Alan Rogers/AP

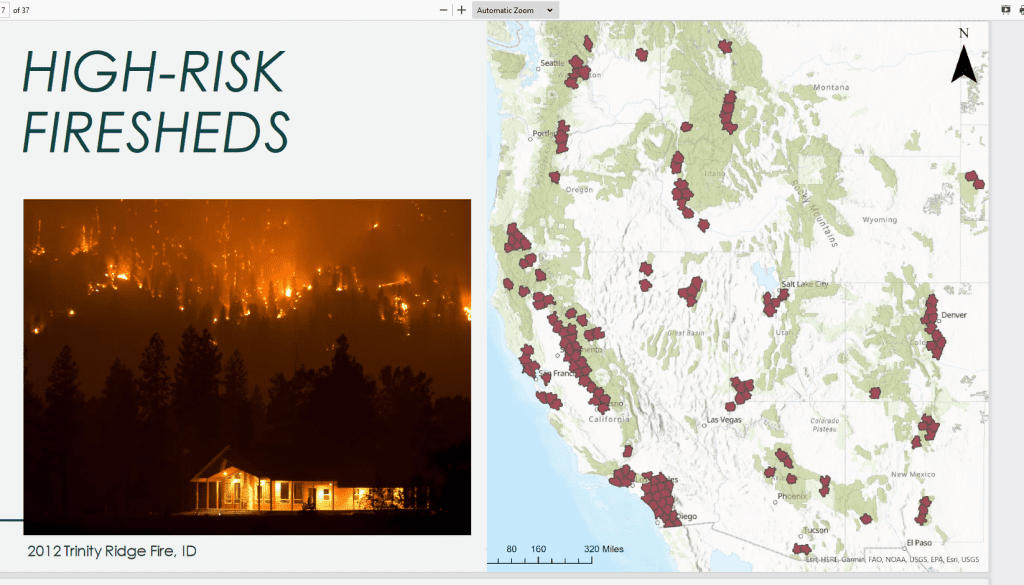

I’m always interested in parallels between the forest products industry and the oil and gas industry, which are so different and yet.. so enemized by some (of the same) folks. Here’s a case where according to some politicians, O&G is bad if they drill (we’ve been hearing about that for years) but now we are told that they are equally bad for … not drilling, as political winds and international events have shifted. It doesn’t seem altogether rational. In my FS career, I found that when people aren’t logical.. there’s usually politics involved. Of course, I’m sitting here on computer (powered by coal and natural gas), heated by propane, hoping for a snowplow (no electrical ones yet available) to run by.. The transition to low carbon energy will be at least ten years, and also adaptation may well call for the increased of fossil fuels, say in fire suppression- airplanes, trucks and so on.

Are we planning to demonize the oil and gas industry from now until then? Because that seems like not a good use of our time and emotional energy, let alone the impacts on my neighbors and colleagues producing energy for which I, for one, am grateful. Perhaps it’s easier to vilify industries if you don’t know the folks involved in producing it. Real people doing real things that we really use every day. I think you can be for appropriate regulation without the good guy/bad guy rhetoric. I think there’s something else at work here, in this kind of industry-hate, but I don’t know what.

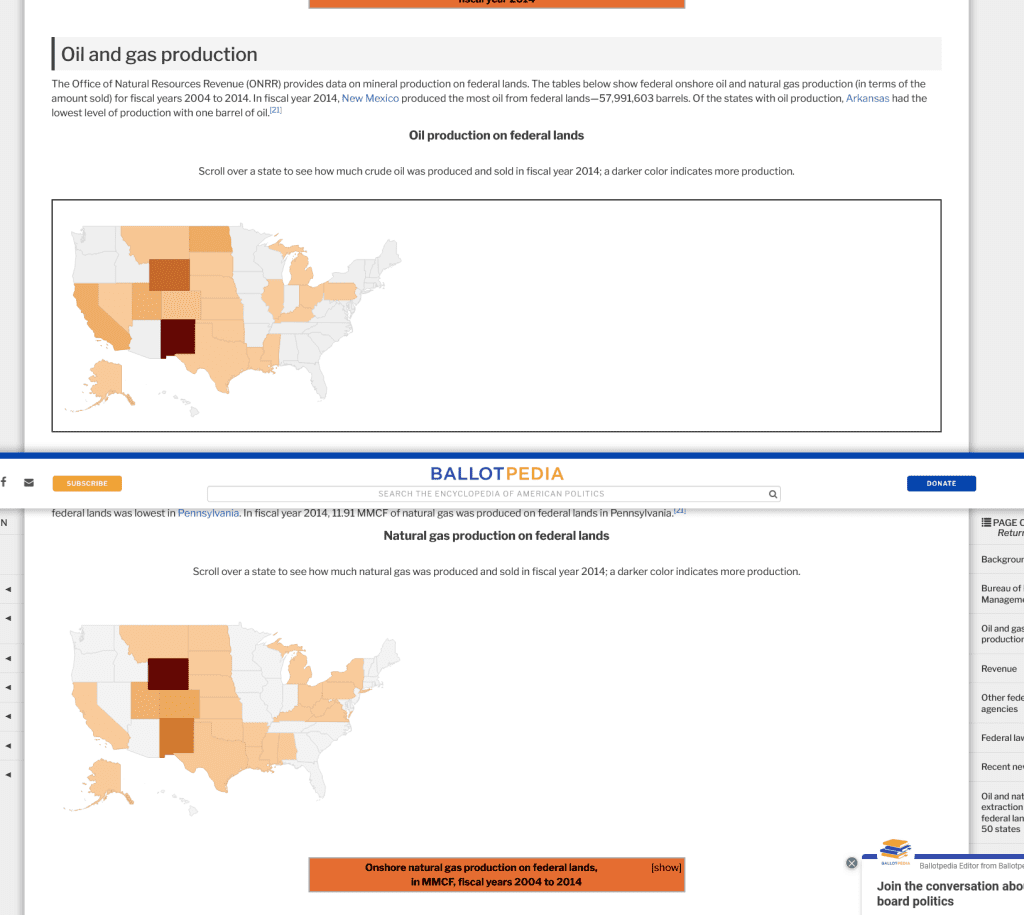

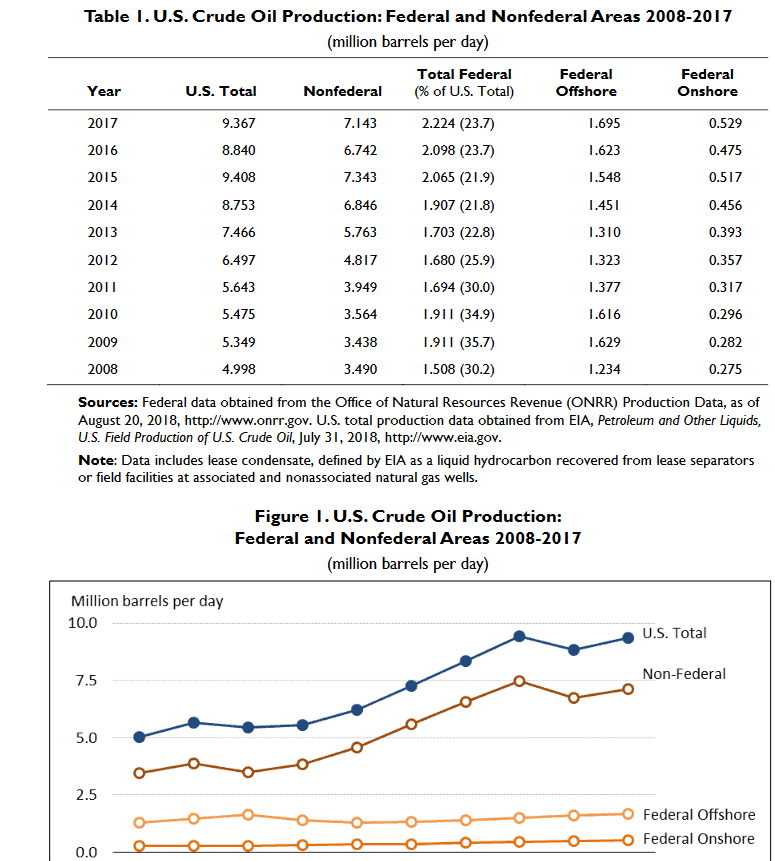

Anyway, I think E&E News had a good article on “fact-checking five claims in the Russian energy debate”. As far as I can tell it’s open for non-subscribers. Here’s what the reporters pieced together. The Admin is apparently approving APD’s but not leasing. Perhaps one of our legal friends can help us understand the difference between onshore and offshore litigation here. Based on this story.. onshore leasing litigation led to court-induced stoppage, but the courts also struck down a freeze on offshore leasing. Does offshore use a different social cost of GHG? Or wasn’t there an offshore lawsuit on that? Somewhat puzzling to observers.

When it comes to onshore leasing, a decision last month from a federal judge blocking the administration’s use of the social cost of greenhouse gas emissions has resulted in further delays for Biden’s planned auctions.

While the administration has continued to approve permits to drill new oil wells, it has yet to conduct onshore auctions for new leases, which are normally held four times a year across multiple states (Climatewire, Feb. 22).

But some industry advocates have dismissed the Interior Department’s excuses regarding climate litigation. They recall that candidate Biden ran on a plan to ban oil on federal lands.

And even though the courts have ruled against a leasing moratorium, Western Energy Alliance President Kathleen Sgamma argued a ban remains “in effect because no leases have been offered for sale. Period.”

Only recently has the president reversed course and urged oil companies to drill after he banned imports from Russia (Greenwire, March 9).

When it comes to offshore leasing, a judge last year struck down the early Biden freeze, and the Gulf’s largest offshore lease sale was held in November.

But conservation groups sued, and a judge for the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia vacated the sale. The administration opted not to appeal the decision. The fate of an additional Gulf sale scheduled for later this year is unclear.

Industry advocates lamented the disruption of future oil and gas on those leases, which would have lasted for at least 10 years.

More broadly, industry players expressed concern the administration does not appear on track to release a lease schedule when the current one expires in June.

“Uncertainty around the future of the U.S. federal offshore leasing program may only strengthen the geopolitical influence of higher emitting — and adversarial — nations, such as Russia,” said Erik Milito, president of National Ocean Industries Association.

The U.S. hasn’t had an offshore lease sale since November 2020, but experts said general uncertainties about future plans are likely causing more trepidation.

“I don’t think you can just discount it,” Book said of Biden’s early signaling to industry on drilling. “It’s part of the story and it depends from company to company and project to project. But being told, ‘No more leasing’ is not nothing. It doesn’t mean that it stops production tomorrow, but it may discourage investment for years to come.”

And while the Biden administration approved more oil and gas permits on public lands in his first year than President Trump, in recent months the increase has tapered off (Energywire, March 14).

I could easily see a rush to get your APD approved.. if you think it’s only a matter of time until the Admin figures out a legal way to slow or stop those as well. And..below is a big issue for those who follow NGO’s like the Center for Western Priorities..

In response to Republican attacks on the leasing ban, Biden and other Democrats note that oil and gas companies already hold thousands of approved permits on federal lands.

“They have 9,000 permits to drill now,” Biden said last week. “They could be drilling right now, yesterday, last week, last year.”

That number is correct, with the Bureau of Land Management reporting 9,173 onshore permits available to drill at the end of last year. But industry sources and observers said there are myriad reasons why a given company might not drill a permit right away — including that it might not have much oil.

White House press secretary Jen Psaki has also suggested reporters should be asking executives why they are sitting on their hands.

“Do you think the oil companies don’t have enough money to drill on the places that have been preapproved?” she asked.

The industry rejects that line of argument as a red herring, and experts generally said the White House is oversimplifying. Drilling programs are dictated by the rise and fall of the price of oil but also the amount of free cash to drill and investor support for that spending.

Companies with footprints in different oil and gas regions are weighing all their drilling opportunities against each other, for the best place to expend capital at any given time.

That said, experts expect drilling to pick up following a post-pandemic lag caused by companies shifting cash back to investors rather than in new projects.

Book also noted that companies are already going through their inventories of “drilled but uncompleted” wells, or DUCs, which have been drilled but not yet fracked.

“It’s not like not using a permit is a business strategy. If they’ve decided not to use a permit, it probably reflects conditions economically and to some degree their expectations for what they think the market future looks like,” Book said. “There’s a little latency built into this, but right about now I’d expect to see some more permits being used.”