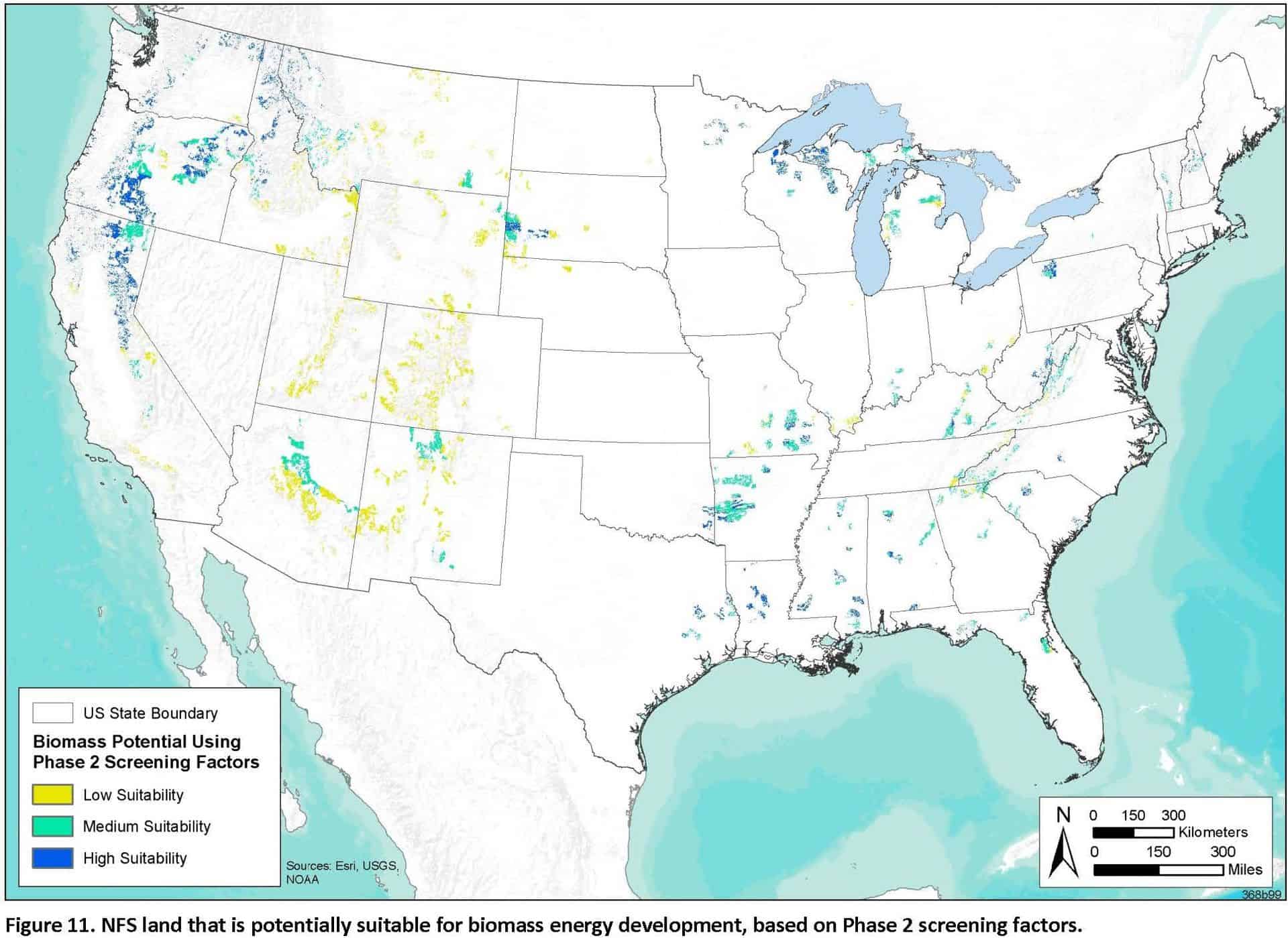

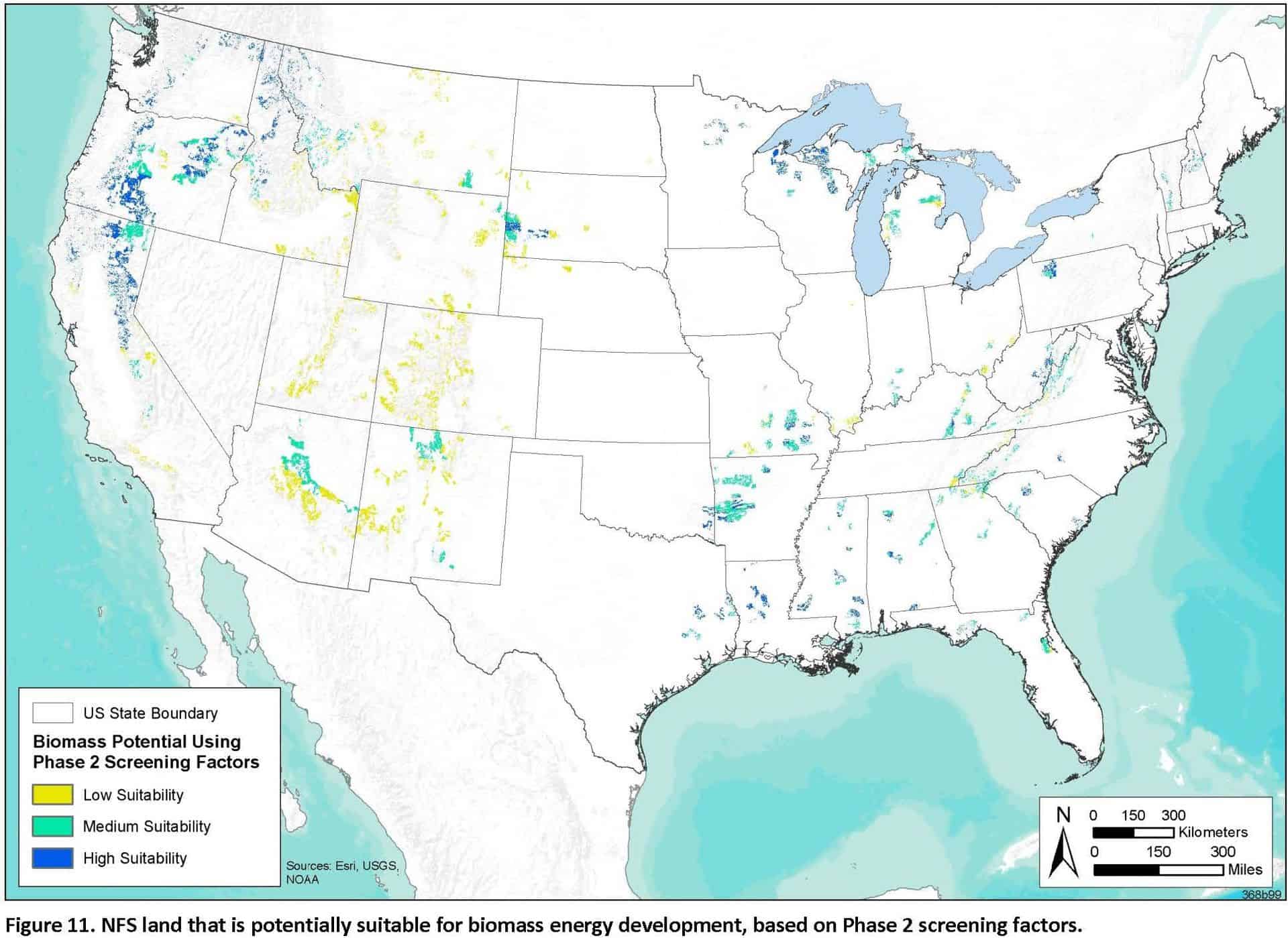

From the 2013 Argonne National Lab study

From the 2013 Argonne National Lab study

Apologies to everyone and especially Mac.. I couldn’t get the links and image to work on some platforms for this so am trying various tricks, like reposting the whole thing. Thanks to folks helping me troubleshoot the problem! Please comment below if you can’t see the one link to the Argonne report nor the chart.

Here’s Mac McConnell’s idea for the new Administration:

MANAGING NATIONAL FORESTS FOR CLIMATE CHANGE MITIGATION

In 2011 the United States Forest Service (USFS) promulgated a program document entitled Strategic Energy Framework.

“The Forest Service Strategic Energy Framework sets direction and proactive goals for the Agency to significantly and sustainably contribute toward resolving U.S. energy resource challenges, by fostering sustainable management and use of forest and grassland energy resources.”

I write this paper in hopes of furthering these goals, focusing on the national forests’ signature resource: biomass.

Biomass

In 2013, the Argonne National Laboratory, under contract with the USFS, published a report “Analysis of Renewable Energy Potential on U.S. National Forest Land”. It revealed that, at that time, some 14 million acres of national forest (NF) land were highly suitable for biomass production. This resource is renewable, immense, and virtually untapped.

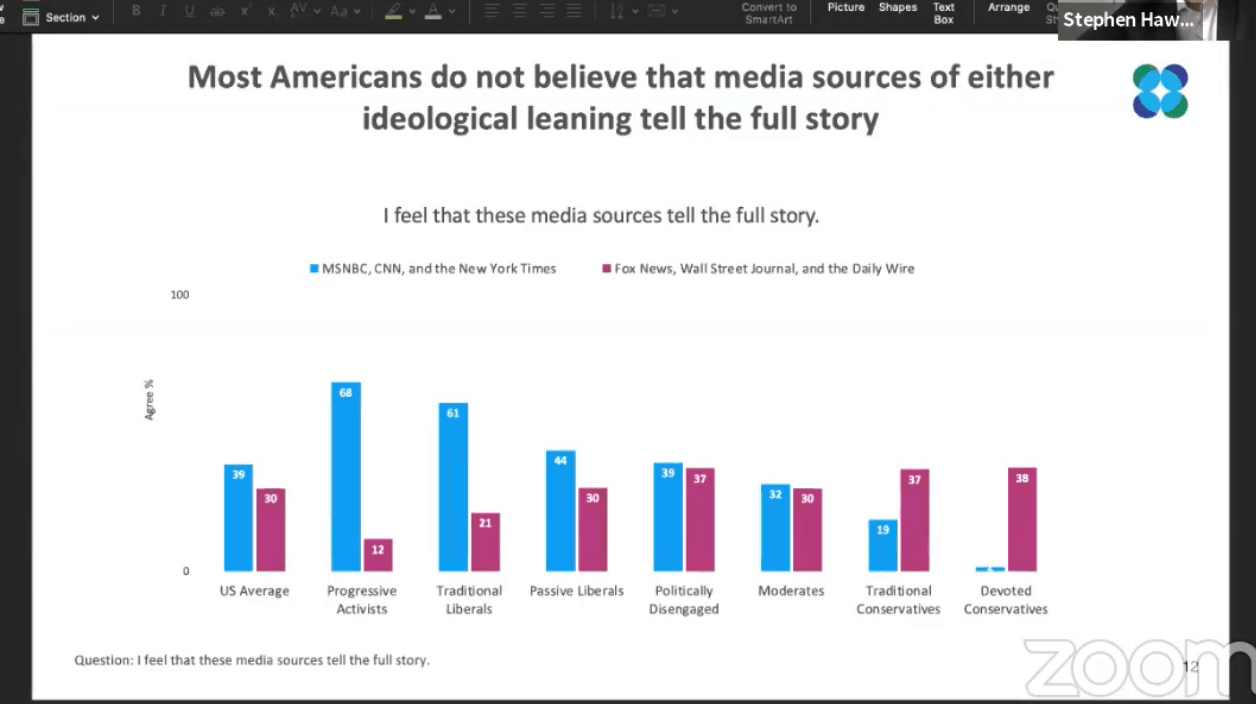

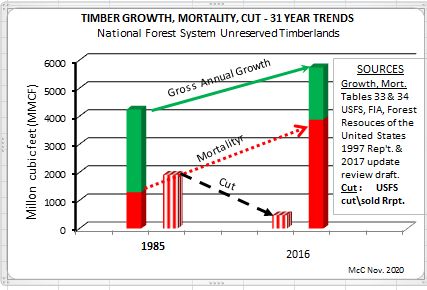

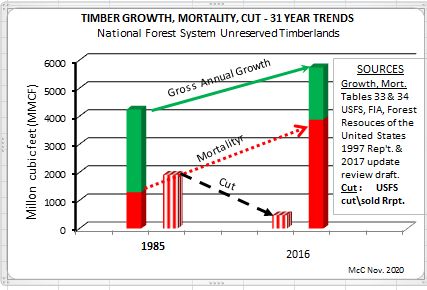

Should this resource be developed? The question has been raised as to whether the national forests can support a larger timber harvest. Alternatively, should the carbon remain sequestered in standing trees , thus slowing the progression of climate change? The answers can be found in the chart.

During the 31 years period ending in 2016, drastic changes took place in the management of national forest resources. Emphasis (dollars|) shifted from tangibles, such as timber, forage, and road construction and maintenance to intangibles (wilderness experience, endangered species and old growth protection) and fire management.

As a result of these factors, plus chronic under-funding, serial litigation, and over-planning and analysis, timber harvest has declined by 75% and the forests are now harvesting about 8% of their growth. Mortality due to fire, insects, and disease increased by 200%.. Net annual growth (Gross annual growth minus Mortality) decreased by 39%.

The chart makes apparent the long-term adverse impacts of virtual non-management. As trees in unmanaged forests and under stress from climate changes die in increasing numbers they no longer sequester carbon, but rather become sources of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide and methane. Prudent harvesting for energy biomass uses these dead and dying and unwanted trees to replace fossil fuels while creating a healthier and more resilient timber stand. It also creates a market for presently unmerchantable material and a new job market in rural areas urgently needing economic help.

Other renewable resources

While this paper focuses on biomass, the 2013 Argonne Lab report also investigated the presence of the solar and wind energy potential on NF land.

National forest solar resources are abundant with 565,000 acres of NF land with a production capacity of 56,000 Megawatts potentially available, primarily in the Southwest.

While minor wind opportunities exist locally, the principle developable areas are located on the 17 national grasslands totally 4 million acres.

Proposed Action

I propose that the Forest Service initiate a greatly expanded program of biomass utilization focused on active participation in the development of small-scale (< 20 MW) energy projects on selected national forests. This would include assistance in siting (providing suitable land for facilities), planning, financing (grants or low-interest loans), and long-term contracts that would ensure a continuous fuel supply.

Congressional authorization and funding will allow this action to take place.

Bibliography

USDA Forest Service 1997, FIA Forest Resources of the United States, 1997 (Tables 33 & 34)

USDA Forest Service 2011, Strategic Energy Framework

USDA Forest Service 2017, FIA, Forest Resources of the United States, 2017 (Tables 33 & 34)

USDA Forest Service, Annual Cut and Sold Report

McConnell, W.V. (Mac). 2018. Integrated Renewable Energy from National Forests in193 Million Acres, 32 Essays on the Future of the Agency, Steve Wilent editor, Society of American Foresters,651:333-338

Zvolanek, E.; Kuiper, J.; Carr, A. & Hlava, K. Analysis of Renewable Energy Potential on U. S. National Forest Lands, report, December 13, 2013; Argonne, Illinois..

W.V. (Mac) McConnell is a self-styled visionary who, b(uilding on his 30 year career with the U,S. Forest Service and mellowed by 47 post retirement years in the real world, hopes to change the way the Service manages the peoples’ forests. He specializes in energy biomass management (short-rotation-intensive culture energy crop systems)

*Additional Note from Sharon: The Argonne study also looked at hydropower and geothermal; it’s interesting to look at the tables by forest and also the maps for concentrated solar, PV, wind, hydro and geothermal. The biomass estimates focused on logging residues and thinning. Criteria are listed on page 12 of the report.*