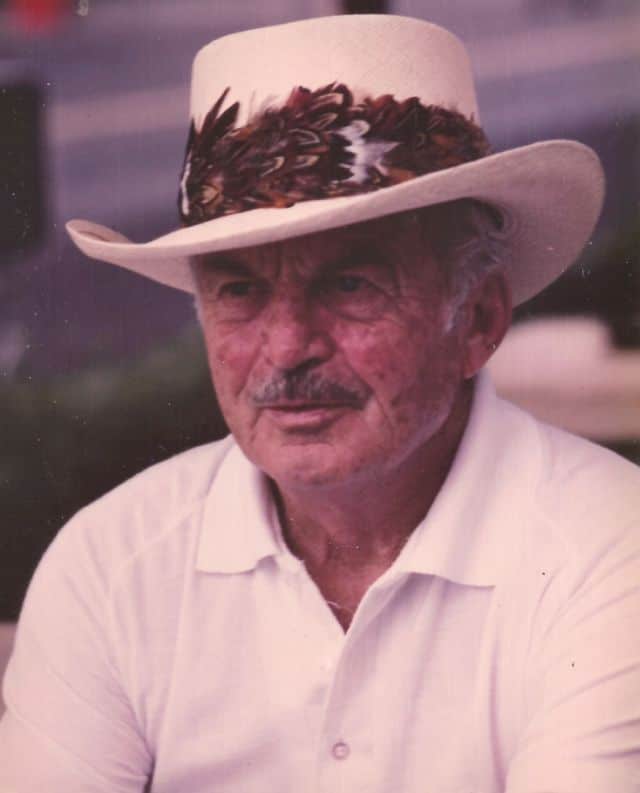

From Bill Bentley (this is from the Forest Service stories collection from 1990-ish). Here’s the timeframe perspective from Bill:

I think he retired in 1969 or early 1970 after 37 years with the Forest Service. I had just moved to Ann Arbor. Unless my memory is off, he joined the old USFS California Forest & Range Experiment Station in late 1932.

A son has difficulty writing about his father, especially if they were close. Dad and I became best of friends as I moved into my middle years. Dad’s intense interest in what he was doing professionally put me off as a kid, but eventually inspired me to follow in his footsteps with a career in resource management and conservation.

The first time I really identified the seriousness of Dad and his Forest Service colleagues we were together on a field trip out of Porterville. I had just finished my freshman year, and joined Dad on a Range Society tour of range rehabilitation and management on the Sequoia National Forest. Dad, Ralph Fenner, some other fellows, and me came in from the field, hot and dusty, about 7:00 p.m. We then began a long review of the day, the use of fire in forest and range management, and the impact of low cattle prices. About 10:30, one college freshman who was floating on the ceiling began to complain. All this talk and no mention of girls, baseball, or politics and he was very hungry! The men laughed and apologized for not getting on to dinner sooner, then went back to their debate.

How Jay Bentley got to California is an interesting story in itself. He was working on a master’s in soils and agronomy at Kansas State. It was a cold November day, and he was near the campus digging out a Lesbadezia [sp?] shrub to trace its root patterns. His roommate, Don Cornelius, peered over the top of the hole. “Jay, you just got a telegram from California. The Forest Service will pay you $2,600 a year if you’ll report right away.” Dad, in recalling this story, said as far as he knows the shovel is still in the bottom of that pit.

By the time I was a forestry student, Dad was with Operation Fuelbreak. He was working more and more closely with the Regional Office in San Francisco and several national forests. Once Eamor Nord and I were in a ranger station near Walker Pass. When the ranger heard my name, he asked if I was related to Jay. “Yes,” I said, with some pride but concern for what came next. Growing up in your Dad’s shadow is not always a comfortable process. “Well,” responded the ranger, “it’s always a pleasure to work with Jay. He understands our problems, and helps us solve them. A real unusual experience, in my opinion, working with researchers.” That’s a story I still use in workshops on applied research here and overseas.

Dad moved more and more into research useful to the National Forest System. The range rehabilitation work shifted toward brush conversion for timber management as he moved to the Shasta Trinity and northern Sierra national forests. I followed this work on periodic visits as a graduate student then young faculty member. He, his crew of young professionals like Tim Plum and Ken Brigeman, and their national forest counterparts were working through a complex of ecological, managerial, and other factors which were good grist for my learning processes.

One Sunday afternoon, we were exploring the cost and returns from brushland conversion while barbecuing a piece of well marinated beef in the backyard. It became obvious as the conversation went on that we had different perspectives on the subject. Finally, in some exasperation, he turned to me, the budding forest economist, and said, “Say, you’re not one of those ‘SOBs’ who believes in compound interest, are you?”

Interestingly enough, that conversation led into a much more profound and continuing dialogue about the management of vegetation and related land-based resources. Dad and his team were trying to speed up natural successional patterns using fire, herbicides, seed, seedlings, fertilizer, and other inputs. But what they really were trying to do was use managerial control to guide nature toward a vision of what the landscape could look like and produce. Their visions were not intense systems, but ones that worked to produce more range forage, timber, and other multiple uses. Their philosophy was, “Learn how to do it right first, then worry about reducing the costs.” It took me some time to understand the importance of this philosophy, but once it stuck I have been alert to the many times resource managers focus on costs then lose their investments to the risks of nature’s complex response to our managerial schemes. Whether you’re managing timber and grass for money, for wilderness, or for watershed protection, you have to start by doing it right.

In the 1960’s, Dad and several other Forest Service researchers put their skills to service in Vietnam. Their activities were controversial, and we had several tense discussions within the family. It was not a happy period for the country, and the Bentleys were a small microcosm of a national debate. In the end, however, we all learned. Perhaps we learned from each others’ positions, but mostly we learned tolerance for perspective, individual values, and humanness. For Dad and I, that gave us the basis for a true and lasting friendship.

My version of the Jay Bentley story is not necessarily the same as the story remembered by his co workers in the Pacific Southwest Station. It is a story of a son who learned from his father, often while together puzzling out some problem, and in the process learned the meaning of true friendship and human relationships. This has little to do directly with research accomplishments, but a lot to do with why they are important.

William R. Bentley

Granby, Connecticut

May 6, 1991