A few weeks ago, I heard Chief Moore say something like “the Forest Service is considering alternative measures for fuel reduction/wildfire resilience based on outcome not outputs.” This is somewhat related to our earlier discussion about timber targets.

I remembered that RVCC (Rural Voices for Conservation Coalition) had done some work on this, and the RVCC folks were kind enough to dig two reports up for me. So it’s worth discussing and feel free to share any other reports or thoughts in the comments. Discussions of performance measures do not normally get the blood flowing in many people I know. Retirees may just roll their eyes and say “Thank Gaia I don’t have to think about this anymore or sit in meetings or read stuff about it…” Nevertheless, here goes

It looks like there were two different thoughtful efforts. One (2020) was called “Implementing Outcome-based Performance Measures Aligned with the Forest Service’s Shared Stewardship Strategy.”

We’ll cover the other one (2022 with many of the same notable players) in the next post. This was a joint project of U of Oregon’s Ecosystem Workforce Program and RVCC with support from the Forest Service. The below is an excerpt of part of the paper. The whole report is worth reading, and has many other points worthy of discussion.

5. Guiding principles and recommended next steps

In this section our goal is to provide guidance to the agency for moving forward with revising performance measurements in accordance with the Shared Stewardship Strategy. Our suggestions are derived from recommendations from the literature, stakeholder feedback, and our own experiences working with the agency

5.1 Internal agency considerations to prepare for performance measure redesign

The agency must define and communicate a clear purpose and audience for new performance measures prior to moving forward. We suggest that the agency consider the following questions and recommendations before requesting input from stakeholder partners.

It would be nice if all efforts required “communicating a clear purpose and audience prior to moving forward.”

Implementing Outcome-Based Performance Measures Aligned with the Forest Service’s Shared Stewardship Strategy 13

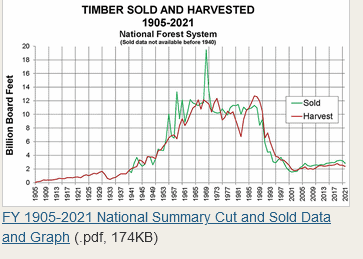

• What decisions and changes are new performance measures intended to inform? Whose behavior will change, and at what levels of the agency, as a result of the new performance measures? Be cautious of defining too many goals for performance measures. Composite priorities, such as those that are often referenced together in Shared Stewardship (e.g., cross-boundary, geographic prioritization, partnership), may require distinctly different performance measures.• Will new performance measures replace or complement existing measures? New performance measures will not exist in a vacuum independent of existing measures, particularly timber volume and fuels reduction acre targets. As noted in the literature review, easily measured and defined goals and associated performance measures are likely to crowd out those with more complexity. Furthermore, if new performance measures have no connection to budgets or staff performance reviews, they are unlikely to motivate or institutionalize new bureaucratic behavior. The distinction between performance measures should be clarified internally within the agency and externally for partners prior to moving forward.

• Who are the intended audiences (e.g., WO,Congress, OMB, states, community partners) and what would be meaningful to them? A single performance measure is unlikely to meet

the needs of all possible audiences. Counts of partnership agreements, for instance, may help signal progress to Congressional audiences, but are unlikely to be particularly meaningful to local stakeholders or state implementation partners. We encourage dialogue with intended audience(s) to ensure performance measures are meaningful to those parties.• What investments will the agency be able to make in data collection and management? Utilizing existing data may be necessary and preferable in the short term; however, new performance measures will likely require some level of new data collection. We encourage the agency to recognize that updating existing databases and creating new fields, if not whole new data systems, is likely needed to meaningfully report on partnership outcomes.

• At what scale does the agency want to implement new performance measures? The recommendations and considerations offered below apply broadly across most or all scales, but

performance measure design and implementation will look different at varying scales. For instance, the principle of inclusivity may look different if a performance measure is intended to evaluate a District or District Ranger compared to a Region or Regional Forester.We also recommend that the agency make revised performance measures one part of a broader strategy to ensure that incentives and policies within the agency align with the intent of the Shared Stewardship Strategy. In particular, we suggest the agency convene a series of workshops for academic partners and practitioners who specialize in United States public lands forest governance and policy to consider options for broader reform efforts within the agency (e.g., reforming the National Forest Management Act, incentive structures within the agency, long-term visioning). We further recommend that the agency convene a structured meeting of national partners to further develop recommendations for implementing revised performance measures.

I’d only add that partnership-ish measures at the landscape scale should perhaps be coordinated in such a way that landscapes with intermix of BLM and FS should consider collecting the same kind of information and consider developing similar performance measures in those areas, if performance measures occur at the landscape scale. I think partners, neighbors and taxpayers would thank you.