This post isn’t meant to serve as a be-all and end-all piece about all wildfires in general. Rather, it’s more specifically about the current Oregon wildfires burning in clearcut, heavily logged, and roaded areas of the Oregon Cascades. While these images and videos certainly don’t tell the entire story, they do tell part of the story—and a very important part of the story, I’d argue. I plan on adding to this post as time permits, so please keep that in mind.

As many of us know, different ecosystems burn differently. High severity fires are natural, normal and expected in some ecosystems, not so much in others. It’s important to remember that many of the largest and most destructive wildfires in recent years—in terms of human lives and structures lost—were not even “forest” fires at all, but rather more urban fires that raced through neighborhoods and communities surrounded by dry grass, brush, shrubs, and chaparral. Many of these fires also had little to do with federal public lands. However, all of these deadly fires have been pushed by heavy winds during a period of prolonged drought and record high temperatures.

The horrific Almeda fire, which started on September 8 during very high winds and blasted through Talent and Phoenix, Oregon, burning down 2,357 residential structures, had zero to do with forests and public lands, for example. Here’s what a Talent, Oregon evacuee, and scientist, Dr. Dominick DellaSala, wrote in the aftermath of that tragic wildfire.

The wildfires highlighted below all burned primarily within “stand-replacing fire regimes,” which means they are forests that typically—and naturally—experience infrequent, but severe fires. When fires in “stand-replacing fire regimes” take off and expand exponentially, they are always weather-driven—fierce winds, high temperatures and very low humidity. Let’s take a look at some of the landscapes that have burned in the Oregon Cascades since Labor Day weekend.

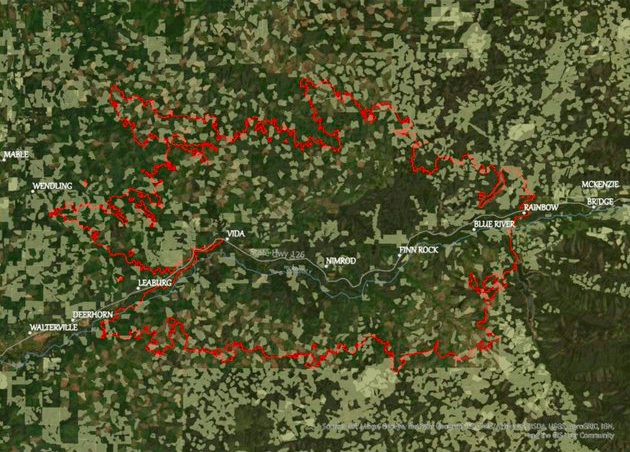

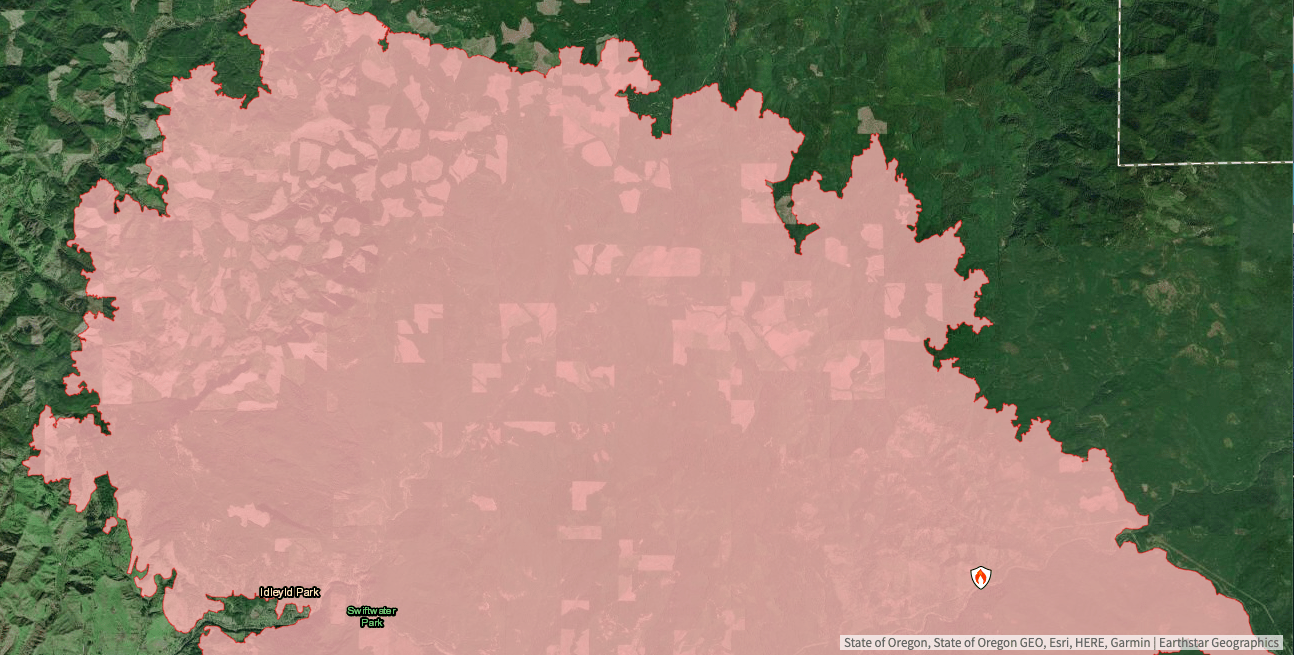

The image above is of the 170,000 acre Holiday Farm Fire, which started on the evening of September 7 during raging winds. I got the image from Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics & Ecology. The current fire perimeter is in red and as you can clearly see the fire has burned through an extremely heavily clearcut and logged part of the Oregon Cascades.

While the cause of this wildfire is currently under investigation, the Oregonian reported on September 17 that “residents told the Oregonian/OregonLive that the blaze was preceded by a power outage, a loud explosion and a shower of blue sparks from an electric line near milepost 47 on Oregon 126 – the exact location where state officials have pinpointed the start of the fire.”

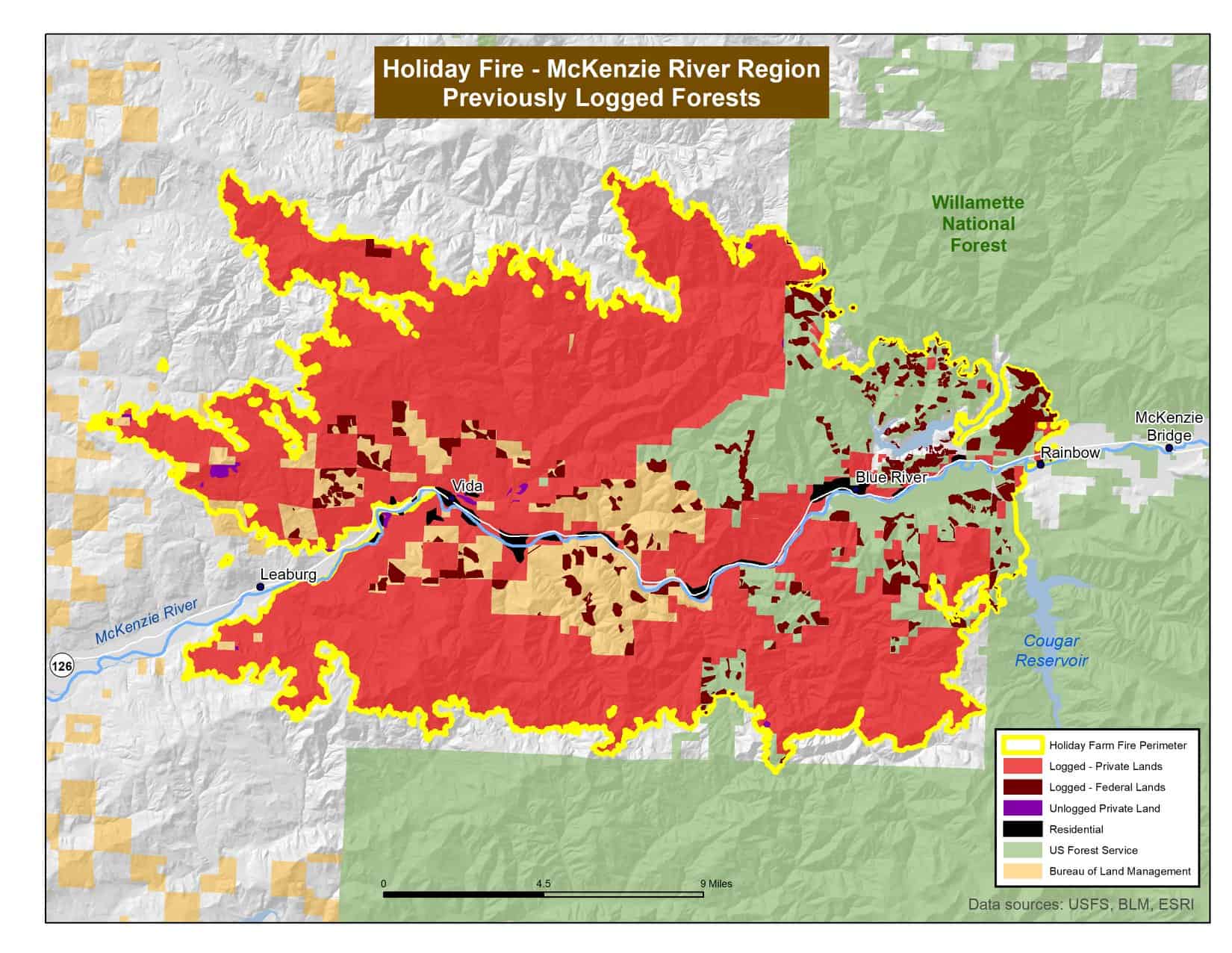

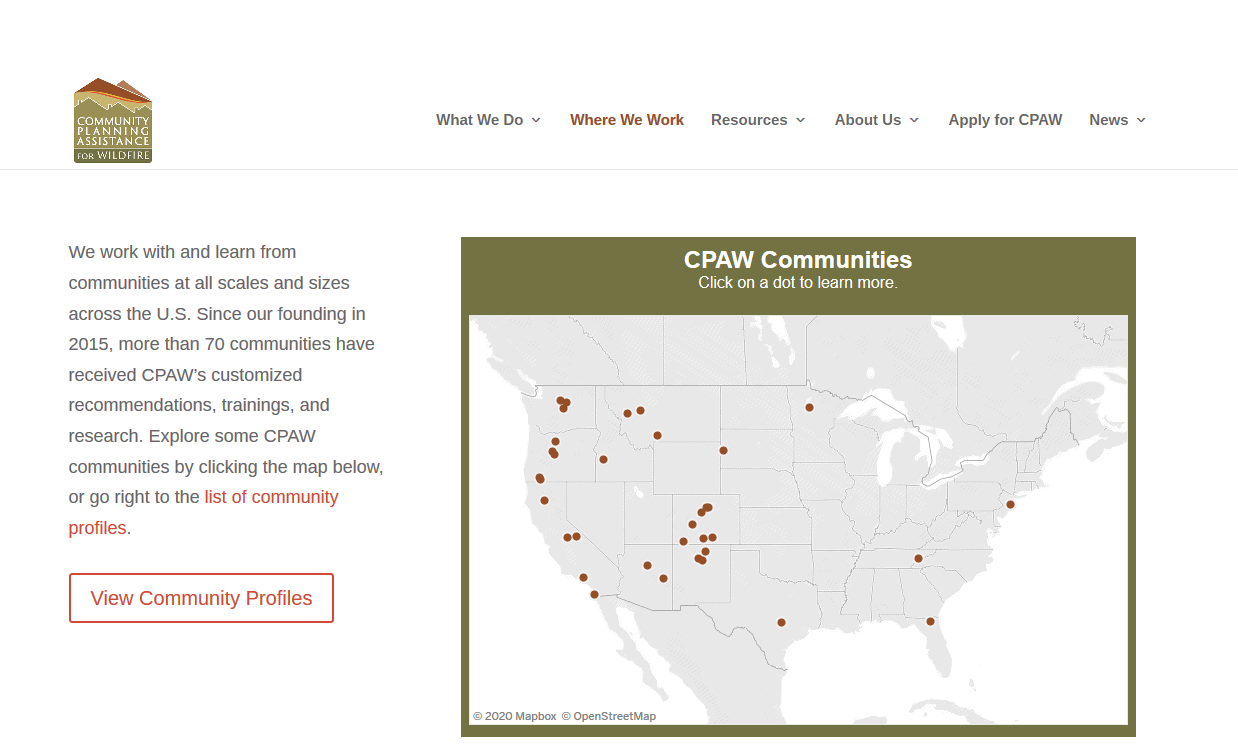

According to Oregon Wild “A whopping 76% of the Holiday Farm Fire area was previously logged” (See: shades of red on the map below).

Speaking of the southwest part of the Holiday Farm Fire. Kevin Matthews flew over what is now the south edge of this fire on July 24, six weeks before the wildfire. Matthews is a former Lane County Commissioner candidate. Below is his video.

Moving further south, above is an image of the Archie Creek Fire burning northeast of Roseburg.

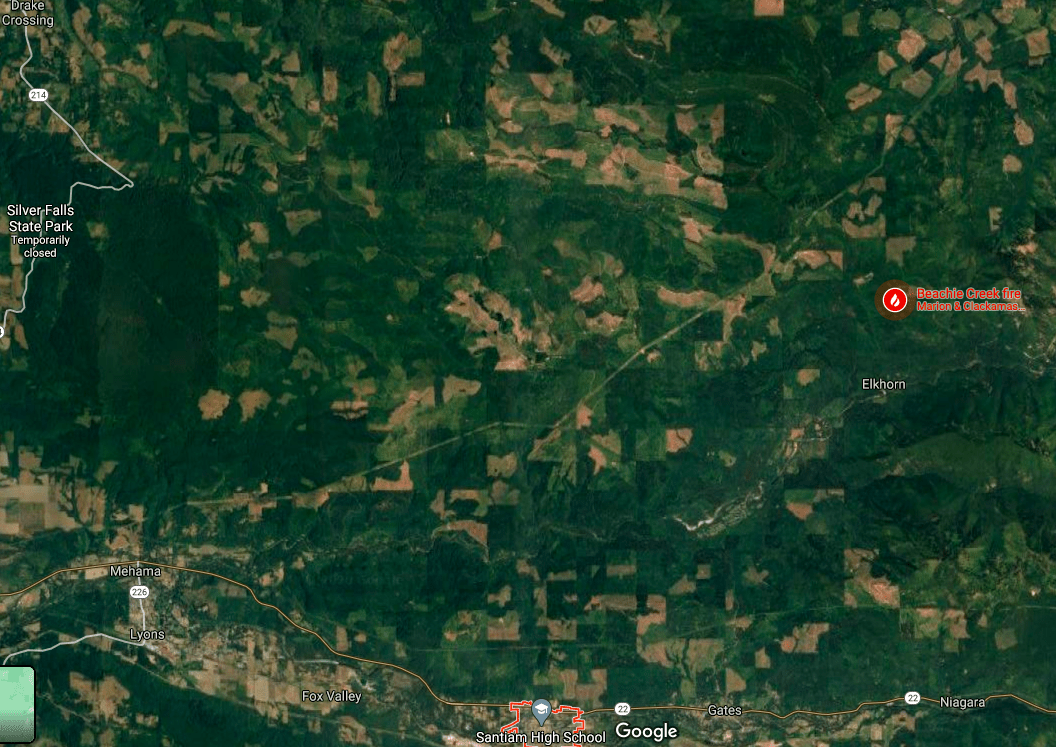

Above is an image of the Beachie Creek Fire directly north of Mill City. Fire officials confirmed that at least 13 of the fires that fed this blaze during the high wind event on Monday were caused directly by downed power lines. These fires spread very quickly fanned by what is essentially the Oregon Cascade’s equivalent of the So Cal’s Santa Ana winds or the Bay area’s Diablo winds, all of which have caused considerable damage and huge wildfire runs.

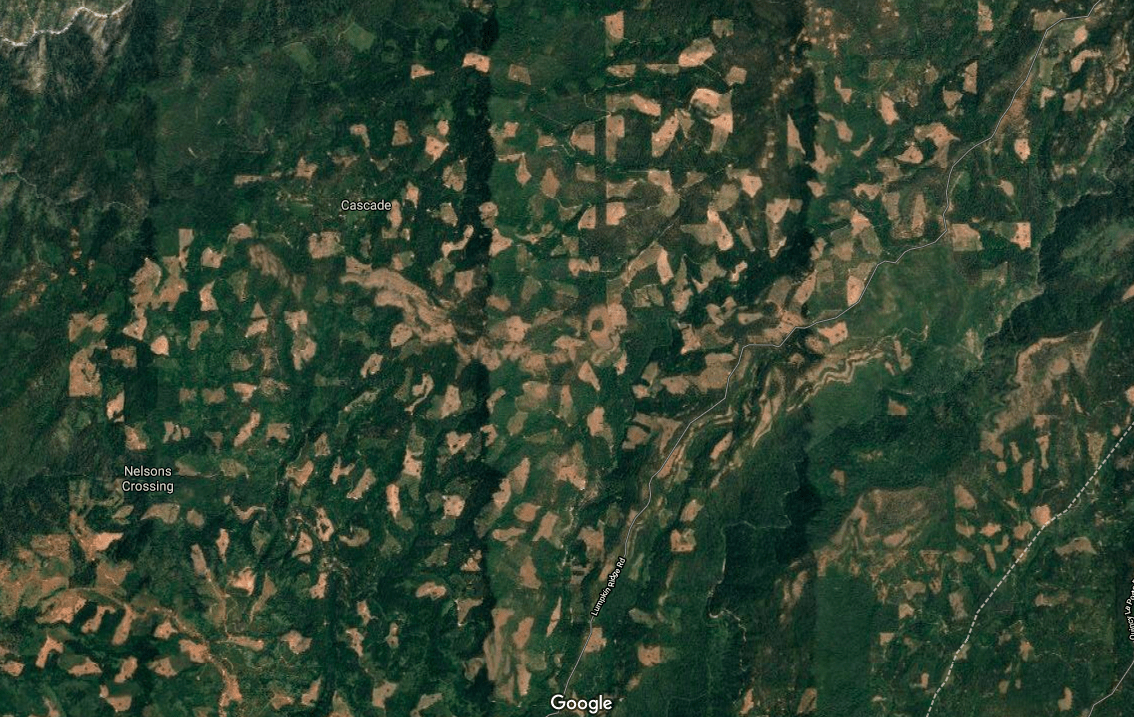

Directly above is the same general image of the Beachie Creek Fire area north of Mill City, but without the wildfire overlay so you can more clearly see how heavily logged and roaded this area is. The rest of the country may not realize it, but the Santiam River watershed and the McKenzie River watershed where the Holiday Farm Fire ripped through, as some of the most heavily logged landscapes in Oregon, which is one of the most heavily logged states in the country.

UPDATE 10/1/2020: A class action lawsuit filed against Pacific Power alleges the utility’s failure to shut down its power lines amid a historically dangerous storm caused wildfires that devastated the Santiam Canyon on Labor Day evening.

“Despite being warned of extremely critical fire conditions, Defendants left their powerlines energized,” the lawsuit says. “Defendants’ energized powerlines ignited massive, deadly and destructive fires that raced down the canyons, igniting and destroying homes, businesses and schools. These fires burned over hundreds of thousands of acres, destroyed thousands of structures, killed people and upended countless lives.” Read the full story here.

All of the wildfires highlighted above, including the Riverside Fire, burned within “stand-replacing fire regimes” within the west (i.e. “wet”) side of the Cascades. These are NOT “open, parklike stands of ponderosa pine” that may have historically burned more frequently and generally at low to moderate severity (and even at high severity when conditions were right (like maybe during a megadrought, record high temps and heavy winds…sound familiar?).

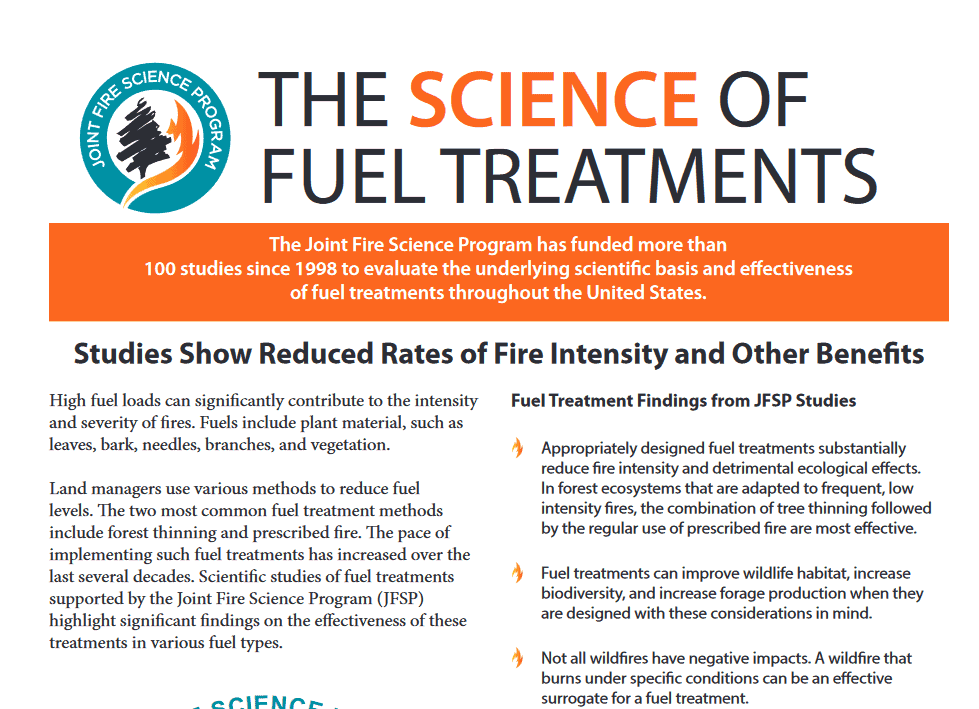

What does current science say about the forests within these “stand-replacing fire regimes” and potential “management options?” Here’s a 2018 “Innovative Viewpoint” by some of the top minds in the country on this topic:

ABSTRACT: Building resilience to natural disturbances is a key to managing forests for adaptation to climate change. To date, most climate adaptation guidance has focused on recommendations for frequent‐fire forests, leaving few published guidelines for forests that naturally experience infrequent, stand‐replacing wildfires. Because most such forests are inherently resilient to stand‐replacing disturbances, and burn severity mosaics are largely indifferent to manipulations of stand structure (i.e., weather‐driven, rather than fuel‐driven fire regimes), we posit that pre‐fire climate adaptation options are generally fewer in these regimes relative to others. Outside of areas of high human value, stand‐scale fuel treatments commonly emphasized for other forest types would undermine many of the functions, ecosystem services, and other values for which these forests are known. For stand‐replacing disturbance regimes, we propose that (1) managed wildfire use (e.g., allowing natural fires to burn under moderate conditions) can be a useful strategy as in other forest types, but likely confers fewer benefits to long‐term forest resilience and climate adaptation, while carrying greater socio‐ecological risks; (2) reasoned fire exclusion (i.e., the suppression component of a managed wildfire program) can be an appropriate strategy to maintain certain ecosystem conditions and services in the face of change, being more ecologically justifiable in long‐interval fire regimes and producing fewer of the negative consequences than in frequent‐fire regimes; (3) low‐risk pre‐disturbance adaptation options are few, but the most promising approaches emphasize fundamental conservation biology principles to create a safe operating space for the system to respond to change (e.g., maintaining heterogeneity across scales and minimizing stressors); and (4) post‐disturbance conditions are the primary opportunity to implement adaptation strategies (such as protecting live tree legacies and testing new regeneration methods), providing crucial learning opportunities. This approach will provide greater context and understanding of these systems for ecologists and resource managers, stimulate future development of adaptation strategies, and illustrate why public expectations for climate adaptation in these forests will differ from those for frequent‐fire forests.

For those who aren’t familiar, “forests with stand‐replacing fire regimes” include many forests in the West Cascades region of Oregon and Washington, much of the Coast Range of Oregon and Washington, much of forested landscape within the Northern and Central Rockies, as well as the Southern Sierras, especially forests found at upper elevations in these regions.

Next, let’s move way out of the forests and into the Home Ignition Zone (HIZ). According to the National Fire Protection Association, “The concept of the Home Ignition Zone was developed by USDA Forest Service fire scientist Dr. Jack Cohen in the late 1990s, following some breakthrough experimental research into how homes ignite due to the effects of radiant heat.” The HIZ is divided into three zones. 1) Immediate zone: The home and the area 0-5’ from the furthest attached exterior point of the home; defined as a non-combustible area; 2) Intermediate zone: 5-30’ from the furthest exterior point of the home; and 3) Extended zone: 30-100 feet, out to 200 feet.

For over two decades, the forest protection community and forest activists have been imploring people to follow Dr. Jack Cohen’s research and heed his advice on how to protect homes and communities from wildfires. I’ve spoken with Dr. Cohen numerous times about his research, as he was based here in Missoula. We’ve invited him to speak at numerous public presentations and panels. I’ve worked with him and recorded his power-point presentation for community access TV channels and we’ve mailed about 100 of his of videos to libraries across the American West for free check-out. In 2003, I produced a newspaper primer featuring Dr. Cohen’s research and recommendations and paid to have them inserted in over 500,000 papers in rural communities across the West. Countless other forest protection groups and activists also educated the public about effective Home Ignition Zone defense measures over the past 20 years.

Meanwhile, for over two decades, pro-timber industry politicians have largely exclusively called for more public lands logging with less environmental oversight, less scientific analysis, fewer protections for wildfire, and no real focus on immediately around homes. Coincidently, most all of these same pro-timber industry politicians are also pro-oil and gas and pro-coal politicians. I can think of few examples of these pro-timber industry politicians, or timber mill owners and logging industry lobbyist for that matter, sharing the research of recommendations of Dr. Jack Cohen with members of the public.

However, I can think of lots of examples of these same pro-timber industry politicians blaming wildfires this year—and in every recent year I can remember since the mid-1990s—on “environmental terrorist groups,” “environmental radicals,” “fringe groups,” and “environmental extremists.”

Of course, this is not to say that there are not some good people in the “timber industry” that get it. One such person is my friend Mark Vander Meer of Bad Goat Forest Products in Missoula, someone I literally can’t say enough good things about. Not only is Mark a logger, but he’s a certified soils scientists who also runs a successful watershed consulting business. We’ve partnered with Mark and his team a number of times over the years to do bona-fide forest restoration and watershed work. For a couple of years, I raised funds to hire Mark’s crew and we all teamed up with the West End Volunteer Fire Department to create defensible space on private land around the DeBorgia, MT community through education, action, and fellowship. We followed Dr. Cohen’s Home Ignition Zone principles and focused our work around the homes of folks who were elderly or couldn’t do, or pay for, the work themselves. Here are some scenes from that work in 2006 and again in 2007. Mark is the guy in the photos who might be able to moonlight as Santa Claus at your local department store this winter.

Make sure to also read this excellent, thoughtful, and science-based perspective on the Oregon wildfires from Ben Deumling of Zena Forest Products. Thanks so much for Susan Jane Brown for sharing this piece in the comments section here. It really deserves more attention, so please check it out and share it with people you know. Here’s some of what Ben had to say:

“The question I hear over and over is did bad forest management cause the Labor Day fires? In a word: no. The data shows that a combination of strong east winds and extremely low humidity are what caused these fires. Plain and simple. 30-40 mph winds from the east blew for over 24 hours, bringing record low humidity in the single digits to the region….Short of scraping the land bare, there is no type of forest management that could have stopped these fires. Having a discussion about the type of forest management that we as Oregonians want on both our public and private forestlands is important. Good forest management can indeed help to slow less severe fires and reduce the loss from a fire when it does burn. But those conversations are moot in this particular context.”

Again, the information presented here certainly doesn’t tell the entire story, but it does tell a part of the story. Just a reminder that I will be adding to this post as time permits.

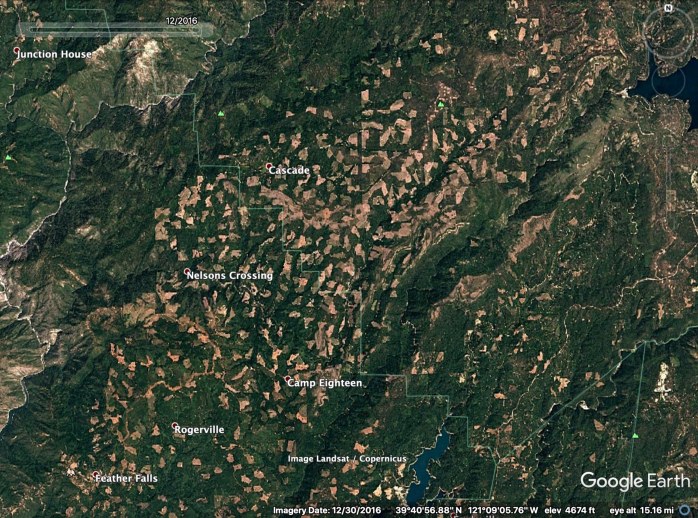

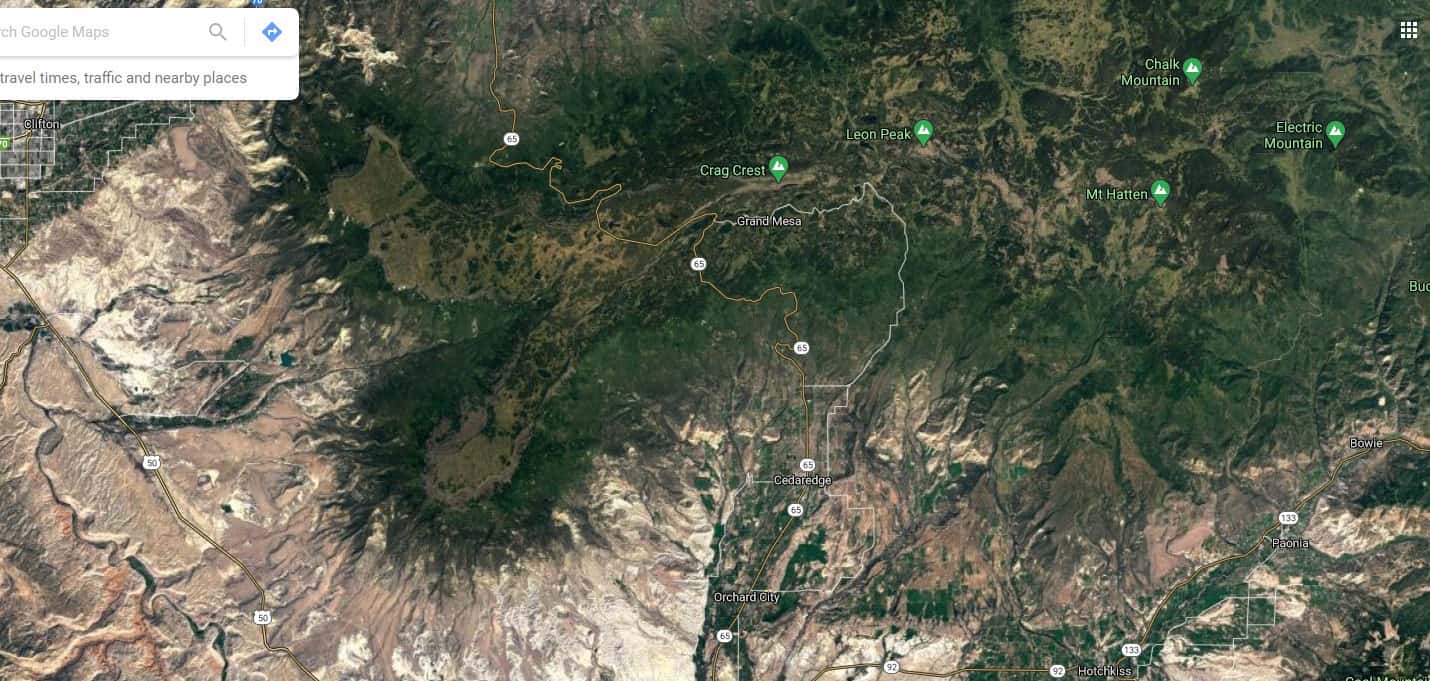

BLOGGERS BONUS: Below is a pre-fire image of the landscape where part of the 280,000 acre North Complex Fire in California has burned this year. Yes, I know this isn’t in the Oregon Cascades. By acres, it’s the 6th largest fire in state history. Maybe Trump is right and America does have a “forest management problem.” [Note: These are clearcuts…miles and miles and miles of clearcuts]

The following comment was posted by Jim Furnish, former Deputy Chief of the U.S. Forest Service on this blog

The following comment was posted by Jim Furnish, former Deputy Chief of the U.S. Forest Service on this blog