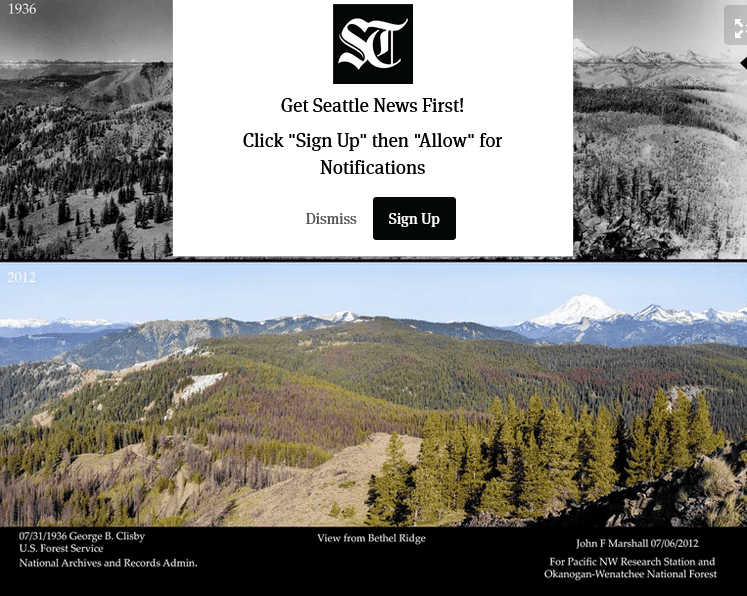

Many thanks to John for this link to a Seattle Times story on John Marshall, who is taking photographs from the same areas as the Osborne photos of the 1930s. Very cool photos and it’s not paywalled. If you want to learn more about the Osborne photos, Bob Zybach provided a link to a project trying to provide comparison photos over a broad area. The Osborne photos from some areas you may be familiar with are posted on the site. This seems like a useful effort, and it sounds like lots of different folks are funding different parts. I’m surprised someone with funds doesn’t take this on more broadly and coordinate. Here are some quotes from the story:

His images, taken from the same vantage points nearly a century later, illustrate the consequences of relentless fire suppression. Across the state, Marshall has documented the transformation of landscapes historically characterized by patchworks of saplings, mature trees, shrubs and meadows — all shaped by frequent, small fires. Today, clearings have been swallowed up. Habitat diversity has diminished, and ridges and hillsides are thick with timber. Many forests, especially in Central and Eastern Washington, are stressed by overcrowding, heat, drought and insect infestations — and primed for megafires.

It’s not a new story, but the pictures tell it in a way words can’t.

…..

Forest Service ecologist Paul Hessburg, who helped recruit Marshall to the panorama project in 2010, has used the before-and-after images in scores of scientific publications and nearly 200 presentations to peers and the public, making the case for allowing some fires to burn and deliberately setting others to reduce the risk of massive blazes.

“These visuals are so powerful because they show the scale,” says Hessburg, who’s based at the Pacific Northwest Research Station in Wenatchee. “People come up to me after talks and say, ‘You know, I wouldn’t have believed it until I saw it — but there it is.’ ”

The panoramas also helped Hessburg bust a long-standing myth that high-elevation forests in the Northwest hadn’t burned frequently in the past. “John and I have been working together in different geographies to show people how, in 100 years or less, the forest has changed,” he says. “And it’s changed more than we could have even imagined until we had these pictures.”

**********

The agency recently launched a forest health initiative that includes tree-thinning and prescribed burns. “We’ve grown up with these dense, thick forests, so people naturally think that’s what a healthy forest looks like,” says Chuck Hersey, of DNR’s Forest Resilience Division. “But our fundamental forest health problem in Eastern Washington is that there’s too many trees.” Side-by-side images separated by nine decades make the case at a glance, showing the stark changes in the landscape.

One example is Squilchuck State Park near Wenatchee, where fire used to sweep through every dozen years or so before land managers started snuffing out every blaze. A detail shot from the 1934 Osborne panorama shows open meadows interspersed with clumps of mature, fire-resistant Ponderosa pine and sparser stands of firs and other species. In the image Marshall made in 2018, the area is blanketed with wall-to-wall trees. The pictures helped Washington State Parks explain its rationale for two recent thinning operations to lower the fire risk.

*************

In 1934, several patches across the landscape had recently burned, he explains. Some were ringed with shrubs and deciduous trees. Now, most of those areas are completely knitted in with conifers. But in other places, there seem to be more openings in the tree canopy today than 90 years ago.

“That’s due to insects and disease,” Marshall says. While fires clear out flammable material, infestations don’t. “It only adds to the fuel loads, which are just ginormous now.”

We might want to email the reporter and thank her.. “catch people doing something right”.. maybe FS folks remember the training we had on that..

So, how many times do various forest landscapes need to burn to accomplish fire resilience? What are the chances for vegetation type conversions? Maintenance requirements? Feasibility of maintenance with Rx fire? Capture by non native species.

Restoration of species compositions can be very important, where shade-tolerant lodgepole pine and true fir currently populate the pine understory. Same for tree densities.

A little background before I get to answering your questions. I worked on the Wenatchee National Forest as the Forest Analyst in the late 1980’s until 1997. We were very concerned about what we saw happen in fire behavior and effects starting in 1987.

The Indians managed the dry forests of the western United States for forest products that they needed: namely food products like camas roots and habitats that supported wildlife that they could kill and eat. They used fire to maintain those habitats.

European settlement changed how the forests were managed so they could provide products needed by a European lifestyle. The big one was WOOD. America’s public lands started being managed for WOOD to build mine supports, railroads, homes, and burned for fuel, etc. etc.

That also led to the concept of “full stocking” and slowly over the decades the public and private forests moved to greater tree populations to maximize WOOD production. We didn’t need camas roots, but we wanted lots of pine molding and 2×4’s of Douglas-fir for homes.

That is until the late 1980’s when we as a society decided we were NOT going to cut trees on public land.

We would let them grow NATURALLY. Except NATURALLY was not how the forests were managed by the Indians.

We as a society did not realize that slowly we had created “EPIDEMIC of TREES” on our public forest lands. We no longer had Indian managed forests, but NO MANAGEMENT forests.

After the devastating fires that started in late July and finally ended sometime in November I returned to the office and decided to do some ForPlan runs to see how much BIO-MASS was growing every year on the Wenatchee National Forest. EVERYWHERE including Wilderness, RNA’s, spotted owl circles and other protected areas.

The harvest level pre-forest planning was 175 million board feet. The preferred forest plan was 125 million, and the Gang of Four plan, also known as Clinton’s Forest Plan the harvest level was 25 million.

Throwing all the lands that were capable of growing commercial trees into solution, resulted in an estimated growth level of 500 million board feet a year.

500 million growth versus a harvest level of 25 million.

Now multiply that by the 123 proclaimed National Forests.

You cannot harvest your way out the problem. You cannot use prescribe fire to return the Indian managed landscape.

It is a EPIDEMIC OF TREES and it will follow the biological rules for epidemics.

On the Wenatchee National Forest the Chelan Ranger District was once a leading timber producer. There were lots of mills dependent on trees from first the Chelan National Forest.

And then the fires of 1970 and earlier came and changed the landscape. Removing the trees and replacing them with brush, carpets of lodgepole pine 4 inches tall after 20 years, and the conversion from soil to base rock.

I calculated a sustain yield level for the Chelan Ranger District of 5 million board feet. The District Ranger invited me for a two day field, just him and me, so he could introduce me to ALL the trees on the Ranger District.

There was one drainage Railroad Creek that was included in the “available” timber base. It should NOT have been since there was no way that it would be harvested. It burned in a very hot fire a few years ago. It was where ForPlan was finding it 5 million board feet.

Then the 1990 fires forward occurred and currently, there are only a few forest patches left on the Ranger District. None that I would characterize as forest.

The Chelan Ranger District went from a major timber producing district, to one without forests as a result of the wildfires. The Ranger District to the south suffered a similar fate due to wildfires.

That is the future of our National Forests. Lots of areas where the soil has been totally burned off, brush fields, and carpets of small lodgepole pines at the higher elevations.

It is too late to save our National Forests. RPA 2020 data (collected in 2017) showed that net growth on the National Forests is going negative in the near future. It is already negative in the Rocky Mountain National Forests and my view is that it is negative in the National Forests of Washington, Oregon and California with the fires since 2017.

I have been talking with my classmates from UC Berkeley class of 1972 and they have commented that the large fires like the Dixie and Caldor fires have created huge areas (Dixie was almost a million acres) that have NO SEED SOURCE that survived. They will convert to brush. It will be thousands of years before they return to forests. We cannot grow enough seedling or hire enough people to plant them before the brush will totally occupy the site.

The second wave of fires will totally seal the fate of our public forests. They will be fire resilient because there will be few trees. Just widely space brush or open spots of bare rock. Invasive species have been an issue following the fires on the Chelan Ranger District and I suspect it will be the same in other areas.

In another 30 to 40 years we will have totally converted our western dry forests to a “new” landscape that will move on a new ecological trajectory.

As I noted before, history will judge the environmental movement harshly for the destruction of our public forests.

As in any EPIDEMIC we will need to practice and implement triage plans to save iconic and important landscapes like the Giant Sequoia’s in the Sierra Nevada’s. Each National Forest and Park should make a list of areas that we need to save from destruction.

At least, in Aldo’s words, we need save some of the ecological pieces to remember what we once had.

Within the footprint of the Caldor Fire, the Placerville Ranger District, on the Eldorado National Forest, was heavily managed. Almost the entire Ranger District was under a salvage plan from 1989 to 1993. There were plenty of thinning projects after that, but the Ranger District still burned. Additionally, there was maximum management on private timberlands, too.

The good news is that lots of trees did survive. However, brush grows very well there, and I doubt that the pace of reforestation will ‘out-compete’ the brush. Yes, we HAVE seen heavily-managed timberlands burn to a crisp, too. It’s more about what that management wants to accomplish, and SPI manages for logs, not for forest resilience. Also, an important factor is the lack of funding and staffing from Congress, which the political folks don’t want to address.

“As I noted before, history will judge the environmental movement harshly for the destruction of our public forests.” Where in the world did this come from? This article is about photos to “illustrate the consequences of relentless fire suppression.” I think that is more on the timber industry than the environmentalists.

The forests in the Wenatchee area are unhealthy and need active management. However, I do not need a photo from 1936 to demonstrate that and I don’t think it’s appropriate to use a photo from 1936 to make that point or develop stand or landscape prescriptions.

Why would a photo from 1936 represents the natural range of variation?

First, they are literally snapshots in time, which by definition do not represent a range. A single data point does not represent a range.

Second, one must ask and answer the question, “What effects occurred as a result of Europeans in the photographed areas before 1936?”

By the 1930s Europeans had already lived in the Wenatchee area for more than 40 years, with the railroad arriving in 1892. Millions of sheep grazed that landscape and sheep herders did a lot of burning of dense forests and shrubs to open them up to increase forage, well before those photos were taken.

By 1917 the region was producing 20% of the US apple crop. What were apple boxes made out of? Wood. Where did the wood come from?

Not to mention, what happened in the late 1600s?…small pox hit the western native american tribes, killing 90% of them before European settlers even arrived in the 1800s. The loss of 90% of the native americans had a significant effect on fire size and frequency, considering native americans were prolific burners.

What is the natural range of variation? It’s not a photo from 1936, that’s for sure.

In my view, there is no such thing as a “natural range of variation”. That is a pretty harsh statement, but ecological trajectories have always been influenced by man since the glaciers withdrew to the higher elevations and north.

We significantly underestimate the Indian management of forests in the western US. For a “natural range of variation” how do you factor in Indian management of the forests?? Do we accept Indian management as natural and European management as un-natural???

While I was working on the Wenatchee in the 1990’s we did find a paper on the east slope forests complete with maps that was published in the early 1900’s or thereabouts. The name of the author escapes me at this point. They were LOTS more burned areas than even the 1936 photos indicate. I don’t know how many of those were railroad fires if any.

I also found a report for timber stands on Sections 16 and 36 that were cruised by the state of Washington for school sections around 1915. The timber volume was very low even for the higher elevation forests. Since 16 and 36 were “randomly” tossed across the landscape, I always was tempted to do a inventory based on those samples.

1936 represents 50 years plus of in-growth into the Indian managed forests. Your right on that.

The one factor is that European trained foresters brought in was the concept of “full stocking” of the site and most foresters consider that normal and desired. That was just a figment of a society that was concerned about running out of trees and that mindset transferred to American forestry practices.

Early in my career, I worked on a couple of growth studies in California including one for Michigan-California Lumber Company. I was shocked at how fast and how quickly trees grew. So was Mich-Cal, they thought the growth study was in error since they had been liquidating their property as quickly as possible for the last 10 years and ONLY managed to harvest the growth!!!

We as a society have never progressed beyond trite slogans for managing our public forests. They range from preserve all the forests to full stocking to maximize fiber production for wood products and at different times in our history we have used those trite slogans to set forest policy.

On the Wenatchee we had mixed conifer stands totally unraveling from overstocking and disease and insect outbreaks. They were absolute fire traps. They also hosted a thriving spotted owl population. The management question thanks to ESA, was how do you keep a timber stand unraveling for the longest period of time to maximize the survival of the Spotted Owl.

We didn’t find an answer as the funding dropped off as interest in saving the Spotted Owl waned. I suspect those stands were WAY DIFFERENT than any previous forest stands. They represented a new forest ecological structure.

Let’s not confuse “historic range of variation” and “natural range of variation.” The former is fixed in time, but the latter is intended to be adjusted for foreseeable (mostly climatic) future conditions that make the historic condition less relevant. (And “range” makes it clear this is not a fixed point, like one of these photos, as implied by Anonymous above.)

Hi Jon:

I would accept what you say, but only if your definition of “natural” includes the presence of people (and fire and firewood gathering). My research through the years — including analyses of hundreds of Osborne photos — mirrors the statements of Anonymous and Vladimir.

My experience with the word “natural” is that many people seem to interpret it as an environment in which people are basically pathogens and ruin everything. People and their fires are the truly natural component of forest structures and populations that most people — and their legal representatives — don’t seem to understand.

Better sit down. I agree with you that “natural” was not a good choice of words for what the Forest Service meant when it made this into regulatory language (and I’m sure I objected at the time). As for the past (HRV), I’m ok with defining “natural” as what the current (evidently sustainable) ecosystems evolved with over millennia, including human intervention by hunter/gatherers.

As for the future, the Forest Service has to make the case that what they are planning (for vegetation conditions) will be sustainable (ecological integrity), and to the extent they can’t do that based on historic reference conditions, they must explain why they want to depart from historic conditions and they probably have a heavier burden to provide a rationale for why that would be sustainable. Reading (and writing) the Forest Service Handbook, and seeing what’s in revised forest plans so far, I believe the thinking is that historic conditions would be the best target for most parts of most national forests, and exceptions to that for some parts of some national forests would have to be justified.

Trust me, Jon, I was already sitting. I have to admit, though, I honestly have no idea what “ecological integrity” means, but I do know I have mocked previous efforts by modelers to somehow derive an “HRV” from their computer. If “historic conditions” is the “best target” for a National Forest, does that include the 1861-62 floods, 1962 Columbus Day Storm, or Mt. St. Helens from time to time? And how did the 2020 Labor Day Fires fit into existing USFS plans and projections? I do think we can do a lot better planning for the future rather than trying to emulate the past.

I am fine with your comment.

BUT if we don’t know what climatic conditions will be in the future AND how the landscapes will respond to them??

Are we not talking about how many angels on the head of pin??

Ah, the old “angels” analogy. My MS advisor (at Colorado State) used to talk about that – must be something about linear programming. We never “now the future,” but my understanding of the legal reality is that there is no level of uncertainty where the agency is entitled to throw up its hands and say we’re not going to plan – we’re just going to do the projects we want to do now.

No my point was not that we should NOT plan for uncertainty.

It was actually the exact opposite.

The ONLY sane thing the Forest Service did in its planning process was the attempt to define desired future condition. That introduced a element of certainty and more importantly the activities necessary to achieve the “desired future condition”.

The Forest Service never understand how important the concept of desired future condition was in planning.

If they had focused on that, they might have actually come up with a Forest Plan that served the American people.

It would have been interesting if the Forest Service focused on desired future condition and asked the public (including environmental groups for their definition and the techniques to achieve the DFC). It would have been an honest discussion.

In the immortal words of Ian Tyson “ah, but wishing don’t make it so”.

Forest Service planning was an exercise in wishing and that is why is failed so spectacularly.

In fact, this was maybe the key premise behind the 2012 Planning Rule – put specific desired conditions in the forest plan instead of developing them project by project. I think this is happening to a degree in revised forest plans, but typically not going much beyond forest overstory tree species/age. Less clear was whether there is a need to consider alternative desired conditions, given that they are supposed to be based on the natural range of variation. I don’t think I’ve seen that done.

John Marshall added this link to more photos..

“If you want to see more of my Osborne Panorama comparisons, check out this website that my son Charles built. Not all that I have done are on there.

Osborne-panoramas.org”.

Wow! Charles is doing a great job! And undoubtedly a good time doing it. I posted this somewhere else, but here is the Osbornes Project I’ve been working on (and mostly off) for several years and better situated in this discussion: http://www.orww.org/Osbornes_Project/index.html

Is there a reason the link doesn’t work on your post? Quote mark? Software? The URL works fine when I type it in: https://www.osborne-panoramas.org

I am adding this comment from David Chojnacky who is not on the forum: This has been shown over and over by many photographers. However one missing piece in the comparison discussion is: most (if not all) U.S. landscapes were managed with fire by indigenous peoples for centuries prior to late 1800s. What were landscapes like prior to indigenous peoples? Perhaps 21st century post-megafire landscapes are returning to what they were prior to indigenous peoples. If other words, one cannot just assume 1930s landscapes were some magical norm that should be achieved. Forestry is filled with myth based on rash conclusion and this seems a huge one!

This book should be required reading for EVERYBODY that is involved in natural resource management.

https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520286009/the-west-without-water

It is almost entirely focused on California, but it has a ton of references that talk about species composition and major climatic events during the last two thousand years primarily.

I am not sure that your statement “What were landscapes like prior to indigenous peoples? ” is relevant simply because many of them were they were covered by glaciers. I do have a close friend that is a Great Basin archeologist with lots of experience in California and Pacific Northwest and I will have to ask him the question. Not sure that per-glaciation is within the natural range of variability.

I totally agree with your point that 1930’s landscapes are NOT a magical norm. We need to choose the desired landscapes just like the Indians did.

In fairness, to Hessburg and others, they don’t believe in a “magical” landscape. Their focus is on fire resilient landscapes.

The post-megafire landscapes are not returning the landscape to a prior condition.

The fire severity has literally evaporated the soils in lower elevation landscapes in some cases. The large area covered by mega-fires and the resultant removal of seed sources insures that in parts of the dry forests we will literally have brush fields for centuries.

My guess is that we have another 30 to 40 years where we will burn over the forests for a second time thus sealing their fate for centuries. Then we will have a fire resilient landscape.

Here is the fire history since 2000. It is missing the significant fires that occurred between 1985 and 2000 like Yellowstone, Tyee, etc. Scroll around the map. It is sobering.

Landscapes covered with brush and grass are not fire resilient. In fact these landscapes tend to carry intense fire faster and are more resistant to control due to high ignition probability of spot fires and ember cast than forest types.

You have a good point.

But brush fires in what use to be forests I suspect tend to behave differently than fire dependent brush eco-systems.

In Lake Chelan, we had fire after fire and finally eliminated the trees. Then the Wolverine Fire exploded in the last remaining last forest stand and headed south. It stopped when it hit the brushfields that took over former forest lands.

Plus there is much less BIO-MASS in brushfields. And the crown fires, well the crowns are much, much lower to the ground.

Anyway, on the edge here and will defer to those with a better fire background.

That probably is the key component.

Roger:

Yep. After the snags are finally eliminated through multiple fires, brush and grasses take over that burn even more often and more rapidly. Check Australia for a current example. The people who are claiming “science” shows the forests becoming “more fire resilient” through these events are either nitwits (for going public with their nonsense) or scam artists making an income by scaring people (“funding sources”) with their “authority” — and greatly undermining the credibility, practice, and teaching of actual science in the process.

These fires are bad for other people, for our forests, for the air, and for our wildlife, yet no one seems serious about fixing the problem. Salvage logging, site preparation, and informed reforestation and forest management practices are the solution, but politicians, the media, and science grifters are happy with the current situation and have kept this lucrative scam going for far too long, in my opinion.

I have read through all of the comments in response to the article in the Seattle Times and will make a few of my own. The relevance of 1930s photos is being critisized. Yes, I wish that we had a good set of panoramic photos from 1855 when the Indians were run off the land and put on reservations, but we don’t. Even if we did, that would be inadequate, as 90% of the native population had died before 1800 due to introduced diseases. If someone will come up with a comprehensive set of photographs of Pacific NW forests from the 1790s, I will abandon the Osborne Panoramas. Until then I am sticking with the Osbornes! It is the best thing we have to get through to the environmental crowd that landscapes packed with trees wall to wall was not the norm historically, and is not the desired condition now.

The Seattle Times article should be seen as an eye-opener and conversation starter for everyone. It is not comprehensive in covering every aspect of history and landscape ecology, nor should it be. If you report too many details, you won’t gain an audience.

In the entry to his book “Playing God in Yellowstone”, Alston Chase quoted G. K. Chesterton.

“All conservatism is based upon the idea that if you leave things alone you leave them as they are. But you do not. If you leave a thing alone you leave it to a torrent of change.”

Predicting how that change will occur and what the end result may be is extremely difficult with all the variables involved.

When we see problems and negative trends developing we need to stop and reevaluate. So far politics, opportunist, and money are keeping us from doing that.

John, thank you for responding and thank you for doing the Osborne work. Anytime you do something, it seems to me, there will be critics. You didn’t do it the right way, or you didn’t do enough, or… As Teddy Roosevelt said..

“It behooves every man to remember that the work of the critic is of altogether secondary importance, and that, in the end, progress is accomplished by the man who does things.”

Sharon- Thank You! Well Said!

Hi John: In addition to Osbornes and aerial photos — which often precede Osbornes — one of the best tools I have used to research past forest conditions is General Land Office survey notes, which do go back to to 1855 in the Willamette Valley and a few other locations. The same is true for early explorer journals, which are not so precise, but offer good insights going back to Lewis and Clark and even earlier along the coast — and certainly much earlier east of the Rockies.

As you say, significant mortality occurred in most western US Tribes before 1800, and there is good evidence that deadly introduced diseases may have traveled throughout most of North America even before the 1600s. The value of adding GLO notes — which have been transcribed from cursive field notes to very helpful typewritten copies in many counties by Daughters of the American Revolution in the 1930s — is that they have the distances between tree species (“Bearing Trees”) with diameters, meaning that ages can be inferred or determined with coring, and spacing is systematically documented in a predetermined grid pattern. Also, descriptions of the environment are included that often include identification of shrubs, meadows, and prairies and even the names of landowners, squatters, and their homes and gardens in many instances.

This information can often be used to approximate vegetation conditions going back dozens or hundreds of years earlier, depending mostly on tree species, age, and density. The Osbornes are a wonderful tool, but even more powerful when combined with other sources of evidence. Here is one example of research I did on the headwaters of the South Umpqua in western Oregon a little over 10 years ago: http://www.orww.org/Osbornes_Project/Rivers/Umpqua/South/Upper_Headwaters_Project/ca_1800_Forest_Zones/index.html

Interesting Bob! I am curious where your ethnographic information comes from? Did you interview tribal members. I have heard that the quality of work in the GLO surveys varies. I am currently looking into the Barlow Trail around Mt. Hood. I have found an excellent account by Joe Palmer written in the 1850s. I keep circling back to the idea that pioneers had a relatively easy time of it getting over mountain ranges on account of Indian burning that preceeded them. I say “relative”, it was still hard, but without Indian burning it would have been impossible.

Hi Anonymous: I have been hired to do research for a number of Tribes over the years, including an oral history interview project regarding lamprey eel fishing for the Siletz in the 1990s, but most of the landscape history information comes from early accounts mostly written by white guys as journalists and surveyors. That is primarily because Tribes spoke different languages — ones that didn’t have written languages — and most people were illiterate during those times. This was particularly true for Tribal members and most women.

Yes, there are differences in quality between different GLO surveys, and some were even purposefully misleading, but almost all of them are very useful for these purposes. Ground-truthing and familiarity with the landscape are key to making more precise interpretations. Buttressed by historical photos, maps, and research, of course. Most of the people I have met who have dismissed these sources for that reason is because they aren’t very familiar with them and prefer conducting easier research, while still trying to retain authority on the topic. Sad but true.

I’m pleased you are interested in the Barlow Trail. I was just in Wamic recently discussing that route with a local businessman and have done extensive research on the 1845 crossing. My focus was on the experiences of Letitia Carson, a Black woman who gave birth along the way and didn’t take the Barlow cut-off. The Palmer account is great, and a glacier has been named after him for that reason. And also because of his other accomplishments. If you are not a member of the Oregon-California Trails Association, I highly recommend joining — I think they’re even doing a special Barlow Trail research project at this time that is being videotaped.

The main advantage of the Indian burning practices to earlier travelers was because it provided forage for their oxen and horses, and fairly abundant wild game for the humans. Mountains were tough in spots in large part because of the lack of forage — the Rockies were made passable largely because of Jedediah Smith’s rediscovery of South Pass, and subsequent mapping and promotion of the route to national leaders.

Bob- This is John Marshall. I did not intend to be anonymous with my comments about the GLO and the Barlow Trail. I did not realize that on this forum one has to actively fill in their name.

Thanks John: I’ve made that mistake a few times, too — and there’s no way to correct that I’ve seen.

Bob- To continue the discussion, I am fascinated with the nexus of Indian burning and pioneer experience, and what it tells us that we should know today. The Osborne Panoramas are just one point on a continum of an expanding forest footprint with greater density. We are in a difficult time where if our forests are to survive we need gaps and openings, less density over all, and a shift toward retaining larger trees among the more drought and fire tolerant species. Making people understand this and how we might implement the needed change is my agenda.

Total agreement. The ridgelines and stream sides used to be open and largely fuel-free because that’s where people went and where they traveled for thousands of years. Now we have contiguous crowns due to planting, seeding, and federal regulations — and the predictable wildfires follow.

luckily you are anonymous in the vein of Bob’s agenda so I bet he’ll respond favorably to you instead of discounting you.

It’s not a “luck” thing, Anon. It’s called “good manners.” People such as yourself who hide behind a fake identity in order to publicly call known others names or belittle their credentials are cowardly jerks or just irritating trolls at best. You should know that.

It’s only a volunteer job without pay, but when those types of folks — looking at you, Anon — start cluttering up a discussion with their dumb distractions, the Hall Monitor badge comes out. It’s a dirty job, but somebody needs to do it.

Apparently it’s necessary for some to use a pseudonym and other times it’s accidental, but good manners and reasonable comments are the hallmarks of a welcome Unknown. No reason to be rude, and not too many to be hidden.