I am not a fan of watching Congressional Hearings because there are many people quite full of themselves with various axes to grind, who waste our time blathering on about unrelated things or giving political speeches about why the other party is bad. It would be more fun if the videos had a chat function and we could throw virtual flags on things like “unnecessary pontificating” and “completely off the topic of this hearing”. Of course, both sides do it. Congresswoman Kamlager-Dove, from LA (my native district) was filling in for Joe Neguse (from Boulder, Colorado) as the ranking member. She’s in her first term. On the House Natural Resources Committee. From LA. If I were Joe, I would ask Congressfolk with skin in the national forest game or some knowledge thereof to fill in for him at a hearing like this.. but that’s just me.

Anyway, I watched this one in March and picked out some interesting wonkish parts for you.

It’s fun to watch Representative Kamlager-Dove (with a unique pronunciation of “salmon”) grill (so to speak) Chris French on Cottonwood. Starts at 1:50:32. It did make me wonder whether short timeframes (11 days) in the Sierra for reconsultation might have to do with pressure from important Congressfolk in California? Anyway, Rep. Kamlager-Dove cuts Chris off before he has time to explain his views.

Chris also says that at a recent Regional Forester meeting, Cottonwood was thought to be a #1 problem, and also something like “every little thing that diverts natural resource biologists and others holds up implementation of wildfire risk reduction projects.”

At about 2:05:56 Susan Jane makes some statements about Plans making final decisions “binding decisions in plan level documents.” “Off-road vehicle use is authorized in forest plan with no further authorization.” 2:06:21. I thought OHV use was authorized in “travel management” decisions, which tend to be separate from forest plans. For example, the PSICC has a travel management decision we’ve discussed previously, but its forest plan is from 1984.. after doing the travel management plan would they have to reconsult on the forest plan? How is winter travel different from summer travel? If there are final decisions made in plans, wouldn’t it be better to strip plans of final decisions so you wouldn’t have to reconsult on them all the time? Oil and gas leasing availability decisions, travel management decisions, and so on seem to do just fine outside the forest planning process. It seems like they’re done when they’re needed (or forced to via litigation) not on some plan revision timeline which may put a given forest 10 or more years out.

********************************

Here’s a blog post from PERC that summarizes some of Cottonwood:

This week, multiple forest management bills passed out of committee in the U.S. House and Senate with bipartisan support. One of the bills passed by both chambers offers a permanent fix to a controversial Ninth Circuit Court ruling known as Cottonwood. This tiny provision carries huge implications for conservation, impacting the speed at which the Forest Service can mitigate the wildfire crisis and restore healthy forests.

What is Cottonwood?

The ruling requires the Forest Service to halt forest restoration projects throughout a forest whenever a new species is listed, critical habitat is designated, or other new information is discovered about a species in that forest. The projects can’t proceed until the Service consults with the Fish and Wildlife Service over whether to change its overarching forest plans, a slow and expensive process.

Pausing projects to protect vulnerable species may sound reasonable, but the reality is that this is a duplicative and distracting process. The Service already analyzes this new information before proceeding with specific projects, ensuring that no harm can come to species. The additional plan-level analysis is a duplicative bureaucratic obstacle.

And the pause itself is no small matter.

Consider the case of the Bozeman Municipal Watershed Project in PERC’s headquarters in Bozeman, Montana. The project was intended to create critical fire breaks and insulate Bozeman’s watershed from wildfire risk, but the urgently needed restoration work was delayed by 18 years. Once one suit filed under the Cottonwood precedent was resolved, another would be put forth, creating delay after delay and leaving Bozeman’s drinking water vulnerable to a wildfire.

Such examples explain why the Obama administration said the Cottonwood ruling would “cripple” the Forest Service.

How can this hurdle be addressed?

A temporary legislative fix was put in place in 2018, but it expired in March 2023. With Cottonwood left unchecked, Forest Service Deputy Chief Chris French estimates projects could grind to a halt in 87 forest plans across the West. According to French, completing duplicative analysis for all of these forest plans would take “somewhere between 5 and 10 years and tens of millions of dollars.” With an 80-million-acre forest restoration backlog, that’s time and money the Forest Service does not have.

That’s why this bipartisan congressional action is so welcome. It’s past time Congress establishes a permanent fix for Cottonwood.

“Wildfires move fast, and they don’t wait around for bureaucracy that’s slow,” notes PERC CEO Brian Yablonski. “The bipartisan Cottonwood fix will foster more resilient forests, nurture healthy wildlife habitat, and play a critical role in tackling the wildfire crisis. With larger, hotter wildfires fueled by a backlog of forest restoration projects, it’s critical we remove needless and redundant obstacles to this urgent conservation work.”

PERC stands with other conservationists in thanking Sen. Steve Daines (R-MT) and Chairman Joe Manchin (D-WV) in the Senate and Chairman Bruce Westerman (R-AR) and Rep. Matt Rosendale (R-MT) in the House for their leadership in protecting our forests.

What happens next?

Now that the bills have committee approval, they move forward for votes by the entire House of Representatives and Senate, after which they go to the President for his signature.

PERC will continue to support this bipartisan effort and move us farther down the path to fixing America’s forests.

***********************************

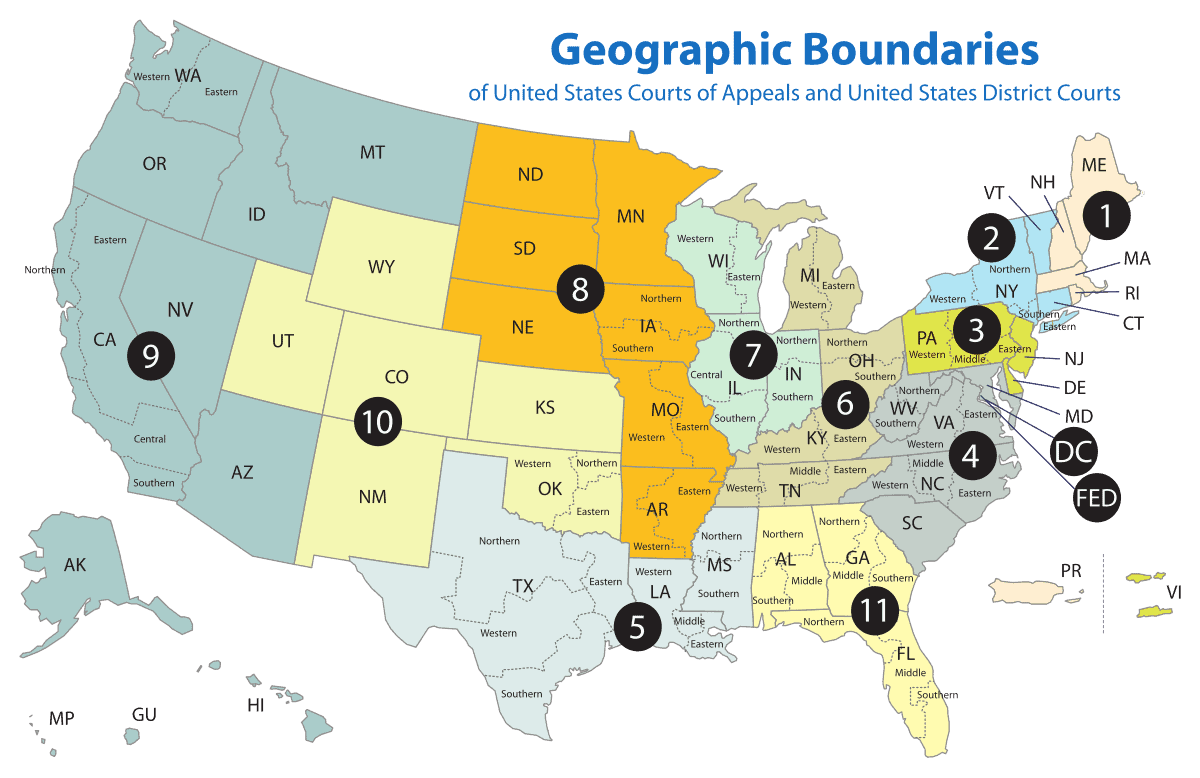

The FS testimony for the above hearing includes the fact that the two circuits disagree. Since I live in 10th circuit territory, I thought that that was worth mentioning.

The pair of Ninth Circuit court decisions, commonly referred to as Pacific Rivers Council (PRC) and Cottonwood, which held that a new ESA listing of a species or critical habitat designation required the Forest Service to reinitiate consultation on approved land management plans because either the plan was an “ongoing action” (PRC) or because the agency retains discretion to authorize site–specific projects governed by the land management plan (LMP) (Cottonwood), have no basis in the ESA or its implementing regulations. LMPs provide general management direction for an entire national forest or grassland. This direction is then integrated into projects, which normally requires a second decision and ESA consultation to dictate what on–the–ground actions can be taken. A Tenth Circuit decision (commonly known as Forsgren) reached a different conclusion than the Ninth Circuit’s conclusions in Cottonwood, and instead held that the Forest Service did not need to reinitiate consultation on an approved plan with the Services because LMPs are neither ongoing nor self–executing actions for purposes of the ESA.

I don’t know why we would assume that the 9th Circuit is right and the 10th Circuit is wrong. In case you’re curious,there are many National Forests outside the 9th Circuit.

I have seen many species listed that would certainly trigger a “may affect” determination that did not have a consultation completed for more than year, and nothing affecting the species, including actions that result in harm and mortality, were stopped. Whitebark pine is the latest on the list. I’ve seen one NOI for failure to consult, but all of the other projects that have been contracted are moving forward as planned. I have not experienced a listing that has caused any actions to stop, but I am sure there are examples.

Does anyone have an example of a pre-cottonwood listing that resulted in all activities that may affect the listed species being stopped until the consultation was completed?

Curious as to what projects are ongoing that might harm WBP?

Ski resort maintenance, timber harvest in mixed stands (kill seedlings and saplings, damage to mature trees), hazard tree removal, powerline ROW maintenance, prescribed fire…

No, these are not actions that jeopardize the species, but these actions cause mortality and some result in loss of habitat (i.e., adverse effects, requiring section 7 consultation).

How were the forests managed for the previous 60 million years, before we invented the 9th circuit court?

PERC (and maybe Congress?): “The projects can’t proceed until the Service consults with the Fish and Wildlife Service over whether to change its overarching forest plans, a slow and expensive process.” This is incorrect. Projects may proceed after conducting an ESA §7(d) analysis and determining that the project would not foreclose options needed to comply with the substantive requirements of ESA in the forest plan (which should be pretty easy to show based on most project-level effects analysis). Only those projects with serious concerns should be held up very long.

The 10th Circuit Forsgren opinion questionably applied the Supreme Court reasoning for no additional forest plan NEPA to ESA consultation requirements – an entirely different statutory framework. (I think the 9th Circuit Cottonwood decision then specifically rejected the 10th Circuit approach.)

With the Forest Service (10+ years ago), I kept watching for what happened to projects when new species were listed or new critical habitat designated, whether forest plan consultation was reinitiated or projects delayed because of that. I saw next to nothing. I don’t think a lot of field-level employees in either agency knew about these court cases and the agencies didn’t promote this as policy. So other than the high profile, wide-ranging species worst case examples (where the public may have brought it to their attention), I think it was largely ignored. (I’d still be interested in seeing examples.)