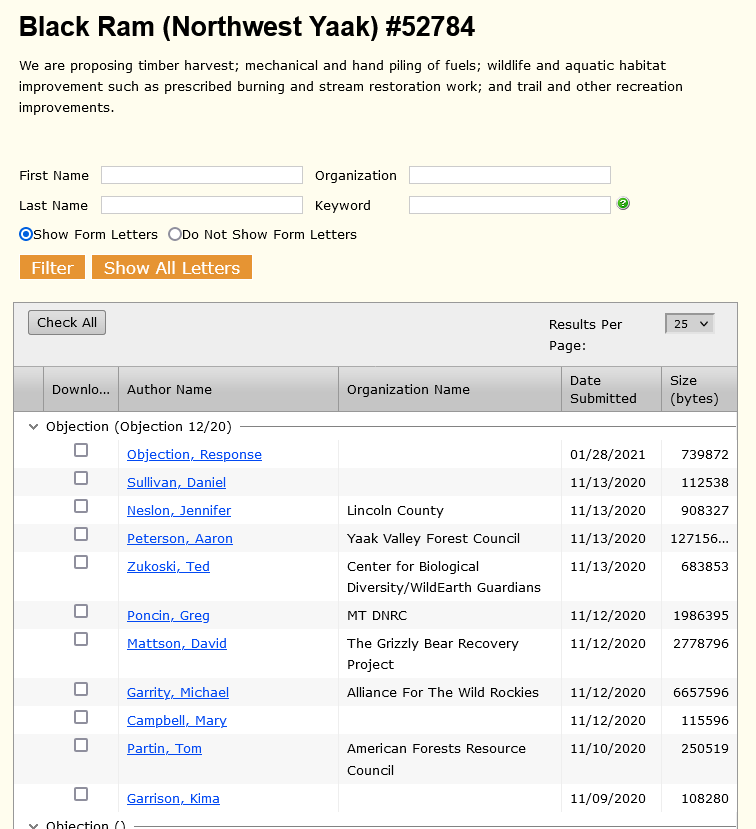

Here are the questions in the FS/BLM comment request, you can find the Federal Register Notice here.

Input Requested. The USDA Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management, DOI, are seeking input on the development of a definition for old-growth and mature forests on Federal

land, and are specifically requesting input on the following questions:• What criteria are needed for a universal definition framework that motivates mature and old-growth forest conservation and can be used for planning and adaptive management?

• What are the overarching old-growth and mature forest characteristics that belong in a definition framework?

• How can a definition reflect changes based on disturbance and variation in forest type/composition, climate, site productivity and geographic region?

• How can a definition be durable but also accommodate and reflect changes in climate and forest composition?

• What, if any, forest characteristics should a definition exclude?

Additional information about this effort, including a link to the recorded webinar, can be found at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/old-growth-forests

***********************

During our discussions of specific projects, what I found interesting about the “Mature and Old Growth” or MOG for short effort, is that in 2012 the Forest Service decided that it would manage for NRV (yes, subject to all kinds of wordy parameters, this hasn’t found its way to court yet and may not), so Forests spent all kinds of effort to analyze what NRV might look like (as I called the 2001 Planning Rule, a “full employment program for historic vegetation ecologists.”) To a greater or lesser extent informed by what Native Americans may have done with fire during various time periods. Nevertheless, here we are with forests trying to manage forest for NRV (and various wildlife species) and some projects designed for those purposes have come under attack for cutting “mature” trees. Was NRV just a analysis dead end, if the target is now “mature forest conservation”? Could everyone have just skipped that side trip? Is biodiversity for species (say oaks or western white pine, not to speak of wildlife) that require openings (and previously depended on fire) now less important than “mature forest conservation”?

Here’s my take. Certain ENGO’s have never supported cutting of trees (“logging”) for philosophical reasons. For a while, species (such as spotted owl) were a good horse to ride in pursuit of that goal. Now they are riding the “carbon” horse. However, the carbon horse has issues.

For example, as we have pointed out, old trees die. Even “mature” trees, due to bugs, fire, etc. Many people, including me, have said this. There’s even now a scientific study that says “trees may burn up or die in California and that wouldn’t be good for carbon.” I’d put my carbon money on direct air capture technologies, or if it had to be trees, then reforestation for carbon as well as meeting other objectives.

Perhaps trees and forests are going to die from climate change, so there’s that also. Climate change (may be) killing trees and forests. At least that’s the tenor of this WaPo story today. “oldest trees may not survive climate change”. Of course, these particular trees are also in one of the toughest areas for trees to start with. Time for a field trip to your local bristlecones. But if we think climate change will kill our current forests, maybe that’s not the best carbon bet.

I’m sure given all the smart people in the Forest Service, they will figure something out that makes sense. What will be more interesting is how the politics will play out across USDA, which tends to have a rather common-sensical perspective, versus the more political DOI -perhaps more beholden to the key ENGO’s, and perhaps more closely monitored by the climate folks in the White House. And the question of what an Executive Order can do vs. MUSYA and even the Planning Rule. And, of course, the timeframe for analysis, and rulemaking (?) and .. elections. Should be interesting to watch!

***********

I wrote a song parody about the Old Growth issue for the Old Growth person’s (can’t remember his name) retirement party sometime in the 90s.. I think it was an issue in HFRA. It was to the tune of “Maria” from Paint Your Wagon.

Way out West we’ve got a place

With big and fat and old trees

We’ll draw a line around the place so they won’t become..sold trees.

Reserves.. Reserves.. we call those areas.. reserves.

But old trees die and then fall down

And we’ve got premonitions

But we’ll do fine, we’ll move the lines, or change the definitions.

***********

If anyone’s interested in the history of old growth analysis in the 90’s, you can google “old growth forest service 1990” and find some regional documents.