From Emily Dohlansky (many thanks!):

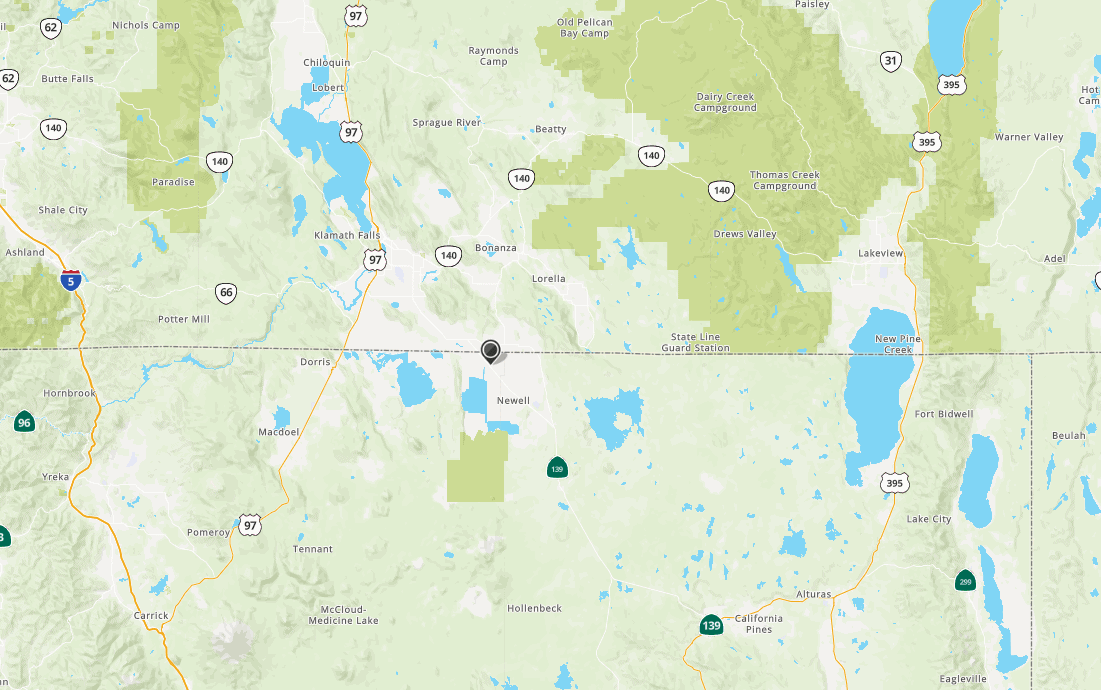

“The Sacramento Bee recently published a five-part series on Northeastern California that challenges the concept of “wild” places in the state. I found all of the articles fascinating and well-balanced. The one on wild horses garnered a lot of negative feedback from advocates, and wild horse management isn’t something that I see mentioned here often. I thought it would be interesting to have a discussion about the articles, their shortcomings, and a path forward in this “post-wild” world.”

I think each one is interesting enough to deserve a separate post, so let’s start with the first one:

WE’RE NOT GOING BACK TO THE STATE OF NATURE’

State and federal regulators and scientists, meanwhile, are largely paralyzed to do anything about any of it, thanks to a constantly growing array of regulatory demands that suck up their budgets and staff time. There is very little innovation in the public’s lands and wildlife management these days.The threat of lawsuits from the competing interest groups makes restoring even a few acres of habitat a years-long process of expensive studies, planning and lawyering. Deviate one inch from a “management plan” that’s already been hashed out in the courts, the agency will almost certainly get sued again, or some politician loyal to a faction will come in and pass a law or change a rule to make the agency’s job even harder.

And the places I love are worse for it.

To try to save some of what’s left of these habitats, it will require a clear-eyed look at how we think about, fund and manage our lands and wildlife. It also will need to come with an acknowledgment from those living in major cities that these places aren’t truly “wild,” and they haven’t been for more than a century.

“We can’t just walk away,” former California Gov. Jerry Brown told me. “We’re not going back to the state of nature, but we should try to advance environmental goals, and at the same time we have to respect people, their livelihoods and their traditions. It’s a messy process.”

At their heart, these stories are about how the land-use decisions of the past have collided with divisive partisan politics, lack of funding, inattention and bureaucratic paralysis to create crises that are only going to get worse for both the ecosystems and the impoverished rural towns that make up my favorite corner of the state.