations or to respond to questions. Outside developed campgrounds, I parked a respectful distance from and walked into camps to greet campers, answer questions, and work a fire prevention message and a campfire permit check into the conversation. I did the same along heavily-fished streams or wherever else I encountered forest visitors.

Another way I made myself available to the public was by patronizing resort restaurants along my patrol routes. This cost me more than packing a lunch, but it was a rare noon hour at the Crags Resort or Mono Village restaurants in the Twin Lakes area or at the Virginia Lakes Resort restaurant that I didn’t make at least a few good contacts. I even lunched in sheep camps with hospitable Basque sheepherders a few times.

Availability’s partner in the public contact business is visibility, and I made it a point to look the part, to be easily recognized as a Forest Service representative. A good haircut and a clean shave, a freshly-pressed uniform shirt with badge and nametag in place, clean green jeans and solid work boots, all coupled with a pleasant disposition, project a positive image. There is no place in public service, I agreed with the district ranger and the fire control officer, for slovenly appearance and bad manners. I’ve no proof, of course, but I’m convinced this friendly, helpful, face-to-face approach contributed to my success at the job.

Availability and visibility were enhanced by other patrol route chores. Chief among these was sign installation and maintenance. I often left the ranger station on patrols with new road signs or fire prevention signs to be installed lashed to the rig. In addition to the tank-pump unit and fire tools, there were digging tools, paint brushes, and a five-gallon can of brown stain to help keep all district signs looking fresh. Since signs were almost always along roads or at trailheads, I was available and visible and made valuable public contacts while installing and maintaining them. This approach, I’m convinced, made a positive impression.

And, early on, I learned that—while my primary job was fire prevention—I was expected to know just about anything anyone might want to know about the Toiyabe National Forest and the surrounding country. I made it my job to be a fast learner! And what I knew I supplemented by reference to national forest maps I carried and provided—free of charge in those days—to the public. Assistance to visitors in emergencies, it goes without saying, also was part of the job.

I often wondered just how I was doing at the job. It didn’t seem enough to be told I was doing a good job. I had questions that wouldn’t answer, questions I had to answer for myself. Was my approach to each situation a good one? Did each face-to-face encounter reflect the right mix of diplomacy, empathy, and helpfulness? Was my image one of fairness and competence? Just what kind of impression did I leave with the public? It seemed I was in a position to make good friends or bad enemies for the Forest Service on a daily basis.

Did I worry too much about such things? No, I decided, I didn’t. My job was more than preventing and suppressing forest fires. It was also to win friends for and understanding of the Forest Service and its endeavors. The way I did my job helped mold public opinion of the organization in which I had always wanted to serve.

That’s why I had to be careful. It’s all too easy for someone whose job involves daily contact with a variety of publics—in my case, a wide range of national forest visitors and users—to forget these things, to become indifferent toward or even disdainful of the publics he or she serves. Worse yet, I knew, would be to ape the “badge-heavy” cop or act a “big shot” around these publics.

After all, these visitors and users are the citizen-owners of the National Forest System. It’s “national forest land” that belongs to the people of the United States and is administered for them by the Forest Service, not “Forest Service land.” A small point? A nit-pick? Not at all! It’s an all-important distinction that informs—or should inform—the perceptions of both the public servants and the publics they serve of their respective roles, responsibilities, and prerogatives regarding the national forests and each other.

Although most of the people I met were middle-class California suburbanites, visitors to the Toiyabe National Forest came from all parts of the nation and the world. All deserved the best and friendliest service I could provide. I learned then, and believe still, that pubic service means just that.

Adapted from the 2018 third edition of Toiyabe Patrol, the writer’s memoir of five U.S. Forest Service summers on the Toiyabe National Forest in the 1960s.

Blogging Break, Crown Shyness and Grid Experts

I’m taking off for two weeks and Steve Wilent has graciously volunteered to administer TSW in my absence.

- I ran across this about “crown shyness- see photo above.

- The experts in this essay by a grid expert sound like the ID team from Hell. Working on a fuel treatment project, for example, sounds mild by comparison. And this is when the experts agree on the ultimate desirable outcome!

“Utilities Are Not Experts, But Rather a Collection of Experts

There is not a common single body of expertise commonly shared by the many experts that make up an electric utility. Rather than are many experts with differing areas of expertise with demands that can place them at conflict with those operating within other areas of expertise. Effectively managing an electric utility is highly dependent upon balancing the input of many competing “experts”. The goals and priorities of large areas such budgeting, rates, maintenance, operating, environmental, planning, construction, compliance, marketing, R&D, legal, strategic planning. as well as sub areas within these, will often be in conflict as to the actions a utility should take. Leaders have to weigh the inputs from these areas to provide direction and make decisions.

Competing Experts and Goals

Healthy competition is good and necessary. The goals of maintenance are worthwhile, but sometimes in order to best utilize our resources and address other concerns, utilities might need to temporarily depart from what the maintenance experts advocate. The experts in projects tell us how long it should take to complete a project. But in emergencies, other experts might insist that this project must be completed in a much shorter time frame to allow for an upcoming summer peak. Transmission planning and distribution planning experts within the utility might favor different solutions for correcting an area problem: do you beef up the area distribution or do you add more support from the transmission system? With conflicts of this sort, sometimes you find a compromise, but in others one set of experts must give in.

***************

Specialization and Silos

In additions to problems of breadth of expertise, problems around specialization also confound attempts at expert consensus. Understanding the full extent of emerging grid reliability problems requires an understanding of generation planning, transmission planning and systems operations. Intermittent, asynchronous wind and solar energy sources impact generation planning, transmission planning and system operators. These three areas have differing expertise and experts within these areas that are not always well informed of the concerns of the others. Generation planners are concerned with providing generation 24 hours a day 367 days a year far into the future. They assume transmission planners will take care of delivery problems. Generation modelling is focused on energy production and they look at megawatt-hours. Transmission Planners are worried about the transmission system during peak times of stress. They make efforts to understand the implications of potential generation, but intermittent sources make that challenging. Their focus is based on demand levels so they look at megawatts. System Operators worry about issues of generation and transmission but they operate day to day and in the near term. Their focus is on dealing with the system as it is, not determining what it might be or handle scenarios in the far future. Further within these areas, there are specialists who go deep and do not well understand the problems within their own broader area.”

Fuelbreaks or Maybe PODs? USDA Press Release on Funding for Fuelbreaks

My idea was to stand down plan revisions due to the wildfire emergency/crisis, and have each fire forest focus on a wildfire plan amendment which would figure out PODs, areas and practices for prescribed fire and wildfire use, and also be the final NEPA point for POD development and maintenance, as well as prescribed fire projects, with an EIS. So I was hopeful that these fuel breaks are PODs.

Today, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack announced that the USDA is investing $63 million from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act to expand wildfire barriers, known as fuel breaks, to protect communities and firefighters across the West.

Fuel breaks slow a fire’s spread, create a safe zone for firefighters to work, and a safer place to conduct hazardous fuel reduction treatments like prescribed burns.

This new round of investments will support projects in Colorado, Montana, Oregon, South Dakota and Wyoming to improve firefighter response, protect critical infrastructure and natural resources, ensure clean drinking water, support local timber industries, enhance rural economies and create jobs.

“For nearly a decade, scientists at the USDA Forest Service and risk management experts have tested and refined building these defensible spaces before a wildfire starts,” said Secretary Vilsack. “With climate change fueling the wildfire crisis, we are investing in this work through President Biden’s Investing in America agenda on an even larger scale as one of the many actions we are taking to protect the people and communities we serve.”

These opportunities were identified through a cross-boundary process that brings together Tribes, local wildland fire managers, business owners, elected officials and scientists to plan for future fires. In addition to using the best available science about fire operations and risks to communities, ecosystems and responders, this process supports the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy as well as complementary fuels treatment efforts.

Through this planning process, the Forest Service works with local communities to identify fire barriers such as roads, rivers and other landscape features that can prevent wildfires from spreading. In 2015, scientists at the Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station began work with research universities, federal agencies, states, and independent land and resource management partners to identify these fire barriers in the development of wildfire strategies.

Reinforcing these barriers and constructing adjacent fuel breaks will help reduce the risk of high-severity wildfires in the project areas, all of which are in, or adjacent to, high-risk firesheds that are outside of the initial 21 Wildfire Crisis Strategy landscapes.

This announcement is part of President Biden’s Investing in America agenda to grow the American economy from the bottom up and the middle out by rebuilding our nation’s infrastructure, driving over $435 billion in private sector manufacturing investments, creating good-paying jobs, and building a clean energy economy to tackle the climate crisis and make our communities more resilient.

Learn more about how USDA is confronting the wildfire crisis on the Forest Service website.

*************

It seems like these might be a tool to settle down the folks who weren’t selected for the original landscapes. Remember in various hearings, Montana and Wyoming folks felt that they weren’t getting their share. So that all sounds good as does “the cross-boundary process”. Does anyone know where these projects are? Is there a list?