I thought this opinion piece would be worthy of discussion, because federal lands in the West turn out to be key to current renewable energy build-outs.

But first I’d like to back up and give a framework which I think is important to consider, especially since these are likely to be major issues in the future. Take a community composed of various ethnic groups, economic classes and so on, with surrounding landscapes. Someone want to develop something there (mines, solar and wind, geothermal, powerlines, oil and gas, dams, grizzly or wolf reintroduction) for the good of the broader population. Not to get all political science-y here but who decides what is the good of the broader population? Who decides who gets to sacrifice (however felt by locals) their own views, agriculture, land, to what end? What if some in the community benefit and others get only the downsides? How does social justice enter into the equation?

And finally, should Tribes not only have a voice, but have the ultimate say, based on their original ownership of the land and the injustice of treaties? I’m thinking here on federal lands for pragmatic reasons. With all these complexities, when Coastals start talking about NIMBYism when it comes to development of rural lands, I like to replace NIMBY in my mind with “local concerns.” As one of my fellow planning commissioners in El Paso County said.. “it’s got to go somewhere.” But does it? At the most extreme, using political force to do something locals don’t want has colonialist overtones.

Check out this Noah Smith op-ed in Bloomberg Opinion .. tagline

State and national leaders need to move more forcefully to override local protestors who are blocking new solar and wind developments under the guise of land conservation.

And for readers interested in partisan political stuff, the fellow who wrote this op-ed, Wally Nowinski, is the former democratic ads director for House and Senate Dem candidates, according to the blurb. As for me, I am quite sympathetic to the environmental groups. They want to be the “good guys” but without the traditional “bad guys” (forest products, oil and gas) the way forward is not so clear. They could be for nuclear to reduce the environmental footprint, but members probably don’t want that either. I don’t see any bad guys here, just people who want different things. Side note: in the comments it was pointed out that NRDC really hadn’t done what the author said.

Conservation is not the same thing as climate action.

Conservation is a conservative impulse, but right now, the climate threat calls for sweeping changes to our physical environment. Our best shot at mitigating the impact of climate change is to electrify every process in our economy as quickly as possible: We need to preserve clean energy infrastructure like hydro and legacy nuclear power plants. We need to build a ton of new wind and solar fast. And we need to find and harvest the raw materials needed for batteries.

All of these projects pose tradeoffs: They’re important from a climate standpoint, but bad from a conservation standpoint. To state the obvious: If you build a solar farm in the desert, it is no longer a natural desert habitat, it’s a solar farm. Meanwhile, wind farms do kill some birds. Hydro dams (though we aren’t likely to build more since we’ve already used the best sites), do disrupt fish, and nuclear plants still scare people.

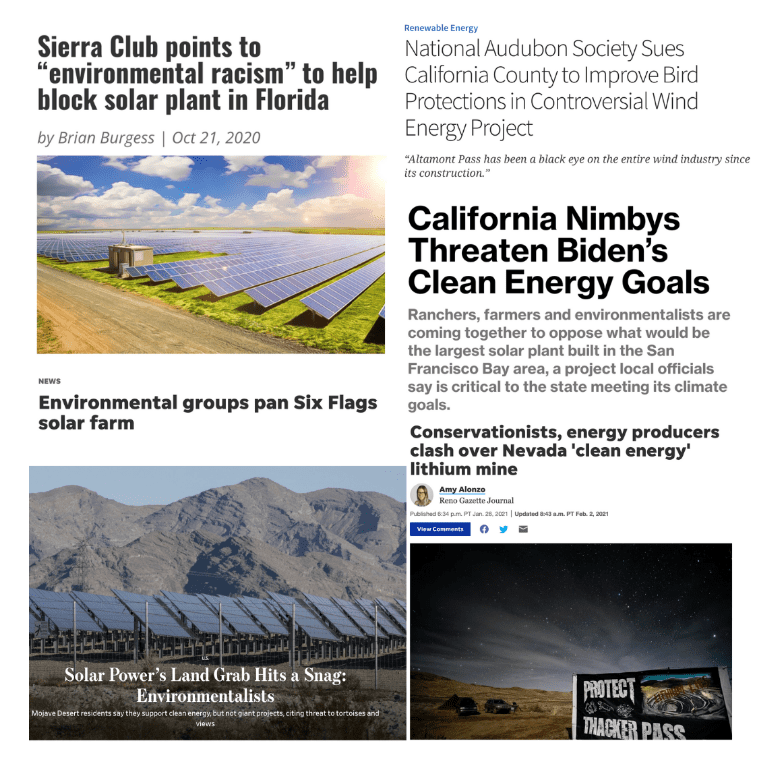

So it’s not actually surprising that conservation groups like the Sierra Club, the Audubon Society and the NRDC regularly oppose specific clean energy projects, even while they acknowledge the importance of a rapid energy transition.

The tradeoffs are a hard problem for organizations to wrestle with, particularly when many of our biggest environmental groups were founded specifically with a goal of conservation. The Audubon Society was created to protect birds and the Sierra Club was founded by mountaineers. The Natural Resources Defense Council, meanwhile, grew out of opposition to a hydro-electric project on the Hudson River. Until very recently, their agendas were focused on protecting what already existed–not embracing rapid change.

For its part, the national Sierra Club leadership seems to be trying to put more emphasis on supporting clean energy projects than it did in the past. Its platform calls for 100% clean energy now, and the organization’s national magazine even published a story about the threat NIMBYs pose to renewable energy. But when you have an organization that has fought for conservation for over 100 years, and whose entire playbook and tool kit is designed to stop or at least delay change, embracing clean energy development can be hard.

Many conservation groups have a structure that makes them chaotic, and vulnerable to NIMBYs.

One of the reasons the Sierra Club was so successful at advancing its agenda in the late 20th century is that it was organized as a chapter-based membership organization. Local chapters popped up across the country where the most passionate members could organize around local issues, lobby local politicians, and talk to the press, all with the credibility of the Sierra Club name behind them. The Audubon Society, and more recently the Sunrise Movement, followed a similar model.

This structure enabled the groups to take on many more fights than they otherwise would have, and helped broaden their influence within state and local governments across the country. Wherever you went, there was likely a Sierra Club chapter ready to weigh in on local development projects.

Now, that structure means that the groups’ power can be high-jacked to protect members’ backyards. For example, last year, the Sierra Club of Iowa came out swinging against a solar project. The weight of its message was increased by the imprimatur of the national brand—normie voters don’t know the difference—even though the national organization has said it’s pro-solar development.

The Sierra Club used to be for natural gas as a transitional fuel.. but local groups didn’t like development near them. So in that case, it was The Right Thing to be against natural gas due to the influence of locals.. or was it “high-jacked to protect members’ backyards” in that case as well?

…..

It’s not just organizations with a historic conservation mission that can be taken over by NIMBY interests either. Earlier this week the Amherst Chapter of the Sunrise Movement, a group whose tagline is “We are the climate revolution,” joined area NIMBYs in advocating for a moratorium on all large solar projects in the city.

Where do we go from here?

Big environmental groups have very powerful brands, particularly in blue states. Unfortunately, I think we should expect the trend of these organizations opposing clean energy projects to continue, at least in the short term. Because of their brand power, that opposition will carry a lot of weight, and it will likely be weaponized by conservatives and others to say “even environmentalists oppose this project.”

The solution will involve rethinking what it means to be “environmentalist.” The term is usually understood to encompass a wide range of different causes–from climate activism, to habitat conservation, to recycling and plastic straw bans. But it’s worth remembering that not everything coded as “green” helps fight climate change, and much of it is actively counterproductive.

The good news is there are some signs of an internal backlash within environmental groups. In 2019, a cadre of activists concerned about climate change took over the Ann Arbor, Michigan Sierra Club in a contentious election. In the Bay Area, different local Sierra Club chapters are fighting with each other about whether or not to support a big solar project. And while many chapters continue to be almost cartoonishly NIMBY on housing issues, the national Sierra Club changed its tune on housing construction and now supports infill development.

The most basic thing we can do now is simply to recognize we are not in an era where all environmental goals are aligned. Conservation and climate action are often directly at odds. And if we’re going to successfully prevent global calamity wrought by extreme weather and rapid warming, we’re going to have to displace many more tortoises.

In reality, developing a scheme of decarbonizing on paper is easy, and building it out is difficult. We always knew that.

““it’s got to go somewhere.” But does it? At the most extreme, using political force to do something locals don’t want has colonialist overtones.”

Well, there’s been a lot of folks looking at the no-action alternative, and it’s hard to argue that it would provide the greatest good for the greatest number in the long run. (Or is that now a “colonialist” philosophy?)

We should be asking the NIMBYs and conservation groups to tell us where these things SHOULD go. Unfortunately, we don’t have institutions set up to manage this. Except on public lands, where we have the authority and some experience with large-scale regional planning that could help answer this question. “America the Beautiful” (30 x 30) should be telling us the most important areas to not develop, and some kind of assessment could tell us the best places to develop. You could tack a social justice screen onto that, too. If this makes the greater good more obvious, the NIMBY argument is much weaker.