Links provide additional information.

COURT CASES

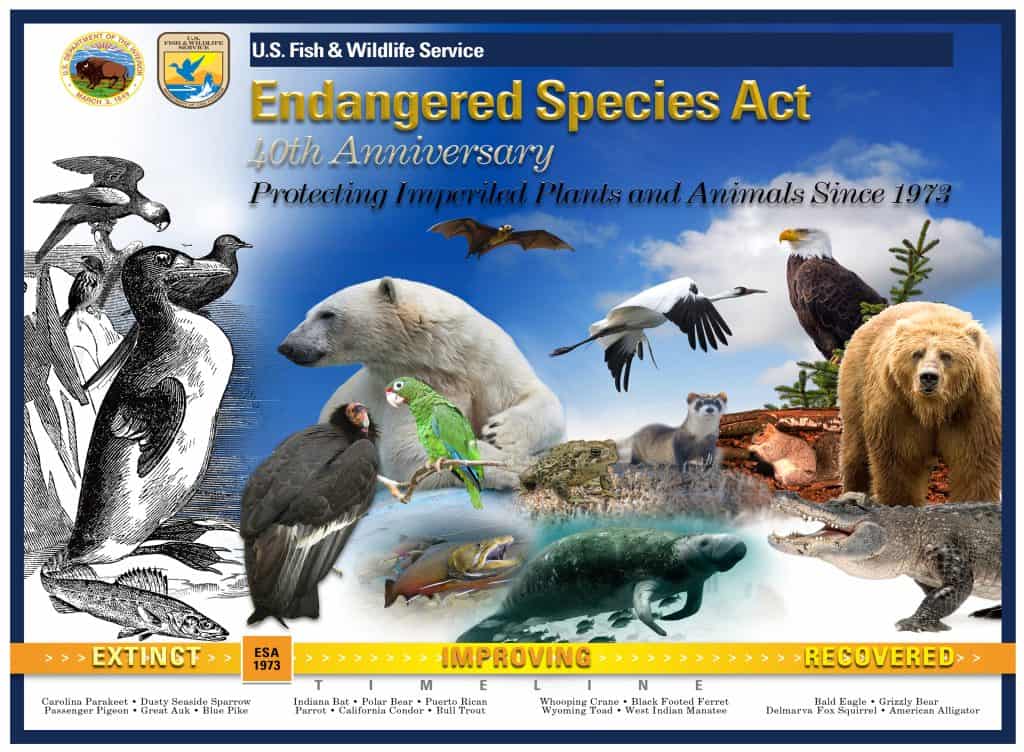

On April 15, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district court and upheld the designation of critical habitat for the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse, which is found in dense riparian vegetation in the southwest. Plaintiffs were federal grazing permittees. The court was largely deferential to the Service’s consideration of economic impacts and the benefits of excluding some areas that it had decided to include. (The opinion in Northern New Mexico Stockman’s Association v. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service is here.)

On April 19, the Center for Biological Diversity moved to intervene as a defendant in a case filed in the District of Columbia district court on December 13, 2021 by the New Mexico Cattlegrowers’ Association against the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service for denying their petition to delist the endangered southwestern willow flycatcher. The species is found in riparian forests in the southwest, and has been the subject of litigation against cattle grazing on public lands. Plaintiffs allege that the bird is not a valid subspecies that is eligible for listing.

On April 21, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a lawsuit against the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the district court of Arizona for delaying a determination of whether to list the Suckley’s cuckoo bumblebee as threatened or endangered. These parasitic pollinators were once common in prairies, meadows and grasslands across the western United States and Canada. Suckley’s cuckoo bumblebees are threatened by declines in their host species, habitat degradation, overgrazing, pesticide use and climate change. The survival of Suckley’s cuckoo bumblebees is dependent on the welfare of their primary host, western bumblebees, who have declined by 93%. The Center is also working to obtain Endangered Species Act protection for western bumblebees.

In response to three lawsuits brought by the Center for Biological Diversity, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agreed to dates for decisions on whether 18 plants and animals from across the country warrant protection as endangered or threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. The Service will also consider identifying and protecting critical habitat for another nine species. The species include the wide-ranging monarch butterfly and tri-colored bat, and two salamanders found on the Sequoia National Forest.

Another species is the eastern gopher tortoise, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will determine by Sept. 30 whether gopher tortoises in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina and eastern Alabama should be listed. Gopher tortoises are already listed as threatened in Louisiana, Mississippi and western Alabama. “The tortoises need large, unfragmented, long-leaf pine forests to survive,” the center said Tuesday in an announcement about the settlement. This lawsuit, which was filed last year in federal court in Washington, D.C., said the Fish and Wildlife Service found in 2011 that gopher tortoises merited listing because of threats “including habitat fragmentation and loss from agricultural and silvicultural practices inhospitable to the tortoise, urbanization, and the spread of invasive species.” However, they were not given a high priority for listing by the agency. (This article discusses the gopher tortoise.)

WildEarth Guardians and Wilderness Workshop have settled their lawsuit against the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service for designating insufficient critical habitat for Canada lynx (leaving out parts of Montana) in 2014. The reconsideration of critical habitat will occur by the end of 2024. This comes after the Biden administration reversed a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service decision to propose delisting the lynx in 2017 during the Trump administration. (Following that, another group of conservation organizations reached an agreement with the agency in November 2021 to write a draft recovery plan for lynx by the end of 2023.)

LISTING ACTIONS

On March 2, the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed designating two freshwater mussel species as threatened, and also proposed critical habitat. The western fanshell is found on the Mark Twain and Ouachita national forests, and the Ouachita fanshell on the Ouachita.

Following litigation, on March 23, the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service reversed its position and proposed to up-list the currently threatened northern long-eared bat to endangered status, primarily as a result of continued losses to the white nose syndrome disease. The important change that will result is the removal of exceptions to incidental take requirements that are available for threatened species but not for those classified as endangered. This will mean more involved consultation procedures for any actions that remove trees in the 38 eastern states in which the species is found.

On April 13, The Center for Biological Diversity and two other conservation organizations notified the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service of their intent to sue for delaying a determination of whether the thick-leaf bladderpod should be listed under the Endangered Species Act. This follows the failure of the BLM in southeastern Montana to act on its staff recommendations to close an area to mining to protect this species they classify as “sensitive” from potential gypsum mining. Off-road vehicle use is also a factor. (This news release has a link to the NOI).

On May 12, the Center for Biological Diversity notified the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service of its intent to sue for delaying making listing decisions for 11 species. One of these is the whitebark pine, found at high elevations in seven western states. Two plants are threatened by cattle grazing in the southwest, and the slickspot peppergrass by grazing in southwest Idaho. The sickle darter (a fish) is allegedly affected by logging near rivers in Tennessee and Virginia.

Congress agreed to again include in its fiscal year 2022 appropriations bill the rider that prohibits the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service from listing sage-grouse under the Endangered Species Act. This language has been included since 2014, allegedly as the result of oil and gas industry lobbying. It became law on March 15.

OTHER WILDLIFE NEWS

On April 22, a county judge in Ventura County upheld two local ordinances that designate standards for development and require environmental reviews for projects that may hinder wildlife connectivity. The ordinances help protect the wildlife corridors that connect the Los Padres National Forest, Santa Monica Mountains and Simi Hills. Habitat connectivity is crucial for the survival of mountain lions, gray foxes, California red-legged frogs and other wildlife in the region, and the Forest Service participated in identifying the corridors.

The Shawnee National Forest has temporarily closed Service Road No. 345 to allow safe passage for many species of amphibians and snakes during a critical time of migration.