Back to the roots of this blog.

- Black Hills NF revision

On November 1, USDA responded to the Request for Reconsideration from the Black Hills Forest Resource Association pursuant to the Data Quality Act regarding the assessment of timber harvest on the Black Hills National Forest. It found “no compelling evidence to support your request to retract (withdraw) GTR-422,” while directing the Forest Service to release an addendum addressing some issues. The Report indicates that current harvest levels are too high. (The article includes links to the response and the Report. We discussed the agency’s original response here.)

On November 29, the governors of South Dakota and Wyoming sent a letter to the Forest Service criticizing the GTR and asking the Forest Service to produce another assessment for the forest plan revision process that avoids relying on the GTR. This article includes a link to the letter.

- Blue Mountains socioeconomic report

On another side of this coin, an editorial in northeast Oregon has praised the release (in October) of the “Blues Intergovernmental Council Final Socioeconomic Report.”

This new socioeconomic report is important because it gives officials who will craft another Blue Mountains Forest Plan the kind of data that is specific to our region. To create a plan of any kind, the right kind of information is necessary. Now, federal officials will be able to draw from information that is more comprehensive and detailed.

(Of course, some might reply that providing more information is a waste of time because it won’t actually influence the decision.) The Report may be found here:

- Nantahala-Pisgah NF revision

The Carolina Public Press has run another series on the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest. This one delves into the how and why of their planning for old growth. In short, according to the forest supervisor, “We’re trying to find a way to get this issue out of the limelight every time we propose a project.” I also found these perspectives interesting:

Although old-growth is currently underrepresented in Pisgah and Nantahala, Forest Service “natural range variation” models suggest old-growth should be roughly 50% of the forest, and the Forest Service expects that over time, forests currently not considered old-growth, will age into that category.

According to the agency, even if the stand on Brushy is considered old-growth, Brushy Mountain and other stands like it throughout the forest and within the 18,944-acre project analysis are not uncommon; 33% of land in the analysis area have forest stands 100 years or older.

“Only one-half of 1% of the forest is old-growth in the Southeast,” Williams (Chattooga Conservancy) told CPP in 2019. “That is the reason within itself to leave it alone. Cutting old-growth right now under any circumstances is foolish and irresponsible.”

In relation to that last comment, I’d also note that, while a forest plan only governs management of national forest lands, here is what is required if a viable population of wildlife species cannot be supported by a national forest (36 C.F.R. §219.9(b)(2)(ii)):

Include plan components, including standards or guidelines, to maintain or restore ecological conditions within the plan area to contribute to maintaining a viable population of the species within its range. In providing such plan components, the responsible official shall coordinate to the extent practicable with other Federal, State, Tribal, and private land managers having management authority over lands relevant to that population.

The release of a final plan is apparently imminent.

- Other forest plan revisions

Here is the most recent revision schedule posted by the Forest Service, dated May 18, 2022. It does not show any new revisions starting in 2022 or 2023. However ….

On December 14, the White River National Forest discussed their forest plan revision process. According to this article:

The exact objectives of the revised plan are still a work in progress, according to Bianchi, but broader goals have been outlined. One is to increase restoration of forest space damaged by fires, insects, disease and invasive species by prioritizing strategies like prescribed burns that can lessen the spread of wildfires and lead to healthier soil in the future.

Other goals are to allow the plan to respond to modern issues that weren’t present when it was last updated in 2002, such as the threat of the mountain pine beetle and the impacts of e-bikes. The plan’s revisions are also expected to focus on the impacts of climate change, something Bianchi said “wasn’t a big conversation in 2002.”

The revision process for the Lolo National Forest Plan will also begin this month. The Forest solicited input about public engagement through December, and highlighted new technology. A regional team is also being used. Completion is expected in 2025, and the first webinar is scheduled for January 10. (This article includes a link to the Forest website.)

- Northwest Forest Plan FACA committee

On November 18, the Forest Service published a Federal Register Notice inviting nominations (by January 17) for a Northwest Forest Plan Area Advisory Committee. While the term “revision” is conspicuously absent, the new committee’s likely use in revising plans for national forests in that area can be inferred from some of its purposes. In general,

“The purpose of the Committee is to provide advice and recommendations on landscape management approaches that promote sustainability, climate change adapations, and wildfire resilience while providing for increasing use of and demands from National Forest System lands in the Northwest Forest Plan area.”

The Committee will be asked to make recommendations in the following areas (with my links to planning highlighted):

- Planning options that complement the national Wildfire Crisis Strategy to assist the U.S. Forest Service transition to greater proactive wildfire risk reduction and related vegetation management.

- Approaches to address the dynamic nature of ecosystems, utilize adaptive management, monitoring, and integration of future uncertainty into land management planning.

- Application of the best available science regarding the following primary issues: (a) the ecological importance of mature and old growth forests; (b) climate change, fire, and associated disturbance processes; (c) terrestrial and aquatic reserved land use allocations and the relationship between the two; (d) the climatic diversity of forests encompassed by the NWFP area; and, (e) habitat connectivity at multiple scales in light of changed conditions.

- Incorporation of traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous perspectives and values into federal forest planning and management.

- Communication tools and strategies to: (a) help provide greater understanding of landscape or programmatic level planning options and requirements and (b) enhance outreach efforts, public engagement, meaningful Tribal consultation and participation, targeted outreach to underserved communities, and stakeholder collaboration within the scope of the Committee.

- Issue preliminary discrete recommendations in sequence with Forest Service NWFP planning timelines.

News articles suggest the public has made the same connection:

“The committee’s recommendations will become the basis for the first significant updates to the (plan) in nearly three decades.” (Cascade Forest Conservancy)

As to those “planning timelines:”

“The Committee is expected to need two years to carry out its objectives. All deliverables will be submitted to the Designated Federal Official (DFO) according to planning schedule needs.”

I would infer that this is viewed as pre-work for the revision process, and that there may not be much other public engagement for the next two years, but who knows? (If somebody does, please share.)

- Mountain Valley Pipeline amendments

Following litigation that stopped construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline across part of the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, the Forest Service is proposing to amend its forest plan to allow the project to cross 3.5 miles of the Jefferson National Forest. On December 23, the agency published a Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement Notice of Availability. In all, the Forest Service proposes to amend 11 standards in its plan to accommodate pipeline construction.

This article includes a link to the project website. More background on the litigation may be found here (Wild Virginia case).

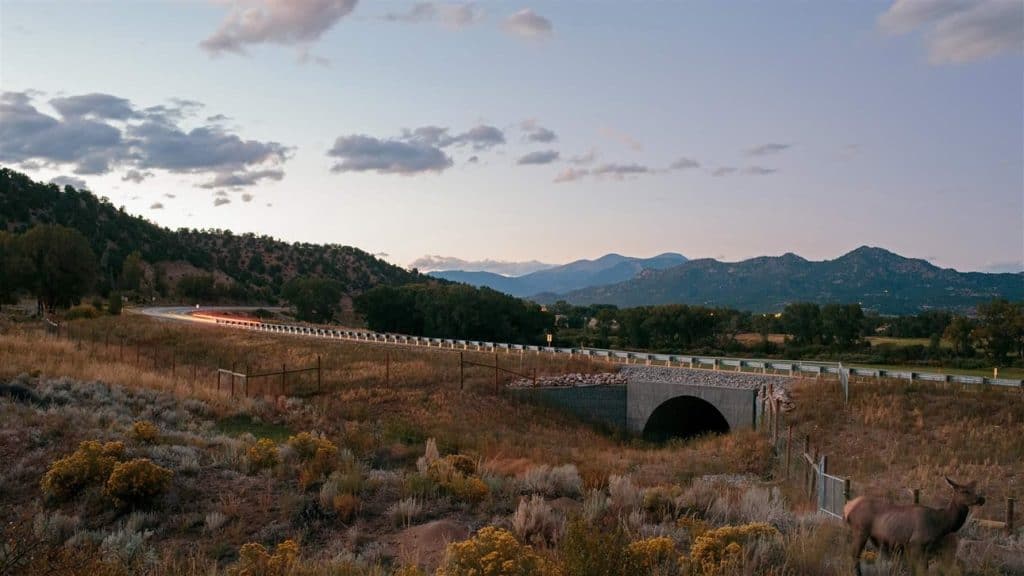

- BLM habitat connectivity

On November 15, the BLM issued a new policy “designed to protect connections between habitats for fish, wildlife, and native plants, preserving the ability of wildlife to migrate between and across seasonal habitat.” The policy, in the form of an Instructional Memorandum, calls for BLM state offices to assess areas of habitat connectivity and conduct planning, on-the-ground management actions, and conservation and restoration efforts to ensure those areas remain intact and healthy, and able to support diverse wildlife and plant populations. The BLM Press Release includes a link to the policy.

- BLM solar energy

Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland announced on December 5, 2022, that the Bureau of Land Management will develop an updated Solar Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (PEIS) to help guide solar energy development on public lands throughout the West. The proposed updated PEIS will replace the existing Western Solar Plan, developed in 2012. That Solar Plan for six southwestern states categorized land according to its suitability for solar infrastructure by establishing solar energy zones, which were areas of land prioritized for development; areas of land that should be excluded from development; and variance areas, or areas of land that were neither excluded nor prioritized. The update is necessary because of “technology advances, new resource information, and shifts in energy market economics.” It may include the five northwestern states and incorporate two other regional plans in California and Arizona. This article includes a link to the press release.