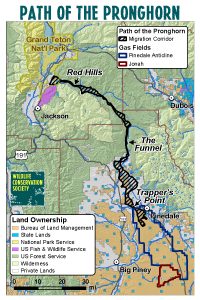

The Bridger-Teton National Forest amended its forest plan in 2008 to designate the portion of the “Path of the Pronghorn” migration corridor in Wyoming for special management to protect this historic 90-mile route with a northern terminus in Grand Teton National Park used for summer range. It’s probably the most significant action taken by the Forest Service to plan for wildlife connectivity.

The BLM chose to not play along at the southern end where major oil and gas fields are found in the species’ winter range, and the migration route lacks recognition, and protection, through BLM lands along its southern reaches. Now they have issued an EIS for oil and gas development there. Ideally, the EIS will disclose the effects on pronghorn migration and on the national park (using the best available science), which could include exterminating this migration and its pronghorn herd. But I wanted to comment on the planning aspect of this problem. BLM blames the State of Wyoming:

“It would help us out if the [Wyoming] Game and Fish were to formally designate something in there,” said Caleb Hiner, who manages the BLM’s Pinedale Field Office.

The Forest Service didn’t wait for state action to protect national forest lands. As an environmental activist said, “The BLM has all the authority it needs to protect what it wants to protect in a site-specific document,… The BLM could decide tomorrow that it doesn’t want to lease or develop any of the NPL.”

The 220-square-mile project has major economic potential, and could generate 950 jobs and produce somewhere in the range of 3 trillion cubic feet to 5 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, Hiner said. It would add up to 350 wells to the landscape annually for the next 10 years, a level of development that equals the number of wells permitted for drilling in the BLM’s entire Pinedale Field Office during 2017.

The argument by the proponent seems to be that they can figure out mitigation well-by-well, but at that point there is little opportunity to develop an effective strategy for pronghorn to navigate the system of wells, especially with no plan-level requirement to do so.

It is important for federal land managers be leaders in coordinating connectivity conservation planning, if for no other reason that that may be what is necessary to provide for viable populations of migrating species to continue to use federal lands. The absence of a plan based on an overarching strategy for the full extent of the herd’s range could now be fatal to a ecological phenomenon that has been occurring, in part on national forest lands, for thousands of years.