Yesterday I posted this asking the question, why 15% of the total backlog $ to the Forest Service? But let’s not lose track that everyone worked together to achieve this, and it made its way through an otherwise divided Congress by amassing support through the work of a coalition and politicians of various stripes doing their legislative thing. So you would think that this would be a time to celebrate! And it is.. and I think the cosponsors in the Senate, Gardner and Manchin, especially deserve to be congratulated.

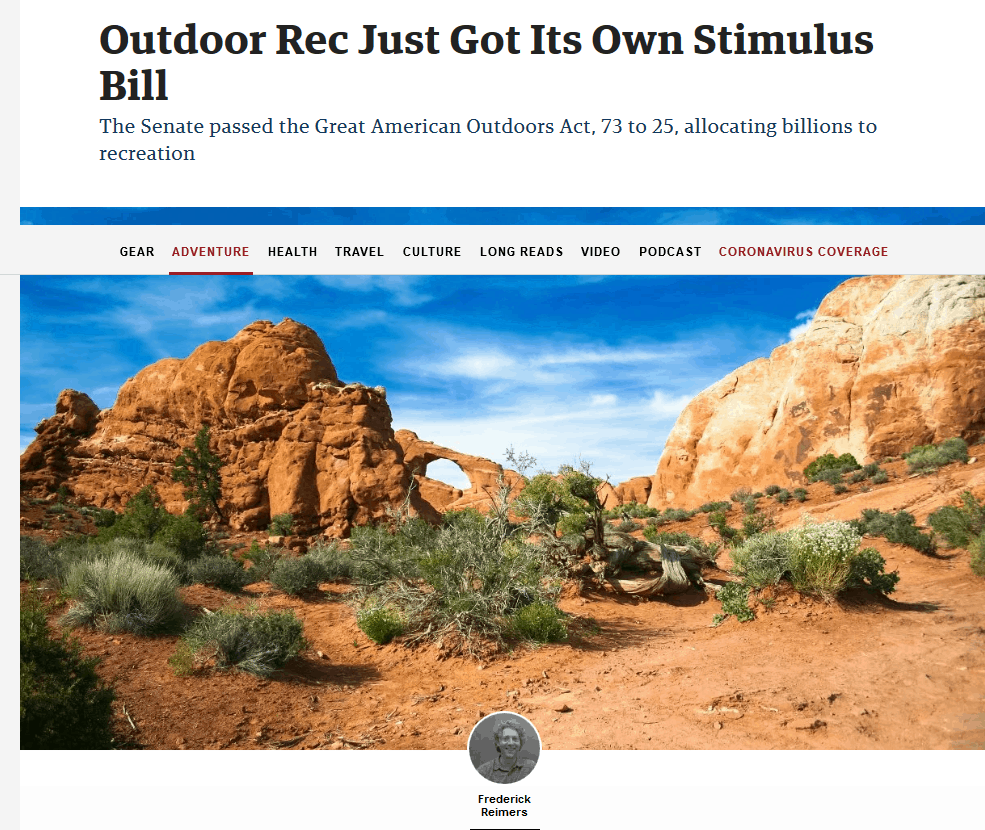

My favorite story was this one from Outsider Magazine by Frederick Reimers.. I think he got both the celebration for all of us, and the responsibility of Senator Gardner right.

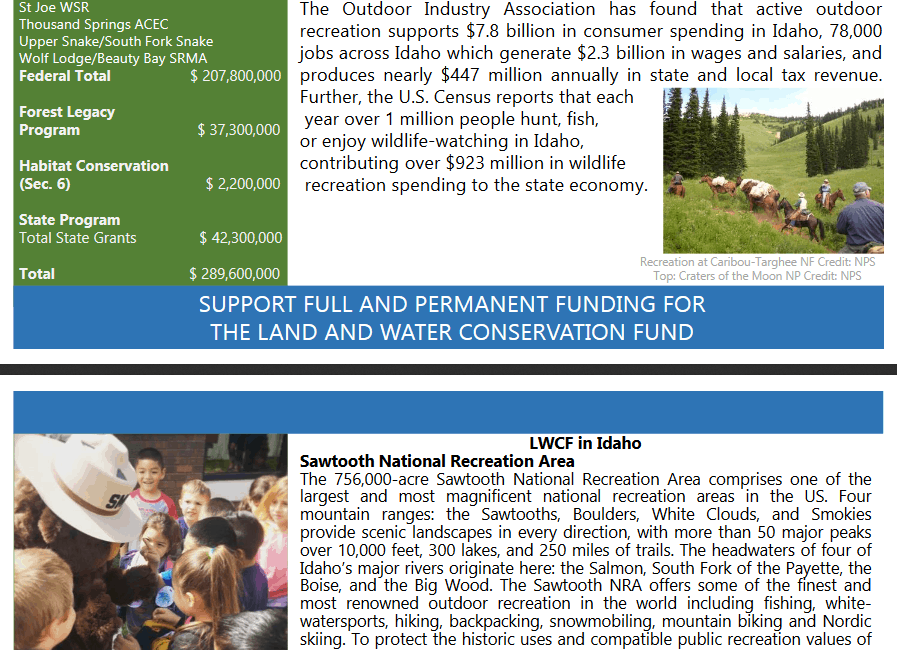

Earlier today the Senate passed the Great American Outdoors Act, allocating billions to support outdoor recreation in two separate ways. The first is by providing $9.5 billion over the next five years to help the National Park Service and other federal land-management agencies address their maintenance backlogs. Federal public lands are suffering from $20 billion in deferred maintenance costs, with $12 billion of that accumulated by the National Park Service. The second is to mandate that the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), widely considered the nation’s single best funding tool for outdoor recreation, be permanently financed to its maximum allotment of $900 million annually. In March the president called for such a bill to land on his desk.

It’s a remarkable breakthrough at a time when the White House has been hostile to federal conservation and land-management agencies and to the LWCF; Trump’s proposed 2021 budget slashed the Park Service budget by $587 million and allocated just $15 million to the LWCF, a mere 1.6 percent of its allotment. The bill passed by a vote of 73 to 25. Proponents, including the bill’s sponsor, Republican Cory Gardner of Colorado, tout the Great American Outdoors Act as a way to get people back to work after millions have been laid off in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. “Years of bipartisan work have led to this moment and this historic opportunity for conservation,” says Gardner. “Today the Senate passed not only the single greatest conservation achievement in generations but also a lifeline to mountain towns and recreation communities hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic.”

(Sharon’s note: Colorado is full of “mountain towns and recreation communities.”)

A bipartisan group of lawmakers introduced their version of the legislation in the House of Representatives on June 4, and passage of that version is expected in the coming weeks, clearing the way for the president to sign the bill into law.

“We are going to have to rebuild the economy, and this can be a really big part of that,” says Democratic senator Martin Heinrich of New Mexico, noting that nationally, outdoor recreation contributes $778 billion in consumer spending and supports 5.2 million jobs, yet “our trails and campgrounds aren’t in the shape that they should be, which directly impacts economic activity on public lands and in gateway communities.”

In May, more than 850 signatories representing conservation organizations, local governments, and state and regional tourism boards urged congressional leaders to support the bill. “The Great American Outdoors Act will ensure a future for nature to thrive, kids to play, and hunters and anglers to enjoy,” they wrote.

Senator Heinrich of New Mexico, in addition to Gardner and Manchin, appears to be a special hero to Forest Service fans:

Heinrich lauds Republican senators Lamar Alexander of Tennessee and Rob Portman of Ohio, in addition to Gardner and Daines, with being tireless champions of the Great American Outdoors Act, which he says was named “to appeal to the White House.”

Heinrich, who most observers credit with driving the effort to expand maintenance funding beyond the Park Service, explains that while the Bureau of Indian Education doesn’t have a recreation mission, it was included in the bill because, by “historical accident,” the agency was placed in the Department of the Interior, and therefore, he says, “time and again their funding levels get left out. Sometimes you have to deal with the history that puts us where we are.”

Disappointingly, IMHO, the Paonia, Colorado-based High Country News reprinted a piece from the HuffPost that focused on the “vulnerable” Republicans and implied that they only supported the bill because they are “vulnerable.” It was part of an effort called Climate Desk, although the link between the GAOA and climate is less than direct IMHO. I recognize that partisan politics is one lens to view the news. It shouldn’t be the only lens, though, even if it’s easier to acquire that reporting from NGO-funded news sources.

“It is a desperate attempt to convince their constituents that they aren’t working on behalf of corporations and that they care about what the American people care about,” said Jayson O’Neill, director of public lands watchdog group Western Values Project.

We discussed the Western Values Project in this post, which also has a link to Dave Skinner’s writing in the Flathead Beacon, and an E&E News story.

I hope every state has an outlet like Colorado Politics. It helps us understand who is funding whom to what end, always of interest.

Based on CoPo stories, the Sierra Club has taken a particular dislike to Senator Gardner, from this CoPo piece from November.

“The organization notes that Gardner has introduced a bill to reauthorize of the Land and Water Conservation Fund, but his heart isn’t really in it. “[H]is apparent goal is not to pass full funding for LWCF, but rather to maximize the number of positive press hits he gets talking about full funding of LWCF,” according to the Sierra Club. “He has put forth an amendment he knows will not get a vote and in reality does little to move the ball forward.”

Given the outcome with the Great American Outdoors Act, that statement seems remarkably non-prescient. Or this one from CoPo in December:

“Sen. Gardner sits in the majority in the Senate, sees himself as a leader in his party, so there is no good reason for him not to get full funding completed by the end of this year,” said Emily Gedeon, conservation program director for the Colorado Sierra Club. “He puts himself out as an ardent conservationist, but talk is not enough, and he needs to be calling on Senate leadership to get this done.”

After rolling out five critical billboards around the state — including along the main road to the incumbent Republican’s hometown, Yuma — the environmental advocacy organization announced Tuesday that it has another $150,000 in TV ads on network stations in Colorado Springs, Denver and on the Eastern Plains to run through Dec. 20.

I understand that the Sierra Club must think that a D majority in the Senate would be a good thing for the environment, but can we all just take a deep breath and celebrate something good for a few days? And consider, for a minute, that it’s conceivable that Gardner is representing our state’s and people’s interests, and the idea that it’s a political ploy may be worth a few sentences, but is certainly not the whole story.