With apologies to those of you not interested in the Planning Quagmire..

With apologies to those of you not interested in the Planning Quagmire..

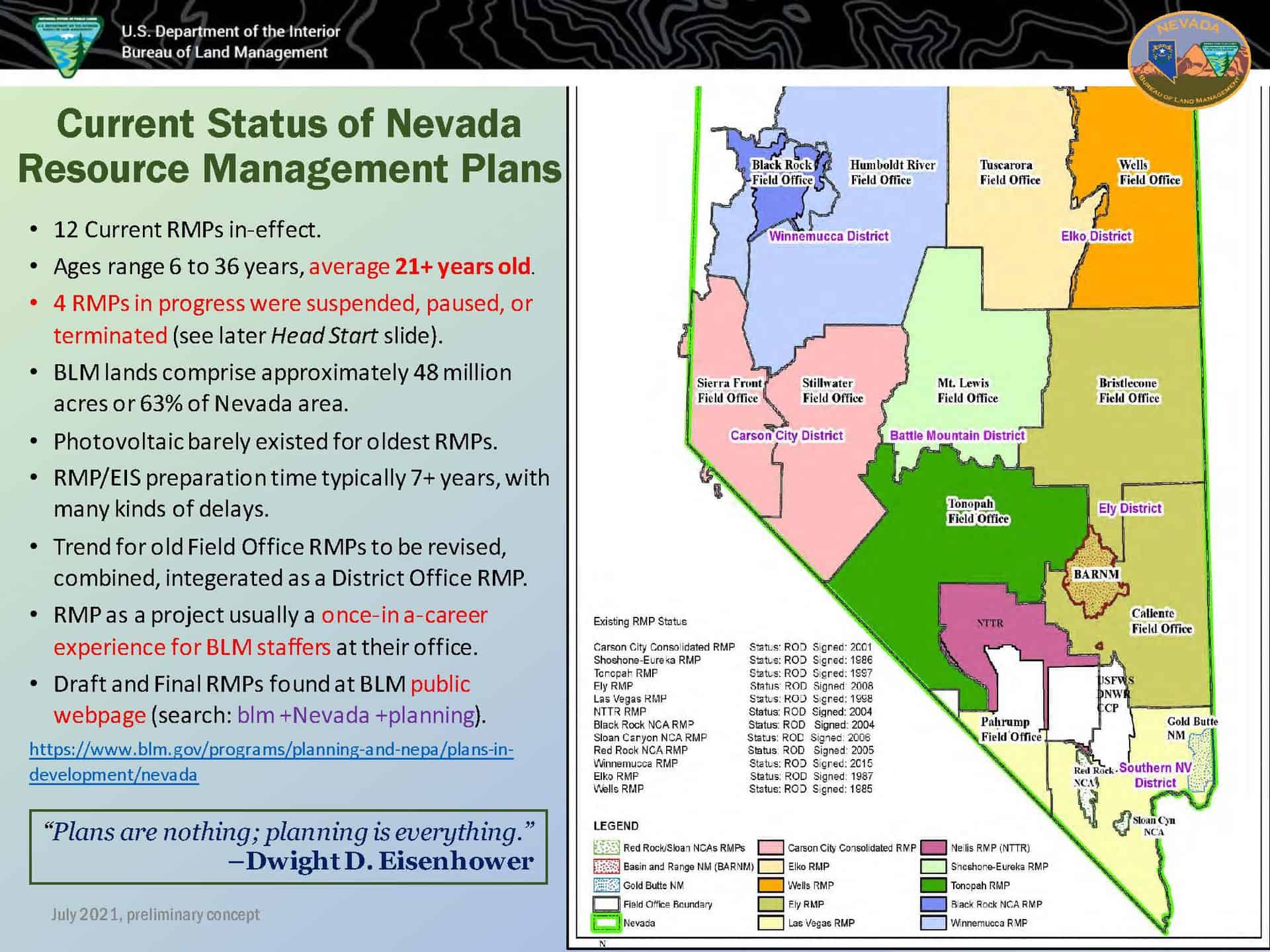

Susan Jane Brown in this comment “is it really a NFMA problem, or is this a multiple use problem?” So the answer would be to look at another multiple use agency (in this case, FLPMA and BLM) and see if they have problems finishing their plans. My experience was that our State Office was more intent on finishing (more sticks in the bundle? sharper sticks?) than our Regional Office was, but that varied by FS personnel. We even had a joint plan for a while (RMP and Plan Revision) on the San Juan. The San Juan worked very hard on it, with a great deal of creativity, but as I recall someone stuck a fork in it.. can’t remember exactly why. Anyway, I found this interesting powerpoint from last summer by BLM Nevada. Here’s one slide.

Advantages of a Single RMP Revision

Efficiency of scale to meet timeline goal for completion by October 2025.

Implements recent Executive Orders and meets Department of Interior Priorities.

Brings half the current RMPs into the 21s t Century –including Elko and Battle Mountain Districts, which are still living in the ’80s– while resolving RMPs that no longer address current issues.

Avoids continuations of serial, piecemeal RMP amendments, such as for Winnemucca District Visual Resource Management and Southern Nevada District land disposals.

Assures consistency throughout Nevada for criteria, such as leasing or permit stipulations.

Harmonizes with concurrent planning to start by Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, covering 5.6 million acres of mountain ranges in Nevada surrounded by BLM lands.

Incorporates existing, disjointed RMP Amendments into a single plan, including the widespread Greater Sage-Grouse Plan Amendment of 2015, which functions like a separate planning overlay.

Integrates latest standards for geospatial and corporate data, accessible through a map-based public website that can be continuously updated as a “living document” encapsulating future amendments.

Reduces risk and adds specificity to RMP conformance statements that may be based upon overly broad and outdated criteria in older RMPs.

Satisfies long pent-up demand for updated, revised RMPs. Finally gets it done.

Potential Disadvantages & Risks of a Single RMP Revision

o Legal challenges may drag the whole RMP/EIS, although risk reduced with multiple RoDs.

o Funding continuity less certain for sequential Fiscal Year allocations.

o Workload heavy for Nevada State Office and increases for District Offices.

o Whole efforts seems too formidable for ambitious timeline, thus requiring a firm Project Manager.

o Implementation-level decisions would not fit into the RMP and would have to be separate

Here’s another slide:

Meeting Department of the Interior priorities RMP to implement recent Interior Priorities, encapsulating multiple use with sustained yield per FLPMA goals.

Tentative slogan: Planning is cool again to tackle the climate crisis…. (nod to Executive Order 14008, 27 Jan. 2021) Identifying steps to accelerate responsible development of renewable energy on public lands and waters.

No BLM State has more solar applications pending. RMP to feature Designated Leasing Areas (DLAs) and/or Project Development focal areas, new or confirmed transmission corridors, recognition of ongoing projects already initiated.

Energy Act of 2020: RMP supports national goal of 25 GW additional renewable energy generation nationwide by 2025.

Integrate with State of Nevada initiatives (e.g., Renewable Portfolio Standard, 2020 State Climate Strategy).

Strengthening the government-to-government relationship with sovereign Tribal nations.

Early, targeted outreach for public and tribal engagement through RMP envisioning or pre scoping.

Tribes invited to be Cooperating Agencies as a supplement to formal Consultation.

Requests from Tribes represented within the RMP range of Alternatives.

Making investments to support the goal of creating millions of family-supporting and union jobs.

Objectives and specific projects, including infrastructure, identified for on-the-ground actions and business opportunities.

Projects may be carried out by Climate Conservation Corps, AmeriCorps, non-profits organizations, and/or private firms, especially for activities or actions identified as Implementation Strategies a few months after RMP completion.

Working to conserve at least 30% each of our lands and waters by the year 2030. (America the Beautiful or 30 x 30 Initiative)

Planning designations for conservation and climate goals, such as via Areas of Critical Environmental Concern (ACECs),

Backcountry Conservation Areas (BCAs), Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) areas, Wilderness Character (LWC) units, etc.

Land use designations, including mitigation sites, serve as an Administrative method for conservation, thus informing any subsequent, more durable conservation via Executive Action or Federal Legislation. See Wilderness Society example.

Centering equity and environmental justice.

Appropriate, close scale to identify Environmental Justice communities with latest census and other population data.

Targeted outreach conducted, with public meetings brought to EJ communities in rural and urban areas.

It almost sounds as if the RMPs also do a variety of things at different scales.. picking where solar should go and what land should be “protected” prior to Executive Action or legislation for “durable” conservation. That seems like an extremely useful exercise, but identifying “specific projects” might be at a different scale. Nevertheless, we can tell from the slide pack that “getting plans done” has also been a challenge to the BLM, which fits in with SJB’s idea. And/or perhaps both NFMA and FLPMA need another look?

And with target dates for renewable installations being urgent, it seems like the BLM might have its own “climate emergency (fast action) meets land management planning (slow action)” challenge. (not that they don’t have fire issues as well.)