You don’t expect the Washington Post to take an interest in what’s going on in Wyoming, so this story was something of a surprise.

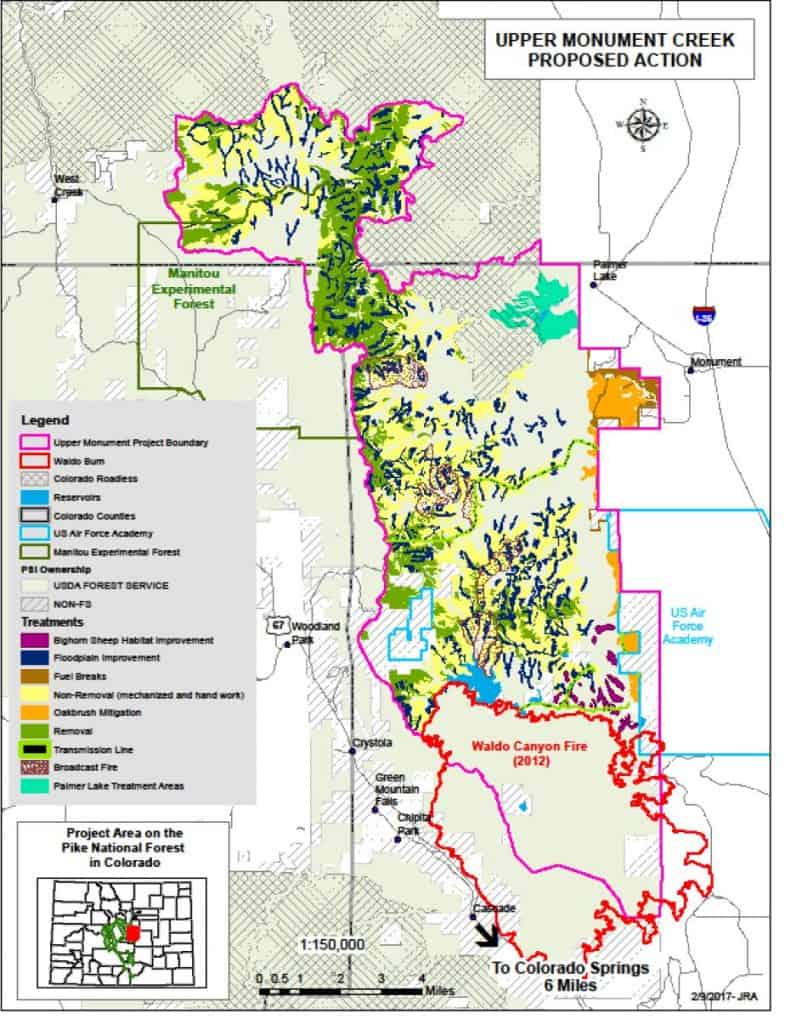

The take-home message is that forests are trying landscape-scale NEPA. We’ve heard from many scientists and others that we need to “increase the pace and scale of treatments to get fire back on the landscape.” So different sets of folks are trying that. People who don’t like CEs(categorical exclusions) should love these, one would think, because that’s exactly where projects and their interactions analyzed through space and time with a full EIS and all the appurtenances. In the somewhat, similar Black Hills Resilient Landscape Project, they added a multiparty monitoring effort so that findings toward the beginning could inform projects toward the end- that sounds great to me. Theoretically, this could be the perfect form of NEPA for ongoing vegetation management and prescribed burning programs.

This WaPo story is interesting for many reasons, and worthy of our attention because it reflects the intersection of concerns about how NEPA is done nd about doing land management actions. The story kind of shifts between the idea of “doing NEPA” and “whether treatments work” and “whether you can afford them.” I look at “doing big NEPA” as setting the NEPA table. You don’t know if the chef (Congress (not the President), the WO and your region) is going to give you one french fry, or a five-course gourmet meal with wine. You don’t know if the State or TNC or other partners will pop into the kitchen and fix a nice dessert. Now, if you are the chef, would you want to serve a dining room where tables were set or not?

The 15-year project, a marked departure from the agency’s historical approach to restoration, is moving forward as President Trump blames the deadliest wildfire in California’s history on “gross mismanagement of the forests” — a widely disputed allegation.

(It seems to be a WaPo standard along with the ever-present Democracy Dies in Darkness banner, that each story must somehow involve the narrative that Trump is bad. Of course, Trump’s statement might have been a reason to look into this topic for them, so maybe his tweets are having some positive benefits! My italics.)

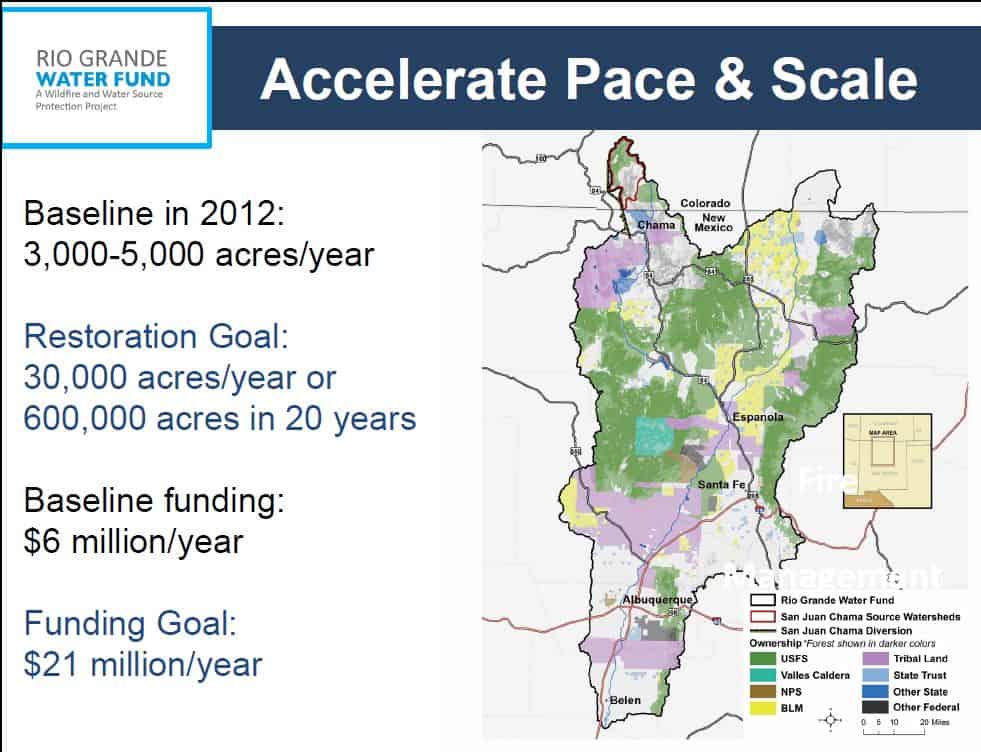

The Trump administration’s shift to decades-long management plans encompassing vast stretches is in stark contrast to the Forest Service’s historical practice of grooming parcels of 3,000 to 10,000 acres over a period of months. In New Mexico, the agency is preparing an environmental report for the 185,586-acre Luna Restoration Project in the Gila National Forest. Work on the 179,054-acre La Garita Hills Restoration Project in Colorado’s Rio Grande National Forest is underway.

NEPA folks have been talking about “big gulp” project for many years. One concern was strategic.. bigger projects make bigger targets for folks who want to litigate them. In planning, we used to talk about the “flotilla of small boats” compared to the Queen Mary. If litigators want to be efficient with their time and energy, they would tend to go after big projects. I’m not sure if that is the reason, but many of these larger projects have been successful in areas where litigation is not so frequent. The Black Hills, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming. There’s also the Blue Mountains Resiliency Project, started in 2015 with a link here. The sweet spot might be “where infrastructure still exists and litigation is not so frequent.”

As Andy mentions in his quote, 4FRI was also large-scale and started long before Trump. During the Obama Administration, I remember calls with CEQ in which CEQ asked EPA to stand down from their concerns about a large project on the Black Hills. Their point was that no changes to CEQ regs are needed, it is possible to do large projects with existing regs. In this case, it was indeed possible with high level support and inter-agency strong-arming when necessary. My point is that the pattern of going toward landscape-scale NEPA has been going on longer than the current Administration.