The second workshop of Wyoming Governor Mark Gordon’s WGA Chair initiative, Decarbonizing the West, will be held in Boise, Idaho, on December 12 and 13.

The two-day workshop will focus on topics related to natural carbon sequestration, including agriculture, forestry, and land management. It will feature roundtable discussions with carbon capture experts from around the region, including the Idaho National Laboratory, as well as remarks from Governor Gordon and Idaho Governor Brad Little.

View the agenda below and register here to watch a FREE livestream of the event.

You can also watch recordings of the first Decarbonizing the West initiative workshop, which explored the potential of carbon capture, utilization, and storage technologies, here.

December 12

12:30 p.m.: Welcome and Introductions

– Jack Waldorf, WGA Executive Director

12:40: Opening Remarks

– The Honorable Brad Little, Governor of Idaho

12:50 – 1:55 p.m.: Roundtable 1: Dairy Digesters and Agricultural Waste

Digesters can significantly mitigate greenhouse gas emissions from livestock production by capturing methane that would otherwise be released from manure. The resulting biogas can be used to meet on-farm energy needs or sold on the market. This panel will explore the opportunities, challenges, and benefits for biogas recovery and how digester systems can contribute to overall emissions reduction in the agricultural sector.

Panelists: Andre Brasil, Senior Director, Business Development, California BioEnergy LLC; John Olshefski, Ingevity; and Jesse Burson, Supply Development Lead, Renewable Natural Gas, Shell.

Moderated by: Rick Naerebout, Chief Executive Officer, Idaho Dairymen’s Association

1:55 - 2:50 p.m.: Roundtable 2: Climate-Smart Agriculture

Increasing adoption rates of climate-aware practices is one of the most effective ways to reduce the effects of carbon emissions from the agriculture sector. Incentivizing new practices, compensating producers for less-efficient yields, and building demand for agriculture-based carbon markets are a few of the approaches to accelerate adoption by producers.

Panelists: Bill Jaeger, Strategic Initiatives Officer, LOR Foundation; Myles Gray, Program Director, U.S. Biochar Initiative; and Tony Schoonen, Chief Executive Officer, Boone and Crocket Club.

Moderated By: Kirsten Boysen, Managing Director, Colorado Department of Agriculture, Drought and Climate Office

2:55 – 3:50 p.m. Roundtable 3: Decarbonizing through Integrated Energy Systems

Idaho National Laboratory’s Integrated Energy Systems Program, supported by the Department of Energy’s Office of Nuclear Energy, conducts research, development, and deployment activities to expand the role of nuclear energy beyond the grid for various industrial, transportation, and energy storage applications. INL’s work on integrated energy systems and other research areas such as biomass, hydrogen, ammonia, and nuclear for heat and electricity generation can enhance utilization of low or non-emitting energy generation, bolster grid resiliency, and help achieve clean energy economy goals. The panel will discuss various decarbonization pathways and provide insights on the techno-economic and socio-economic effects of deployment on the energy economy.

Panelists: Eric Dufek, Department Manager, Energy Storage & Electric Transportation Department; Seth Snyder, Program Director, Energy, Environment Science and Technology; David Thompson, Chief Scientist, Bioenergy, Ning Kang, Department Manager, Power and Energy Systems; and Ning Kang, Department Manager, Power and Energy Systems.

Moderated by: Todd Combs, Associate Laboratory Director

4:00 – 4:55 p.m.: Roundtable 4: Carbon Storage in Mass Timber

Forests are excellent at sequestering carbon into biomass, but less effective at retaining carbon over long timescales. Stabilizing forest carbon within long-lived building materials presents a powerful opportunity to not only mitigate carbon emissions from wildfires and decomposition, but also to defray the costs of forest health treatments. Achieving these dual benefits requires growing both the supply chains for mass timber products as well as the markets for utilizing them. This panel will examine strategies for expanding mass timber utilization and its benefits for forest restoration economics and natural carbon sequestration.

Panelists: Jennifer Okerlund, Director, Idaho Forest Products Commission; Bill Parsons, Chief Operating Officer, WoodWorks – Wood Product Council; and Julie Kies, U.S. Forest Service, Wood Innovations Program Manager.

Moderated by: Rachael Jamison, Vice President, Markets and Sustainability, American Wood Council

5:00 p.m.: Adjourn

December 13

8:30 a.m.: Decarbonizing the West Initiative Remarks

– The Honorable Mark Gordon, Governor of Wyoming

8:45 – 9:40 a.m.: Roundtable 5: Balancing Carbon Stewardship Management Goals

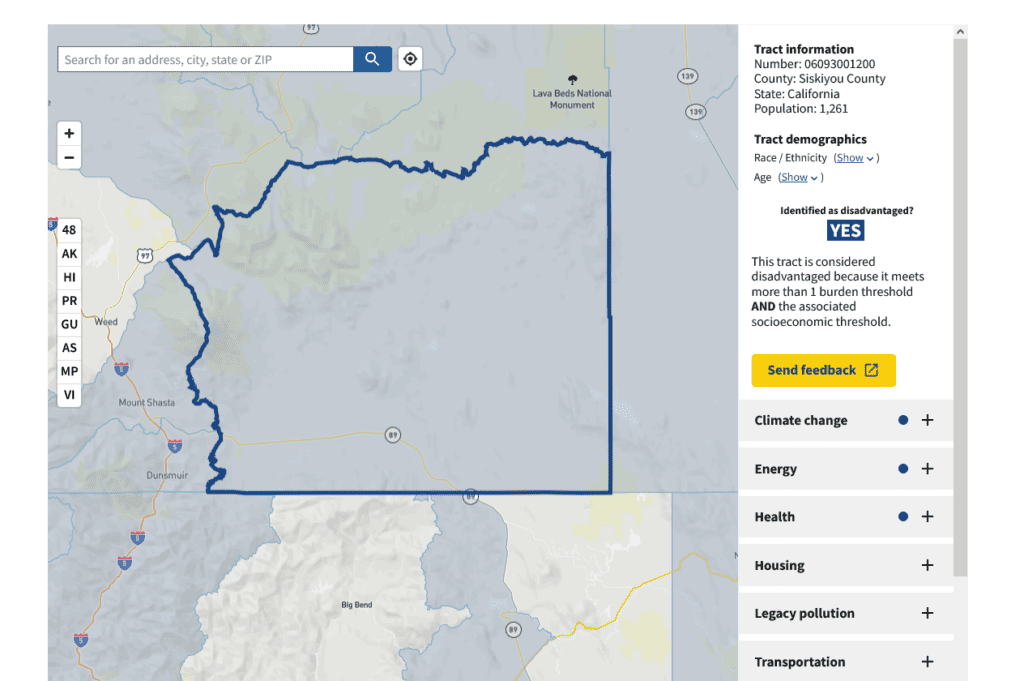

Forests and grasslands sequester about 14 percent of the United States’ carbon emissions and represent one of the largest opportunities for large-scale carbon removal. Management actions can be strategically selected to optimize carbon sequestration and storage while meeting other management objectives. This is a delicate balancing act, however, that increases the potential for unintentional outcomes. The panel will examine the nuances of carbon stewardship and the potential benefits of carbon optimization projects on forests and rangelands.

Panelists: Matt DiBona, District Biologist, National Wild Turkey Federation; Jim Elbin, Trust Lands Division Administrator, Idaho Department of Lands; and Katharyn Duffy, Director of Science Operations, Vibrant Planet

Moderated by: Todd Ontl, Climate Adaptation Specialist, U.S. Forest Service.

9:45 – 10:40 a.m.: Roundtable 6: Incentivizing Carbon Reductions

Voluntary carbon markets have emerged as a dynamic and evolving method of reducing carbon emissions. These markets allow businesses, organizations, and individuals to take proactive steps to reduce their carbon footprint. Carbon markets can drive innovation, support sustainable projects, and promote environmental stewardship. In recent years, these markets have expanded, presenting both challenges and opportunities to meet carbon reduction goals. This panel will explore the potential pitfalls and opportunities to support broader carbon dioxide reduction activities through voluntary carbon markets.

Panelists: Brian DiMarino, Head of Operational Sustainability, JP Morgan Chase; Spencer Plumb, Senior Manager, Forest Market Innovation, Verra; and Matt Bright, Director of External Affairs, CarbonCapture Inc.

10:50 - 11:45 a.m.: Roundtable 7: Innovative Finance for Carbon Benefits

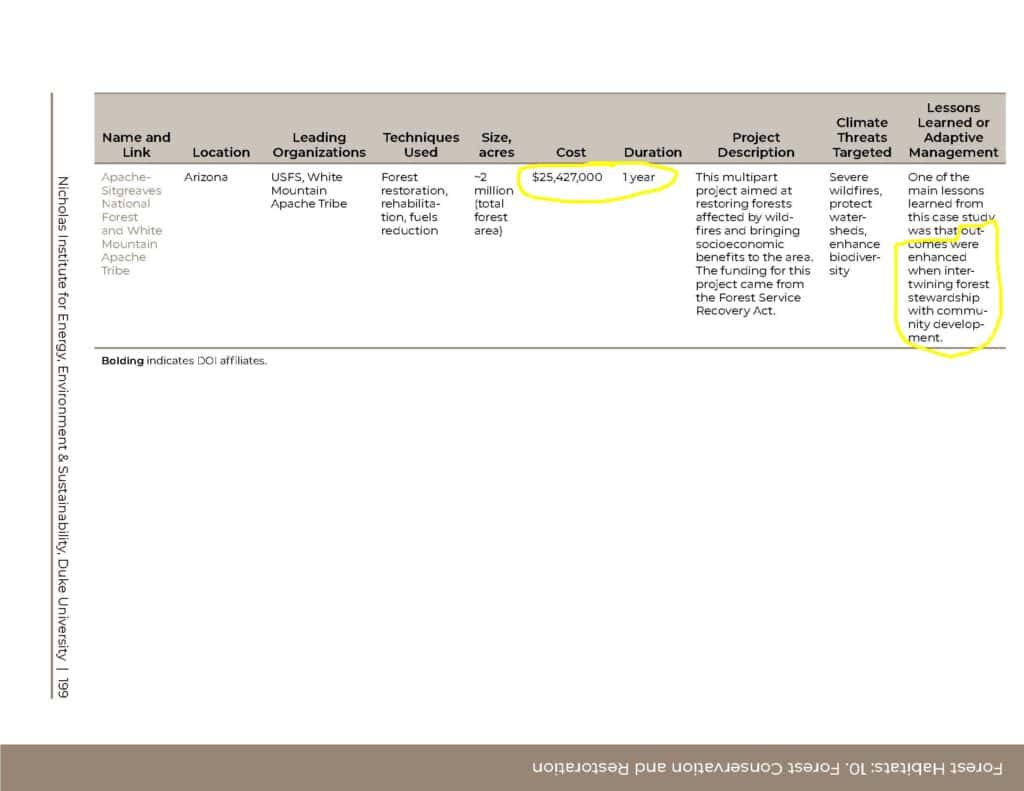

Healthy forests are a prerequisite for natural carbon sequestration, but funding can be a limiting factor for forest restoration or afforestation projects. Innovative strategies for providing forestry assistance have demonstrated that unconventional approaches can yield significant carbon sequestration benefits. Instead of relying exclusively on public resources, these strategies leverage a mixture of funding sources, technical assistance, and other resources to support forest health and carbon sequestration. In this panel, participants will discuss how innovative finance mechanisms and partnerships can catalyze investment in natural climate solutions.

Panelists: Mary Mitsos, President and CEO, National Forest Foundation; Luke Hawbaker, Director of Business Development and Partnerships, Mast Reforestation; and Jill Ozarski, Program Officer, Environment, Walton Family Foundation.

Moderated By: John Oppenheimer, Government Relations Director, Idaho Conservation League

11:45 a.m.: Recap and Takeaways