Thanks to the Norbeck Society for providing links to the Friday videoconference! In case you haven’t been following the different threads , here’s a link to the info, including an agenda and list of speakers. It’s open to the public via the web. It’s from 1-3 MT on Friday May 1. That’s today. Now on to Frank’s second post.

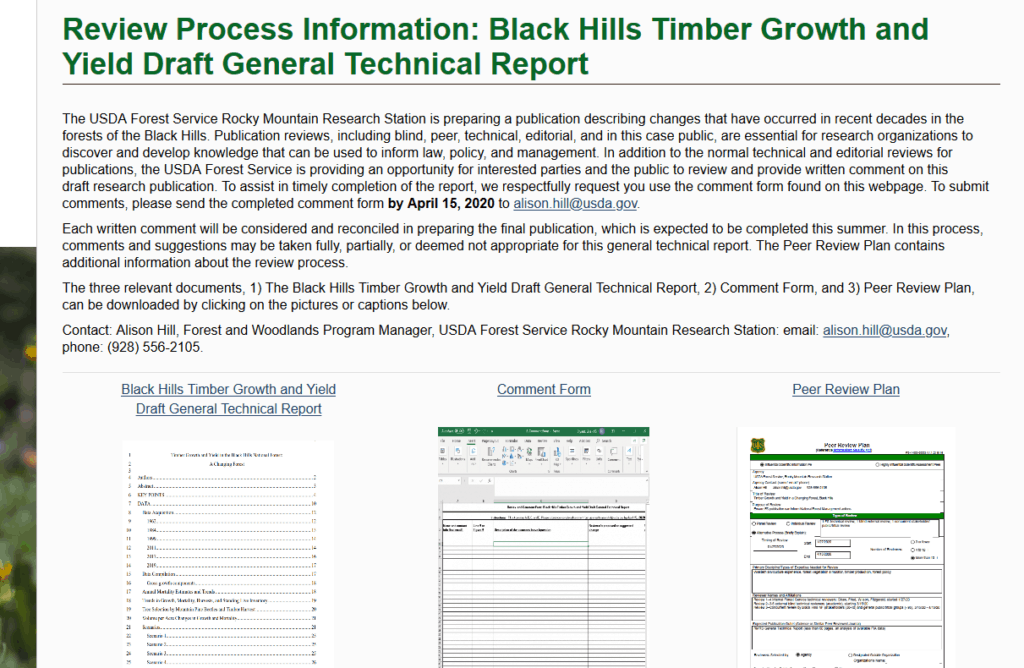

Sharon Friedman writes “One of the interesting things about this paper is the peer review process- internal, external, and stakeholders and the public….I think it’s a great idea to have a variety of perspectives. Some of the most rigorous scientific reviews I’ve seen are when people with different opinions, interests, and experiences on the ground review a paper.”

Our experience with direct engagement of interested and affected publics in forest management began in earnest in 1970 when then-Southwestern Regional Forester William “Bill” Hurst wrote a letter to all hands extolling the brave new world of public involvement in forest management. The idea of direct public involvement didn’t come to Bill in the dark of night. As in our own time, the Forest Service was working hard to remain relevant in the sea of competing public interests, Congressional distractions, and Secretary-level politics that whipsaw the agency in every Epoch from 1895 until today.

The idea was to capitalize on the reputation the Forest Service then had as what authors Clark and McCool described as a “Superstar Agency” in their seminal work, Staking Out the Terrain. Hurst and his peers reasoned that involving the public directly in decision-making would build a cadre of political support that would support Forest Service management into the future and speak for the agency in political fights down the road. After all, people trusted us. Kids wanted to be forest rangers. Lassie ruled the airwaves. Capitalize on all the good will, Hurst reasoned. History will note that Bill’s expectations were earnest in intent, naïve in conception, and not at all what he envisioned in terms of real outcomes. Inviting the public into the agency house resulted in land and resource management planning and all the many iterations of public policy and high drama we have known since 1980 when LRMP really took off and the world changed.

The idea to involve our scientists and their research in what I view as an ill-considered and potentially disastrous, open-ended “peer review” process with any and all hands commenting is a direct descendant of Bill’s effort in 1970 and driven by the same desires that somehow involving the public in our planning and management processes, and, now, in our science and data, will somehow elevate our work. As we learned in 1980 and subsequent years, our shared agency hopes that opening the document to some form of “public peer review” will build a strong political consensus for the report and its conclusions is wrong. It will not. It will, however, compromise Forest Service science in unlooked for ways that may ultimately damage both the data and the scientists. Public involvement in this paper will not change the outcome of future decisions on forest management in the Black Hills in any way.

It’s a hard lesson made harder in the knowledge that “peer review” from all hands was not an idea supported by or even considered by the authors. The principals in this case are useful pawns as various levels of the agency and outside interests attempt to legitimize the conclusions in the report. The thinking is that if enough outside interests (like the Norbeck Society, Forest Service retirees, and others) weigh in and are familiar with the report and its projections, the weight of political power will swing away from the current timber industry in favor of timber volume reductions. For a host of reasons, that will not happen.

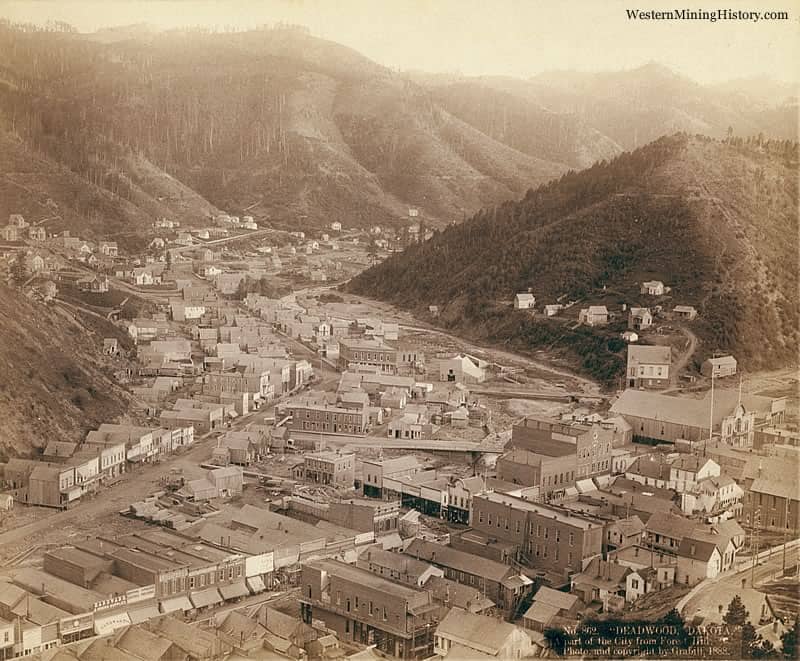

Jim Neiman’s monthly electric bill is $30,000, month in, month out, and won’t change barring any unforeseen events. The timber industry including Jack Baker and Jim Neiman support thousands of jobs and hundreds of families in two states. The combined economic clout of a robust and creative forest products industry are critical contributors to well-being in the southwest corner of South Dakota and eastern Wyoming and that industry enjoys the full support of the President, the Secretary of Agriculture, the Chief of the Forest Service, the Regional Forester, Senator Thune, Senator Rounds, Congressman Dusty Johnson, and every community leader who counts across two states.

In addition, the industry has operated in an unbroken cycle of success since at least 1885 providing timber and other forest products for the Hills and beyond. They have continued to do so up to and including this year. When there are blips in production, those blips are products of market conditions, not Forest Service actions with the glaring exception of 2000 when agency machinations gone wrong resulted in zero timber offered or sold. The combined experience of leadership at all levels has been that the timber industry can and does take care of itself using a combination of market forces, entrepreneurial skill and creativity, tenacity, and dedication to sustainable forestry over time.

The report paints a picture that is contrary to our combined experience in Black Hills forestry. The message is not trusted and there is no agreement on potential outcomes or conclusions. In such a situation the status quo will rule the day absent any surety that is should not.

The Forest Service must be highly circumspect in inviting public participation in scientific analyses and agency management, especially when the likelihood is high that public expectations for change from some quarters will not be met. In this case, the status quo will rule coming decisions related to ASQ and that’s OK. The problem is actually self-regulating. Either the timber industry is right and they will continue to use their skill, creativity, and market forces to make a living and provide forest management, or they will fail to do so, also because of market forces quite apart from Forest Service aspirational objectives. Please take heed, RMRS…you may think inviting “peer review” today looks good, but wait until they are editing your text and bar graphs to fit with their personal perspectives…your political scientific reports will frustrate you more than you can know.

In my opinion, the correct focus of the agency should be to compile data, provide analysis of current management and alternatives to it, and work to merge competing interests to the best of their ability. The Forest Service has no business trying to strong-arm the timber industry. A sketchy “peer review” of data and analysis is not helpful.

Additionally, the rise of the use of “unplanned fire in the right place at the right time” and “reintroducing wildfire to fire-deficit ecosystems,” or “forest management by applied wildfire,” has endangered the agency’s moral high ground to try to limit or control proven, traditional, systematic, forest management programs like the sale of federal timber. The timber sale program is a controlled disturbance agent well understood by most foresters. No one knows what the outcome of applied wildfire will be through time. I merely point this out to inform the complexity of the discussion. There is a high level of distrust in Forest Service forest management exacerbated by various attempts to (inappropriately) involve the public, on the one hand, and exclude the public on the other (there has been no public process to disclose the cumulative effects of management by wildfire or “managed fire” as it is called today).

Frank Carroll is managing partner of Professional Forest Management, LLC, PFMc, a full service forestry and grassland consultancy. Frank and partner Van Elsbernd have been working since 2012 to understand and help shape wildland fire policy. Frank is the principal author of the wildfire impact analysis for the Mount Rushmore Independence Day Environmental Assessment. PFMc has helped over 600 clients recover almost $600 million in damages from wildfires across the West. www.wildfirepros.com [email protected]